During the mid-1990s, Becky Ingham was selling newspaper advertising space in London while wondering how to get back into marine biology.

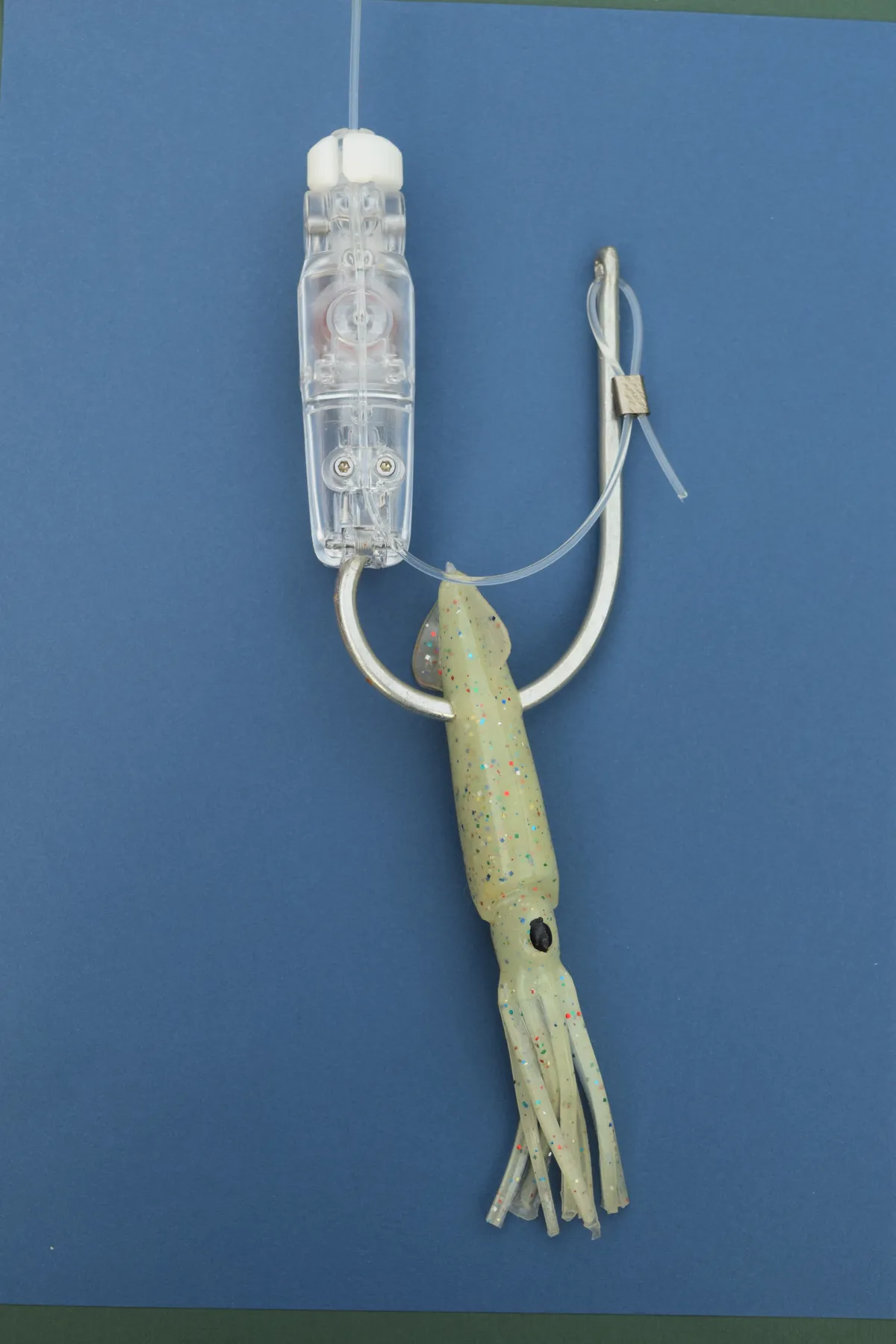

Meanwhile, in Devon, two inventors had an idea for a way to protect albatrosses and other seabirds from a grisly death on longline fishing hooks. Happily for all concerned, their paths would cross, and the result is Hookpod (below), a device that could reduce seabird by-catch drastically.

Ingham’s first step was to undertake a master’s degree in fisheries. “At the end of that, I had four months to come up with a way to pay for it.”

Which she did by taking work as a fisheries observer in the Falklands. “That was where by-catch, the sheer scale of it, hit me. I decided I wanted to help solve it in some way.”

The sheer scale of by-catch hit me. I decided I wanted to help solve it.

That was also where Ingham met Ben Sullivan, a biologist with BirdLife, who had been approached by inventors Pete and Ben Kibel with their idea.

“When I returned to the UK to have my second child, Ben asked if I’d be interested in joining the team,” says Ingham.

At the time, longline fishing fleets were required to deploy a combination of measures to protect seabirds – weights that sink the hooks quickly, bird-scaring streamers (or tori lines) and setting fishing lines only at night.

These measures are effective, but only when used properly. Tori lines often get tangled, while as few as 2 per cent of vessels adhere to the night-setting rule.

Hookpod had the potential to simplify things. It consists of a pressure-sensitive plastic housing that only releases the hook when it reaches a depth of 20m, beyond the range of diving birds.

Trials in New Zealand, Brazil and Japan suggest it reduces by-catch by 95 per cent. “The more research we do, the more data we collect, the more feedback from fishermen we get, the more confidence people have in it,” explains Ingham.

But there was a problem: fishermen required to use tori lines and the like, have little incentive to invest in Hookpods. Regulatory changes were needed.

In January this year, the Western Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) became the first of the four international fisheries bodies to approve Hookpod as a stand-alone by-catch mitigation measure, making it attractive to fishermen.

Ingham is hopeful the other commissions will follow WCPFC’s lead. Even that would only cover the high seas; inshore waters are regulated by individual nations. There’s also the small matter of marketing it to fishermen.

As Hookpod’s only full-time employee, Ingham has her work cut out. “We’re very lucky that our directors and shareholders are real enthusiasts. They give up a lot of their time to help.”

Public support has also been crucial. “It’s been a long road,” says Ingham. “And yet, in a way, this is only the start.”