If you search the floor of a woodland hard enough, you can find a fungal palette to rival any springtime floral display, particularly in autumn. We’ve chosen a range of fungi to reflect form as well as colour, from the prince – a majestic woodland mushroom – to the tiny pinwheel shapes of the delicate collared parachute.

No two woods are the same, so the fungi you discover may reflect subtle differences in soil type, drainage and prevailing weather.

What are mushrooms?

Mushrooms or toadstools – call them what you will – are the colourful manifestations of subterranean fungal webs or mycelia, which comprise the real engine room of our woods.

Some fungi are saprotrophic: they obtain their nutrients by breaking down organic remains. Others form mycorrhizal associations with trees or other plants, in which both partners share nutrients: the mycelia bond with the root cells and thus ferry nutrients to the hosts. Up to 90% of all plants are thought to have such fungal ‘helpers’.

One of the most unusual-looking groups of fungi is the earthstars, which have a spore sac, sometimes raised on a stalk, and surrounded by rays. There are more than 15 found in the UK, and our earthstar identification guide by naturalist Phil Gates describes seven to look out for.

Putting a name to the trees in a wood will tell you what fungi to expect. For example, the magpie fungus occurs mainly in beechwoods, for example, while the sickener prefers pines and the larch bolete is (you’ve guessed it) a denizen of larch plantations.

How to identify mushrooms

- Join a fungi foray – it’s the best way to pick up ID tips. Many local conservation organisations organise forays on their reserves.

- Take spore prints from your fungi. Place the cap on a piece of clean paper, cover it overnight and next morning you should have a perfect spore print. Fungi fun!

- Specialise in a few fungal types, such as colourful waxcaps, coral fungi or boletes. Report unusual finds to your local records group; find a list here.

Correctly identifying fungi to species level is extremely difficult and many species are poisonous, and even fatal, so if you wish to forage fungi, we would advise doing so with an expert.

All illustrations by Felicity Rose Cole, unless otherwise credited

How to identify woodland fungi

Chanterelle mushroom (Cantharellus cibarius)

Chanterelle mushrooms can be found in coniferous and deciduous woods. Brilliant yellow; gills run part of way down thick stem. Edible (delicious).

Chanterelles are common and widespread in the UK.

False chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aureantiaca)

Standing out like a beacon in dark conifer woods, the false chanterelle is a common, orange-yellow fungus that appears in small groups this month. It can also be found heaths. Its cap measures between 3-8cm across. Its fluted gills extend down the stem like those of the true chanterelle, but are closer packed, and the flesh is thinner than that of its edible namesake. Never eat a false chanterelle – its toxins cause hallucinations.

Horn of plenty mushroom (Craterellus cornucopioides)

The horn of plenty mushroom is a woodland mushroom that favours deciduous woods and is often found in groups. Blackish, funnel-shaped or tubular cap with frilly edges.

They're quite localised, but horn of plenty mushrooms are easy to see in some spots.

The sickener mushroom (Russela emetic)

Sickener mushrooms occur in pine woods. A ‘brittlegill’ with a scarlet cap and pure white gills and stem; gills break easily when touched. Poisonous.

Sickener mushrooms are common and widespread.

Charcoal burner mushroom (Russell cyanoxantha)

You can find charcoal burner mushrooms in deciduous woods. A ‘brittlegill’ with a lilac or red wine-coloured cap, often with olive tints.

Common and widespread in the UK, it shouldn't be hard to find a charcoal burner mushroom.

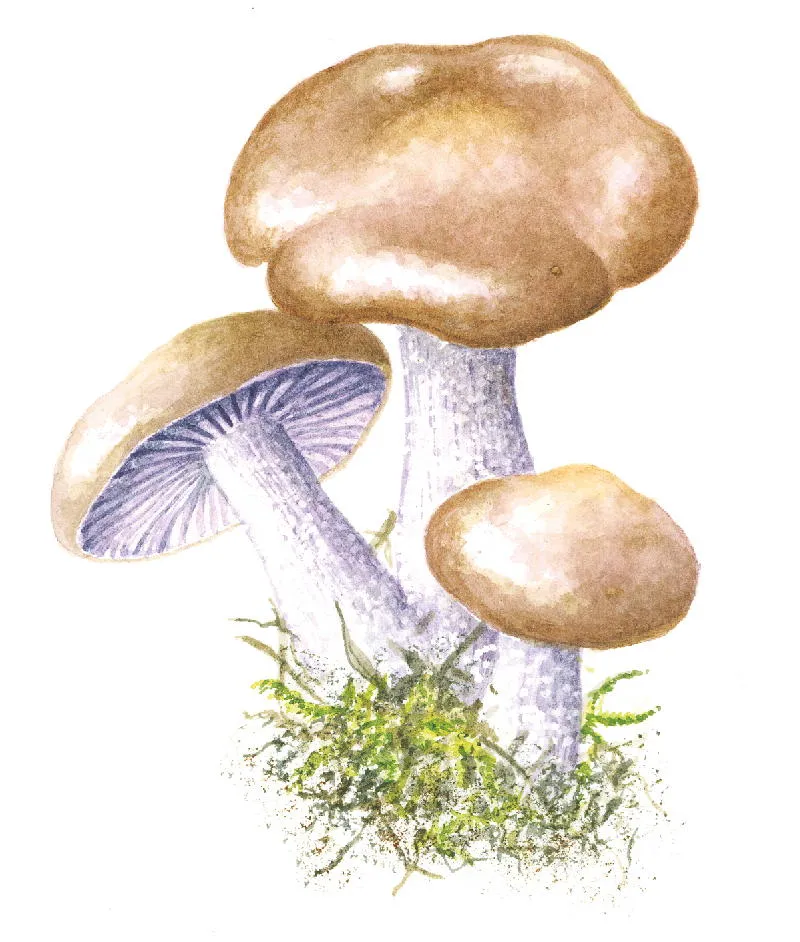

Wood blewit mushroom (Lepista nuda)

Cap: 6-14cm. Wood blewit mushrooms are found in deciduous woods and hedges. Rich tan cap; lilac stem and gills. Has a sweet, perfumed smell. With age, the bluish-hued cap turns ochre, with wavy edges.

Like many other mushrooms here, wood blewit mushrooms are common and widespread in Britain.

Larch bolete mushroom (Suillus grevillei)

As you might guess from then name, larch bolete mushrooms are found under larches. Cap sticky, orange when young, yellower as it matures. Has pores instead of gills.

Larch boletes are localised but easy to see in the right spots.

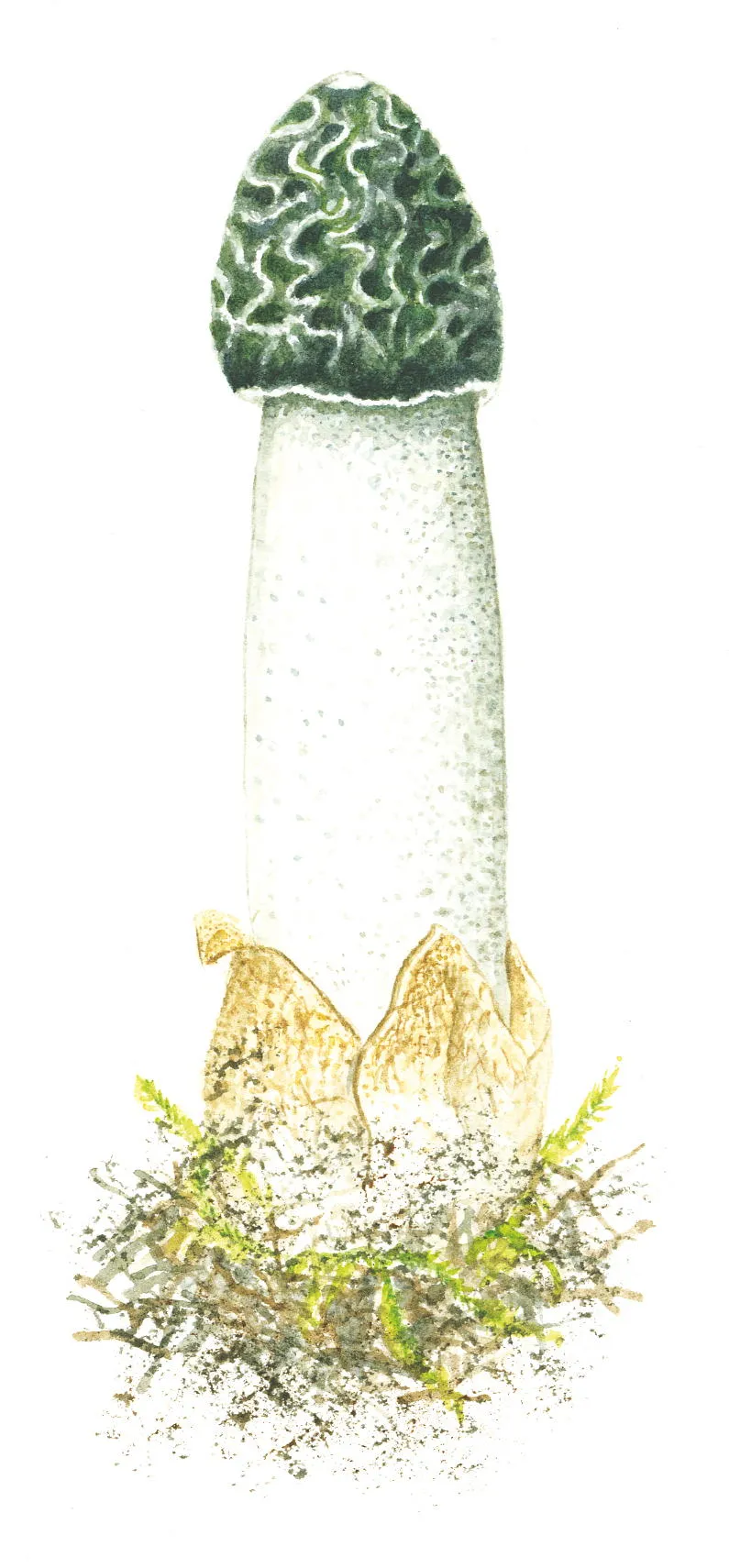

Common stinkhorn mushroom (Phallus impudicus )

Common stinkhorn mushrooms aren't particularly choosy and can be found in all kinds of woods. Cap covered in slime when fresh; releases foul smell to attract flies that spread its spores.

Given their non-choosy nature, it's not surprising that common stinkhorns are common and widespread.

Hedgehog mushroom (Hydnum repandum)

Hedgehog mushrooms can be found in most woodland types. Cap creamy on upperside; underside has soft, pale spines (hence the name).

Hedgehog mushrooms are common and widespread.

Violet webcap mushroom (Cortinarius violaceus)

You'll mainly find violet webcap mushrooms in birch woods. Big, beautiful mushroom with a rich violet cap; browns with age.

Violet webcap mushrooms are scarce and will generally require some thorough searching.

Verdigris roundhead mushroom (Stropharia aeruginosa)

Verdigris roundhead mushrooms occur in all types of woodland and also on heaths. Unique turquoise colour with white, fleecy patches when young. Poisonous.

Common and widespread, verdigris roundhead mushrooms shouldn't be too tricky to find but are well worth searching out for their unique colour.

Magpie fungus (Coprinus picaceus)

Height: up to 12cm. You'll find magpie fungus in deciduous woods, mainly beech or, occasionally, oak. Bell-shaped cap with irregular white patches, which blackens and liquefies to ‘ink’ as it ages.

Magpie fungus doesn't exist everywhere in the UK, but it's easy to see in some spots in its localised distribution.

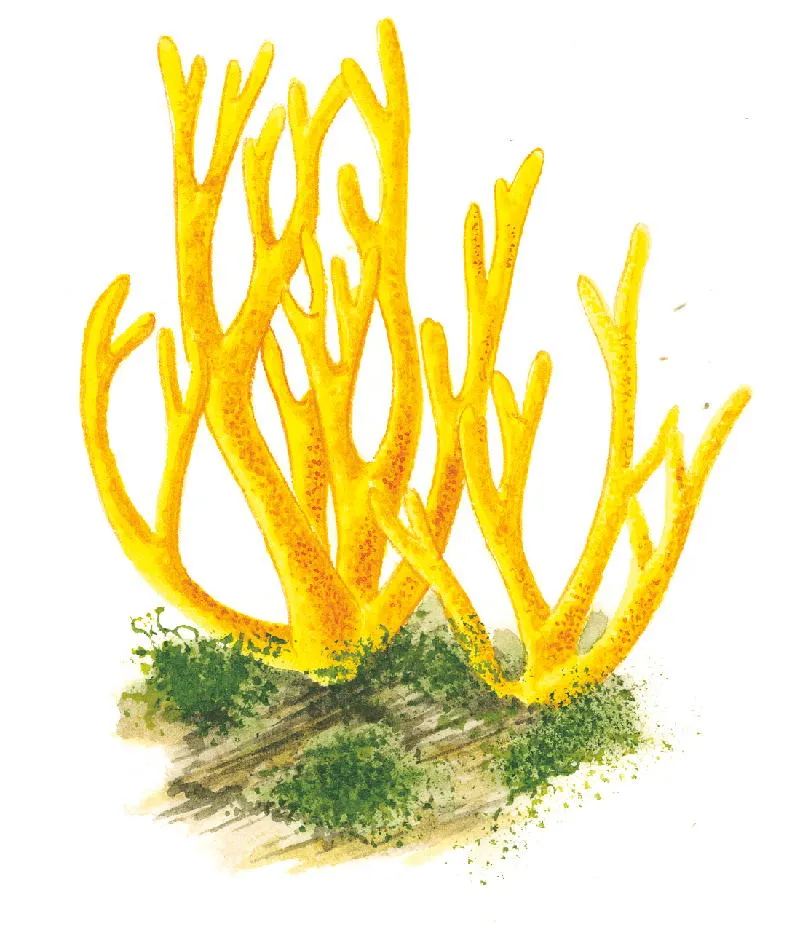

Yellow stagshorn fungus (Calocera viscosa)

Measuring between two to ten centimetres in height, yellow stagshorn fungus is a very striking in species with antler-like forking branches. It is found in coniferous woods, in small clumps on rotten logs and stumps. Although it is named as yellow stagshorn, it can often be orange in colour too. It can be quite slimy and sticky when wet.

It was first described by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon in 1794. Yellow stagshorn fungus is common and widespread throughout Britain and Ireland. It can be found throughout much of the year, but particularly in autumn.

Coral spot fungus (Nectria cinnabarina)

Found mainly on the smaller branches and twigs of beech trees, the pink-orange fruiting bodies of coral spot fungus can also be found on sycamore, horse chestnut and hornbeam.

The species is common and widespread throughout Britain and Ireland. It was first described in 1791 by the German mycologist and theologian Heinrich Julius Tode.

Many-zoned polypore (Trametes versicolor)

Banded brackets with pale edges; fresh brackets often purplish ‘bloom’. Common on rotting logs.

The goblet (Pseudoclitocybe cyathiformis)

Cap: 5–8cm. Deciduous woodland, among leaf litter or on well-rotted logs; often persists well into winter.

Plums and custard (Tricholomopsis rutilans)

Cap: 4–12cm. On conifer stumps, especially pine. In spite of its name, bitter-tasting and not edible.

Lilac bonnet (Mycena pura)

Also referred to as the lilac bellcap, this small fungi has a cap measuring between three to five centimetres across (when fully mature) and is not always purple in colour. It can also be yellow or white in colour. The species is often found under beeches, but also in mixed woodland and some grasslands. Although it smells strongly of radishes when crushed, it contains muscarine which is a deadly toxin and should be considered potentially poisonous.

It is found throughout Britain and Ireland, and is typically seen between June and October. The species was first described in 1794 by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.

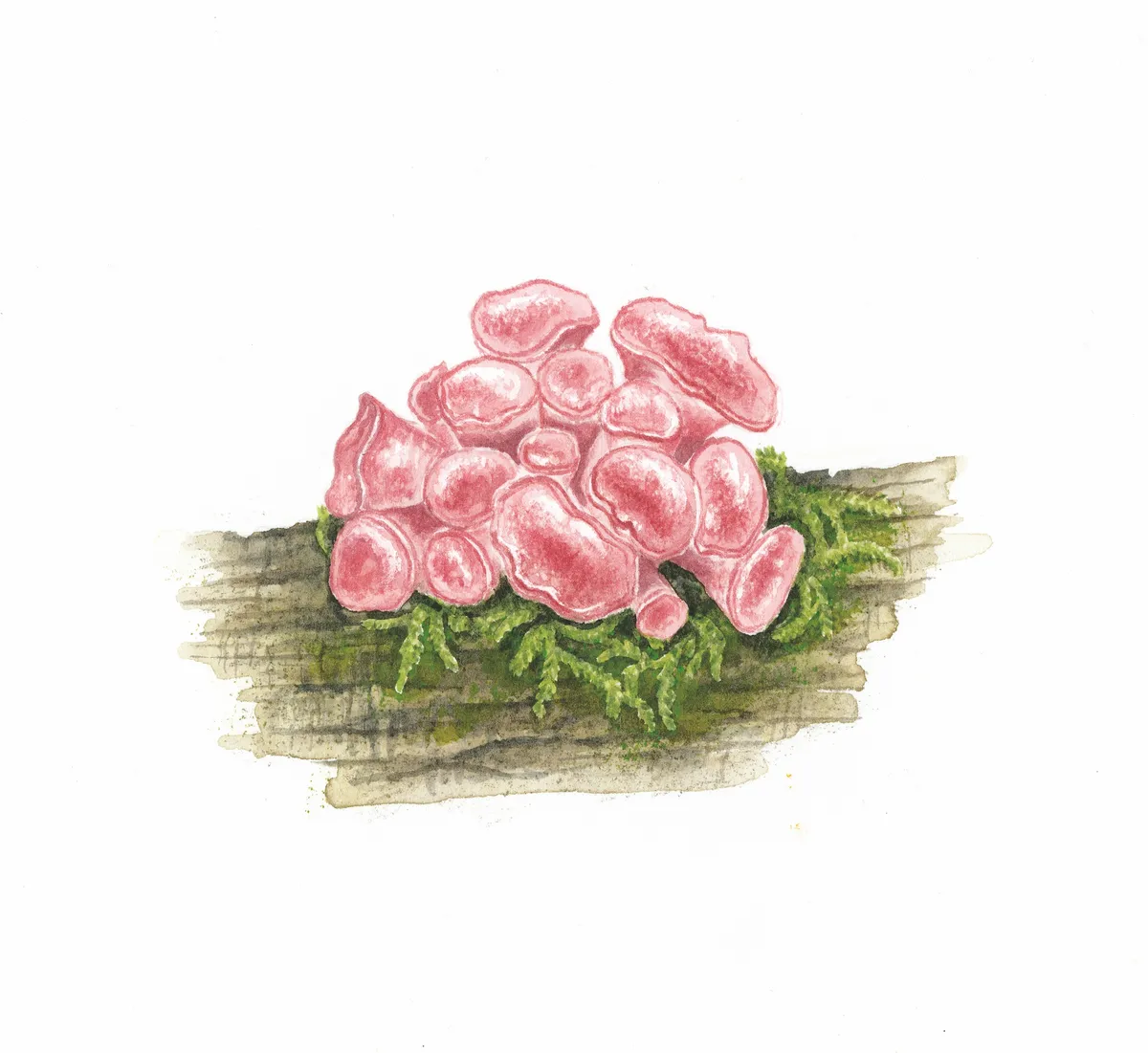

Purple jelly disc (Asocoryne sarcoides)

This weird-looking gelatinous mass consists of pink-purple coloured discs, and is mainly found on the trunks and branches of dead beech trees. It is common and widespread throughout Britain and Ireland. The brain-like clusters glisten when wet.

Each individual fruitbody measures between 0.5 to 1.5cm across, whilst clusters can measure between five and ten centimetres.

As it is very jelly-like, it sometimes gets mistaken for species from the genus Tremella, which are the true ‘jelly fungi’.

The Dutch naturalist Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin was the first to describe the species, in 1781.

Collared parachute (Marasmius rotula)

Cap: about 1cm. On dead roots, twigs and branches of deciduous trees. Gills resemble wheel spokes.

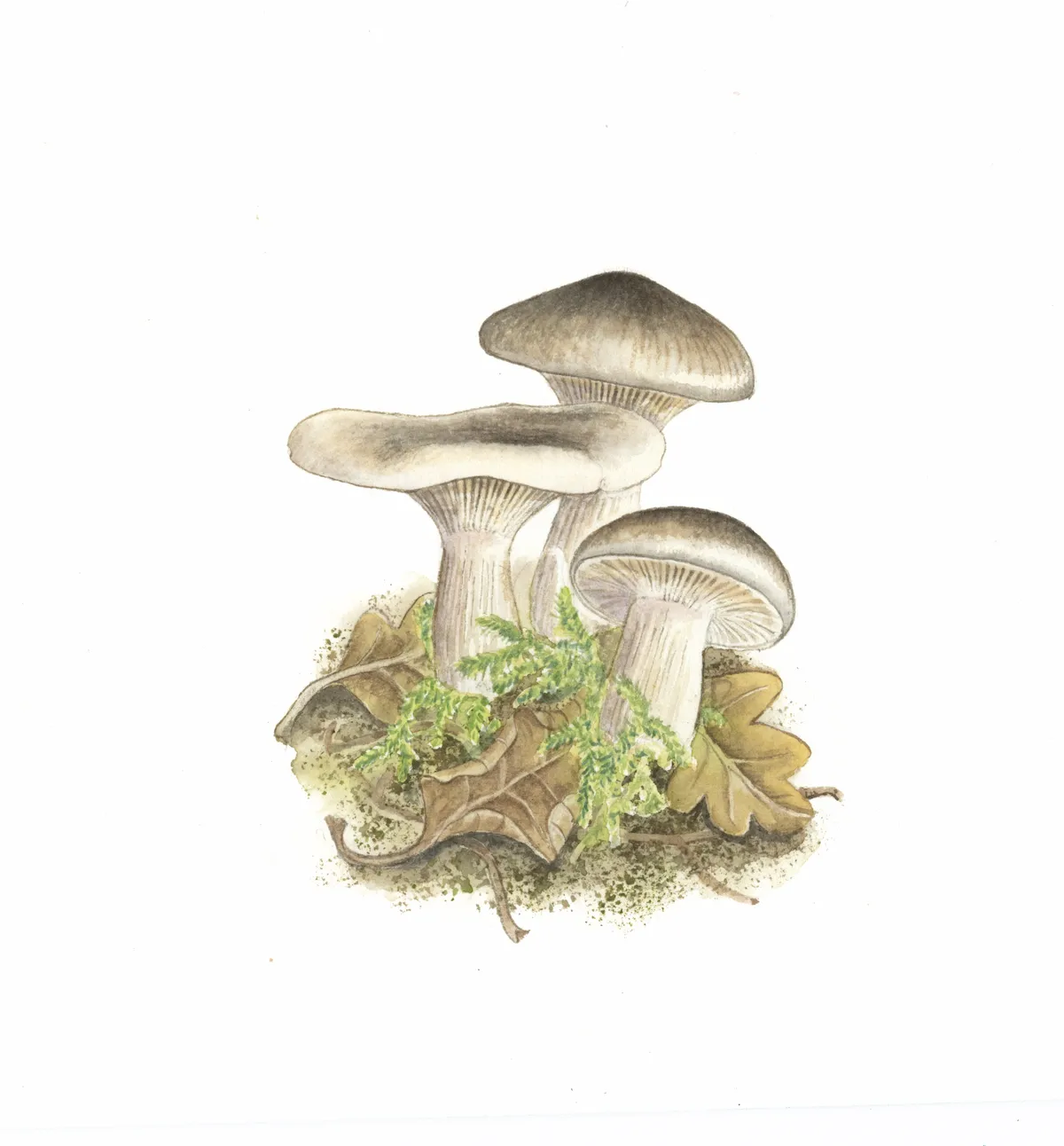

Clouded funnel (Citocybe nebularis)

Cap: up to 20cm. In deciduous and coniferous woods, forming large fairy rings. Smells fruit-like, but poisonous.

Sulphur tuft (Hypholoma fasciculare)

Cap: 4–8cm. Abundant in all types of woodland, on decaying stumps in big golden groups. Blackens with age.

The prince (Agaricus agustus)

Cap: up to 20cm. In open woodland, under conifers or deciduous trees. Delicious – highly prized. Scare: searching needed

King Alfred’s cakes (Daldinia concentrica)

The round and hard blackish fruiting bodies measure between two to ten centimetres across and look a bit like coal (leading to one of their alternative names of coal fungus), becoming darker as they age. They actually start off pinkish-brown in colour until they become mature.

Slicing them open reveals concentric rings inside. They can be found on the trunks of dead and decaying trees in deciduous woodland, especially fallen ash and beech branches.

King Alfred’s cakes are common and widespread throughout Britain and Ireland, and was first described by British mycologist James Bolton in 1791.

The common name of ‘King Alfred’s cakes’ comes from the legend of King Alfred from the 9th century. He took refuge with a peasant women when fleeing from Vikings, and she asked him to keep a watch on her baking cakes. He let them burn, and was scolded by her.

They are also known as ‘cramp balls’ as it was believed that if you carried them with you, you’d be protected from cramps.

Old King Alfred’s cakes are popular with bushcrafters as they can be used as tinder to light a fire, burning slowly.

Sessile earthstar (Geastrum fimbriatum)

The sessile earthstar has a dimeter of only two centimetres, and becomes grey with age. It has between five and nine rays, which are cream in colour. It occurs across the UK, but is more common in England than the other countries.

It can be found on undisturbed woodland floor, often near hazel. The fruiting body comprises an acorn-like spore sac and curling rays. Usually seen between August and November.

Learn more about earthstar identification in our guide by naturalist Phil Gates.

Main image: Magpie fungus on woodland floor in St Victor de Reno, Normandy, France. © David Courtenay/Getty