Human impact on the landscape isn’t all bad – especially if you’re a swallow, a shrike or a stork.

In the olden days, I always spent a week or so of the migration season on the Shetland island of Out Skerries. There were no trees, no hedges and no electricity, which meant, of course, that there were no telegraph poles or wires.

It was a virtually perchless zone, with small birds having to make do with drystone walls and a few crofters’ roofs

Place your bets

Then one day an underwater cable brought electricity from the mainland and up went the poles and the powerlines. A few of the islanders protested, though most were pleased. I was excited, as I anticipated which species would be the first onto the wires.

I predicted a wheatear, or a meadow pipit. So I was thrilled when it turned out to be a cuckoo, a bird that is heard but rarely seen – unless it is perched out in the open.

What would birds do without wires? Most artificial perches have their natural equivalent. A TV aerial is an iron treetop, a chimney a brick stump and a drystone wall a rock hedge.

But where in nature can you find a long horizontal cable, thin enough to grip and offering an unimpeded view, providing safety from predators and a look-out for prey?

I’m not sure it exists, but is there any image more iconic of migration than newly arrived or ready-to-depart swallows sitting on wires like musical notes on a stave or pegs on a washing line?

'Perch and pounce'

Poles and powerlines are also favoured by the ‘perch and pounce’ predators such as shrikes and kestrels, while peregrines and buzzards pose on posts from which they suddenly launch themselves skywards, or downwards onto a rambling rodent.

The most regal raptors claim the most majestic thrones. There is an area in Israel where a forest of giant pylons constitutes one of the grossest blots on the landscape you could find, but it is one of the world’s best places to see large falcons and eagles.

Poles and pylons also provide nest sites for a few species such as ospreys, storks, weavers and woodpeckers (as long as the pole is wooden, not steel), while monk parakeets build a ramshackle colonial nest the size of a small car and are capable of plunging a whole neighbourhood into darkness.

At risk of being 'zapped'

For most birds, it’s safe to sit on powerlines as long as they don’t touch another wire or the ground. However, the larger the wingspan, the greater the risk of double contact and electrocution, a fate to which many raptors succumb.

But the species most at risk from powerlines are geese and swans, which sometimes fly into pylons.

Call them eyesores or obstacles, I’m willing to bet that most birds (and therefore birders) are grateful for their existence. But here are a couple of challenges for you.

First, what is the least likely bird you have ever seen perched on a wire, holding steady for at least a minute? Mine was a curlew.

Second, how many species have you counted on a wire between two poles at any one time?

My best total was in Portugal last August. Bee-eater, woodchat shrike, southern grey shrike, hoopoe, roller, red-rumped swallow and azure-winged magpie. Oh, plus a little owl on the post. Electric!

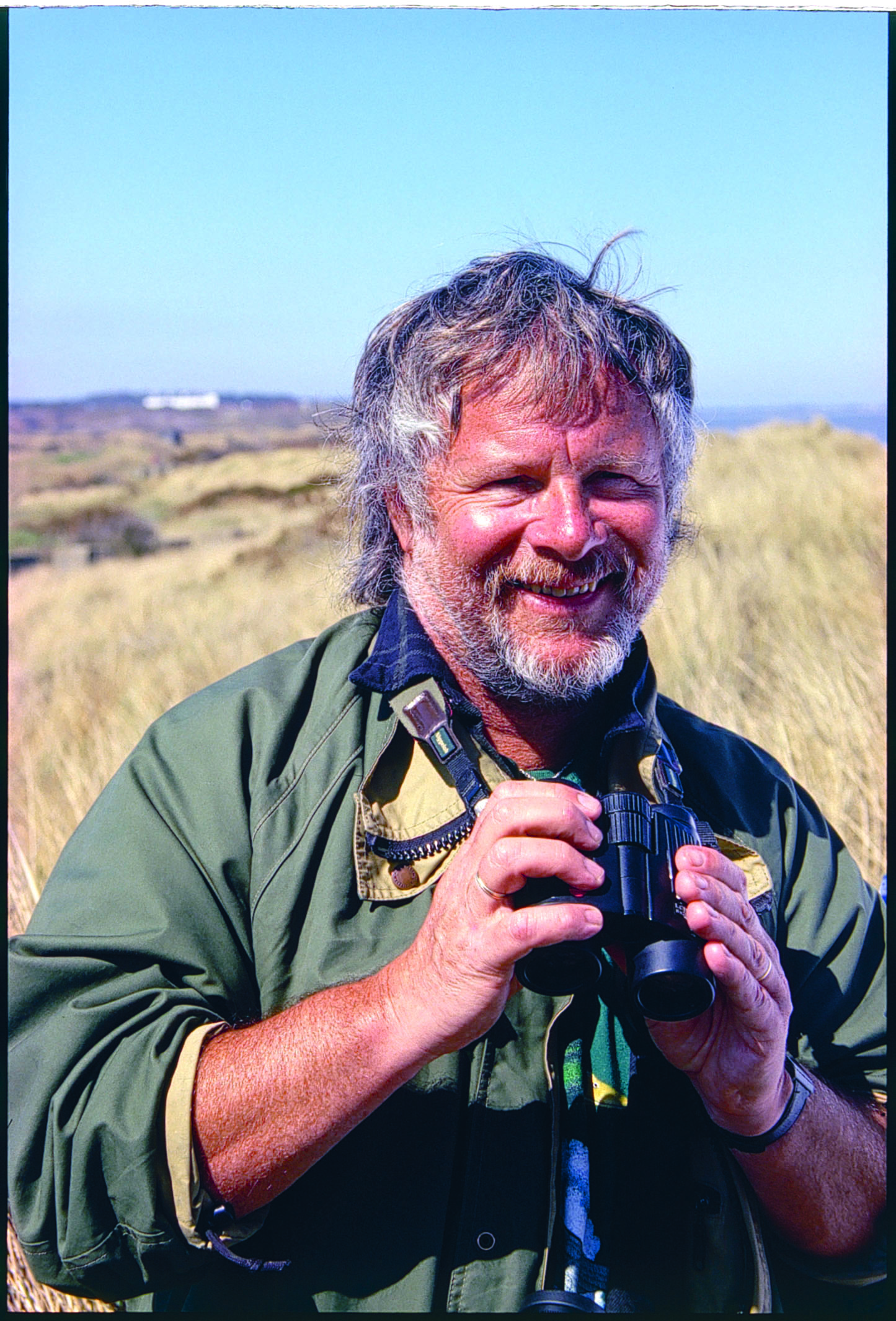

Former Goodie Bill Oddie, OBE has presented natural-history programmes for the BBC for well over 10 years, some of them serious and some of them silly. This column is a bit of both.