Rodney Stotts has always loved and been fascinated by animals, but particularly raptors. “Ever since I was a kid, birds of prey amazed me,” he says. He would bunk off school in order to visit the zoo. “Raptors, vultures, eagles – they were so fierce with their sharp killer talons. The birds of prey were also feared and misunderstood, just like I was.”

The book opens with Rodney getting distracted during a drug deal by a red-tailed hawk landing near the window with its rodent prey. While Rodney’s supplier weighs out the coke, Rodney is mesmerised by the bird instead.

Strangely, it’s the drug dealing that prompts a career in nature. In order to own an apartment, and be able to store more guns away from his mother, Rodney needs a job. And he lands one with the Earth Conservation Corps, clearing rubbish from the Anacostia River. While he continues to deal drugs and has a stint in jail, this marks the start of what will eventually transform his life and set him on the road to becoming a master falconer.

Alongside Rodney’s personal journey, the book also provides insights into what falconry involves, and what’s required of falconers, such as the strict rules in place regarding catching, housing and looking after birds. With the exception of a couple of individuals, Rodney’s birds are wild ones: caught as juveniles, flown and hunted for a couple of years, and then released back into the wild as adults.

It’s an emotional and moving read, with losses and difficulties throughout, but also full of hope and the importance of connections with nature.

- Pre-order now (or buy on Kindle) from Amazon, Bookshop, Hive, Waterstones

Read our interview with Rodney Stotts:

Why do birds of prey fascinate you?

Ever since I was a kid, birds of prey amazed me. Once I was old enough, I used to hook school and take the subway and bus to the zoo to see the raptors. Raptors, vultures, eagles — they were so fierce with their sharp killer talons. The birds of prey were also feared and misunderstood, just like I was. Actually I like all animals and birds, but I’m drawn to raptors because I like to hunt them. I guess you could say I’m an animal junkie. With birds of prey, you really have to earn their trust and respect them. Once they accept you, it’s easier to work with them and eventually hunt them.

What prompted the shift from drug dealing to working with nature?

It didn’t happen overnight. It was mostly just a shift into trying to do something better, something that made a difference – a positive difference. At first, working to clean up the Anacostia River was just a job for me. Working with nature gave me time to think, and the more I thought, the more I wanted to start turning my life around. Sometimes we can be our own worst enemy. As I tell the young people I work with: sometimes you have to get out of your own damn way.

What was it like working on clearing the trash from the Anacostia River?

At first, working to clean up the Anacostia River was just a job for me. I needed money and this particular job was outside so I figured it would work for me. In those days, the Anacostia was like this mysterious, moving creature. It was a dumping ground for all sorts of trash and even the occasional murder victim. The other young workers and I started pulling tires, bikes, plastic bottles, mattresses, and other debris out of the Lower Beaverdam Creek—a tributary of the Anacostia River.

In the first three months, we hauled more than 5,000 car tires out of the river and ended up filling close to twenty huge dumpsters with trash. Except for a few little minnows and crawfish, no life was visible. We didn’t even see any small birds, like robins or sparrows.

One day, several weeks in, we were still pulling stuff out of the river when a great blue heron landed nearby. We couldn’t believe it. The heron had found a space with no trash and liked it. After just a few months, we could see the bottom of the tributary and the water starting to flow. Seeing wildlife return to a place that had once belonged to them started to change me, and it inspired me to want to do more.

How did you transition from clearing rubbish on the Anacostia River to becoming a falconer?

After working on the Anacostia, the group I was working with – Earth Conservation Corps – started sheltering injured raptors, such as hawks and owls. The birds we took in were too injured to be returned to nature so we used them to teach kids about birds of prey and conservation.

After a few years of that work though, I wanted to do more, and I wondered what the next step would be. What if we could get birds of prey before they got injured, help them through their first year of life (when they are most at risk of getting hit by trucks or cars or snared in electrical wires) and then release them? That’s what falconry is about. And to me that was similar to working with young people at risk: if you can help through the early danger zones, they have a better chance of living full lives.

How did you feel when your son said he wanted to become a falconer too?

I remember the day Mike called me and said he wanted to be a falconer. I was so proud because he told me he wanted to follow my example. Yeah, that made me proud. I always knew that someday Mike would follow in my falconer footsteps — I just didn’t know when. Even when he was little, I would see him watching birds with the same intent curiosity that I had.

I know Mike is proud of me, of the man I have become. I can hear it in his voice. But everything was different 15 years ago. Mike was only eight when I got locked up on drug possession charges. He told me later how he cried when one day I was just suddenly gone. He had seen other men in the neighbourhood and his friends’ fathers get locked up and never return. Those memories are painful for me, but they are in the past, and I’m all about moving forward.

How does it feel when you release your birds back into the wild?

It feels great when I’ve trapped a raptor, cared for it, and then set it free. By law, if you accidentally trap an adult bird of prey, you need to release it immediately. Falconers can only trap juvenile birds. And you cannot release a raptor that is injured or is not native to your area.

Sometimes, before I release a raptor, I ask people to send me intentions, and then I’ll have a small ceremony where I read everyone’s intentions and then release the bird, sending it and the intentions or prayers up into the sky.

Why did you set up Rodney’s Raptors?

I created Rodney’s Raptors because I want to give people — especially young people — the experience I have almost every day: being up close and personal with nature, animals and birds of prey. Immersing myself in the natural world made me want to change who I was as a man, and what makes me happy is when I see the same thing happen to others.

What is Dippy’s Dream and your plans for it?

Dippy’s Dream is named after my mom — Dippy was her nickname — who died in 2015. It’s still a work in progress, but it is a human sanctuary, and by that I mean that is a place where people will come to breathe fresh air, relax, and heal from the emotional bruises life can leave. It’s located on seven acres of property in Virginia, and I’m pretty much building it single-handedly.

People can camp, interact with animals like my horses and raptors, learn how to grow their own food, and just feel free, at least for a little while. Dippy’s Dream is donation-based. You pay what you can afford, and if you can’t afford anything, that’s ok. I’ve long believed that just because someone is poor, doesn’t mean they should be locked out of certain experiences. How does that change anything? I welcome any and all donations, and you can go to my website to learn more.

How has the pandemic affected your plans?

I regularly give presentations at nature centres, book stores, schools, and other places. Those are a source of income for me — and for Dippy’s Dream — and it all just shut down. It was rough for a while. On the other hand, the pandemic helped me in a way because I had so much time, I was able to make a lot of progress on Dippy’s Dream like building structures for my animals and clearing land.

What prompted you to write this book?

To tell you the truth, I had never thought about writing a book. I just like doing my thing, teaching people about nature and conservation, and now building Dippy’s Dream. One day I was approached by a writer who had been to one of my presentations and thought I should write a book. At first I wasn’t really interested but then I talked to Mike and a few other people. I started thinking that maybe a book could inspire some people to get more involved in nature and perhaps visit the sanctuary I’m building. Selfishly speaking, it’s also my hope that the book inspires people to donate to Dippy’s Dream.

What do you want readers to take away from your book?

It’s so easy for humans to go through their day and not think about or even notice nature. That’s a shame because nature is where all sorts of magic happens. Sometimes people think they’re too busy. I would challenge them to at least once a day, look up. There’s a whole world up there: birds, clouds, insects, trees, leaves, branches, stars. And it is there for the taking with a simple tilt of the head.

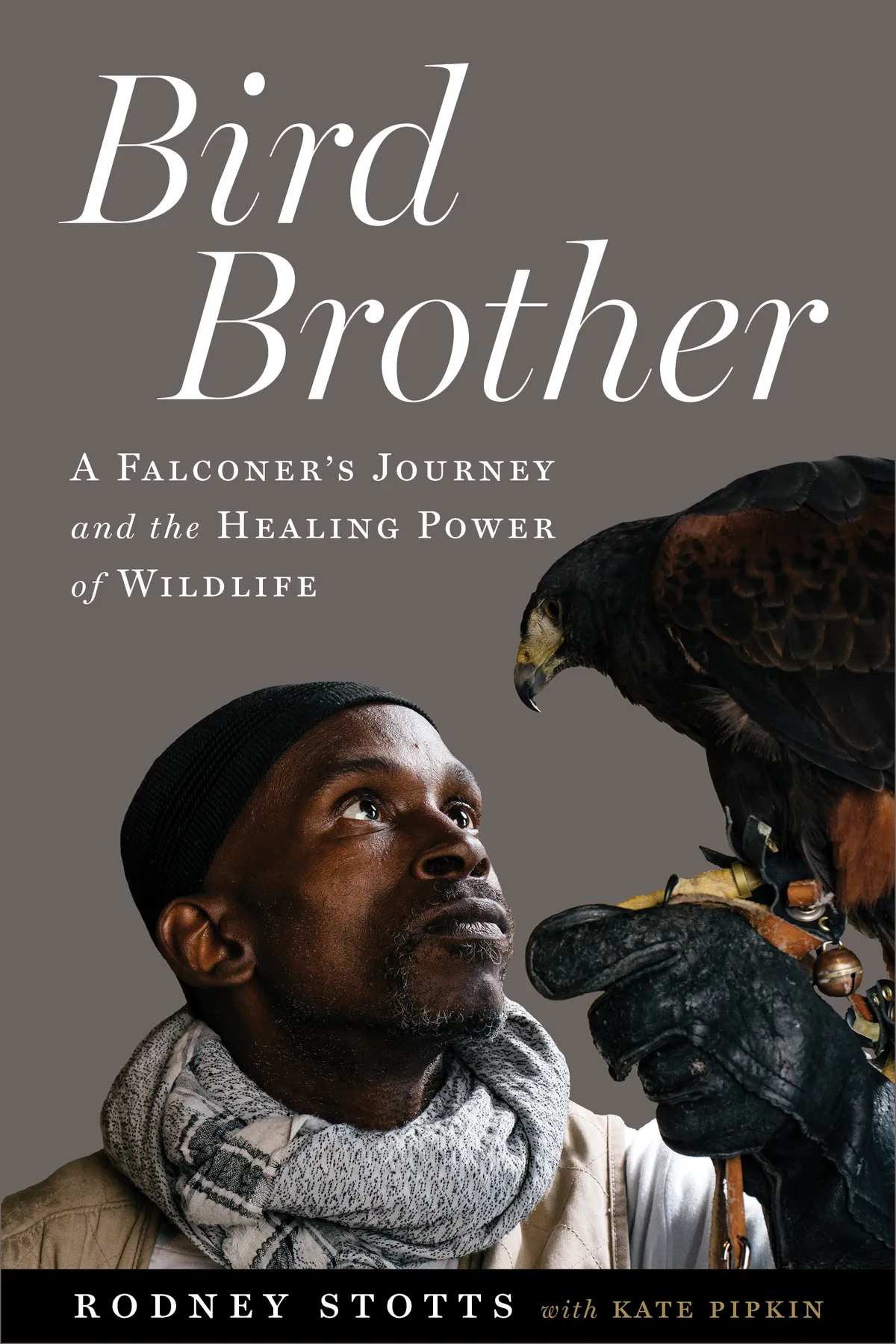

Main image: Rodney Stotts sits with his harris hawk, Agnes, at the Wings Over America raptor sanctuary in Maryland in 2016. © Greg Kahn