When a young female lynx escaped from Borth Wild Animal Kingdom in Mid Wales in late October 2017, nobody could have foreseen the scale of the outrage that was unleashed. First, it was the turn of local farmers when the carcasses of seven sheep were found in a field, suggesting Lillith had used her new-found freedom to practise her hunting skills.

Post mortems revealed the sheep had been killed by a single bite to the neck. Two had been partially eaten, but the other five were otherwise untouched, all suggesting a lynx - rather than feral dogs, as had also been mooted - was the culprit, claims the National Sheep Association (NSA).

"There cannot be a clearer warning of the damage lynx could do if they were released into the wild," says Phil Stocker, chief executive of the NSA, an organisation resolutely opposed to lynx reintroduction in any area of the UK. Lillith, it seems, had unwittingly scored an own goal, putting back the case for the reintroduction of her own species into the wild.

Are lynx a danger to sheep?

After Borth zoo spent two weeks trying and failing to recapture Lillith, council officials decided she had to be destroyed because of the danger she posed to the public, which was described as having "increased to severe" after she took up residence in a caravan park. When this was carried out there was a backlash, especially on social media.

"Since the disgraceful slaughter of poor Lillith, lynx are back in the news," reads one Facebook post. "Please support these guys to bring this beautiful cat back to the UK."

By "these guys", the poster was referring to the Lynx UK Trust, which currently has an application being considered by Natural England to reintroduce six lynx into Kielder Forest in Northumberland. The Trust's Paul O'Donoghue believes the outcry over Lillith's death has boosted its case for bringing the species back to Britain.

"People are aware that lynx are not big cats and are disgusted the council took the decision to kill this animal," he says. "It has been inexperienced, poorly advised and out-of-step [with public opinion] in dealing with this issue."

O'Donoghue maintains there was no evidence the sheep were the victims of a lynx attack, suggesting that for a single animal "to have killed seven sheep in one night is biologically unprecedented".

Indeed, the Lynx UK Trust has consistently maintained that lynx are not a threat to livestock, saying evidence from mainland Europe suggests a single animal takes, on average, 0.4 sheep a year.

"For our six lynx, that's 2.4 sheep a year," O'Donoghue says. "No one can argue that's a significant threat, particularly compared with background mortality rates."

Serial killers

But John Linnell, a lynx expert who works for the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, says lynx are capable of "multiple killings" and could dispatch large numbers without eating them. His study of radio-collared lynx in northern Norway revealed one case of eight sheep being killed by one animal in a single incident.

Lynx can also be major predators of sheep over a prolonged period. A separate study, carried out in the south of Norway, found (during the summer) sheep represented 64 per cent of ungulates killed by 24 lynx monitored over a five-year period. (Ungulates - sheep, goats, moose, red deer, roe deer and reindeer - represented 80 per cent of their kills, with beavers, hares, squirrels, foxes and grouse and other birds the other 20 per cent.) Males and females with kittens were more likely to target sheep. One individual was responsible for 54 kills in a 100-day perod.

"Whether this lynx really killed those sheep [in Wales] is not the main issue," Linnell adds. "What is important is that seven sheep were found dead, and somebody believes they were killed by a lynx. If lynx are reintroduced to the UK, this type of event will be repeated again and again within a radius of hundreds of kilometres of the release site."

These incidents will need to be responded to rapidly, and will require trained staff who can differentiate lynx kills from other predator kills and then communicate their findings to sheep farmers, the media and the public. "Who will do this?" he asks. "Who has the necessary funding, trust, skills and networks?"

There's also no question, he adds, a zoo animal could have been responsible. They were used in a reintroduction in the Harz Mountains in Germany, and "learned to kill very fast".

Tourism concern

According to NSA press officer Hannah Park, reintroducing lynx to Kielder would have a detrimental impact because of the fear of losing livestock to them.

Farmers would move away from sheep, leading to a loss, or degradation, of the environment that attracts tourists to the area. The NSA is sceptical of the line that lynx can aid tourism because they are so elusive.

"There's only so many times people will go to an area to look for an animal they cannot see," she says.

Many conservationists will cheer the prospect of landscapes with fewer sheep. Of all livestock, they arguably have the most detrimental effect on biodiversity, partly because of the density with which they are farmed and partly because of the way they feed, closely cropping the sward, leaving little variation in plant life.

But the Scottish Wildlife Trust, which supports bringing lynx back to Scotland, does not use this to justify its stance. Instead, it argues there is both a "moral and ecological imperative for reintroducing [lost] species" because they can be a cost-effective way of managing ecosystems and increasing their robustness. Not all predators would be suitable - there is appropriate habitat for lynx, the Trust argues, but not for wolves or bears. Lynx would have a beneficial impact by reducing roe deer numbers, thereby helping tree and scrub regeneration.

The Trust's director of conservation, Susan Davies, says she hopes to see a licence application put forward within the next 10 years, probably from a coalition of organisations that includes landowners and communities, as well as environmental groups.

Fake news

"I don't think [the escape and subsequent shooting of Lillith] has set reintroduction back," she says. "It shows just how much work needs to be done in terms of increasing understanding and building consensus. A lot of misinformation [came out] about what lynx can and will do."

Whatever happens with the Lynx UK Trust's Kielder application - and the word is that environment secretary Michael Gove supports the idea of doing a trial lynx reintroduction somewhere - even some conservationists believe releases of these large carnivores should not be a priority in Britain right now.

"I don't think, despite the hype, we are ready for lynx," says Derek Gow, who has been at the forefront of bringing beavers back to Britain. "There is no evidence that the Lynx Trust has built any bridges with anyone else, and a complete climate of opposition to the organisation's approach to this application - though not its principal aims - currently exists. There is support in the north from tourist-based businesses for the Kielder proposal, but a unanimous lack of support from even the reasonable elements of the farming community."

Besides, Gow adds, there's a far more interesting reintroduction idea he'd like to get involved with - bringing wildcats back to England. But that's another story ...

Lynx: global range and numbers

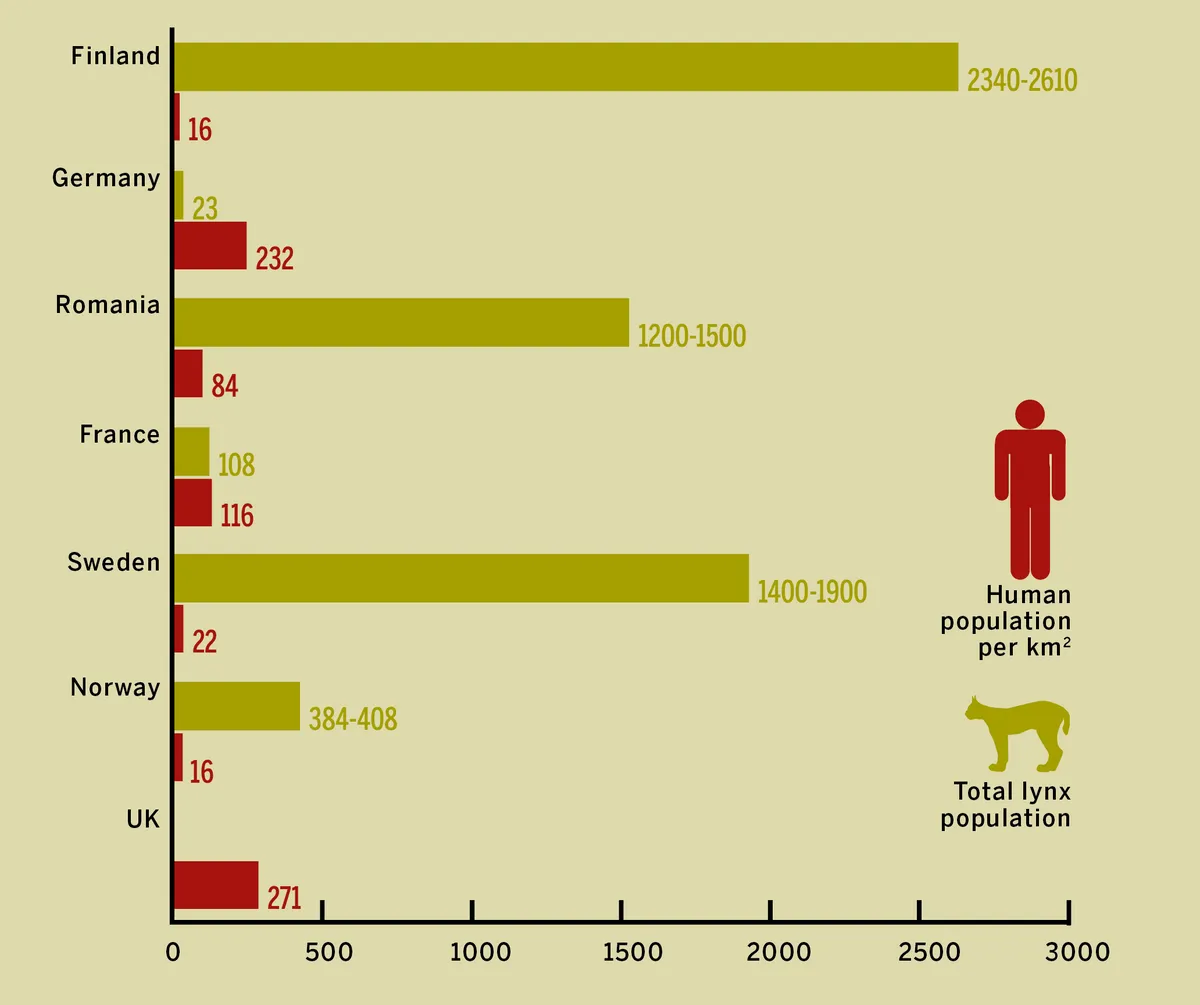

In general, the lower the human population density in the country, the healthier the lynx population. Finland has the lowest number of people per km2 of any EU country and the highest number of lynx.

Germany has a high population density and only a small, reintroduced lynx population. There are exceptions - Noway doesn't have many lynx despite being sparsely populated.

The UK has the highest population density of any EU country and - as yet - no wild lynx.