What are muntjac deer?

Muntjacs are a small stocky type of deer, widespread in British woodlands.

How big are muntjac deer?

They are often overlooked because, being just 50cm high and no bigger than a medium-sized dog, they are hidden by tall vegetation for much of the summer.

Adult male weigh between 10 to 18kg , while adult females weigh between 9 -16kg.

When is the best time to spot them?

Therefore winter is the ideal time to look for them. They breed throughout the year, so there are few seasonal differences in behaviour.

What do muntjack deer eat?

Muntjac deer are herbivores, and enjoy trees and shrubs, shoots, herbs, berries, nuts and fungi.

Muntjac deer scent glands

Muntjac are largely solitary and territorial, and they use scent to communicate more often than deer that live in larger groups.

Look out for individuals rubbing the long v-shaped slits on their foreheads (their frontal glands) onto twigs or the ground.

They also have two large glands located just in front of the eyes, called the pre-orbital glands.

Muntjac frequently lick these with their long tongues, presumably in order to help them recognise their own scent.

During periods of excitement, such as courtship or when defecating and urinating, these glands may be opened and wiped against twigs. Males scent-mark more than females, and dominant males more than subordinates.

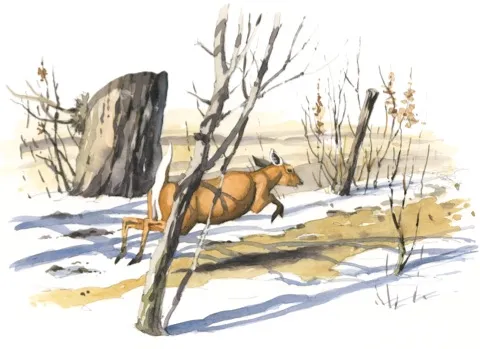

A disturbed muntjac usually gives a few barks, then flees with its tail held aloft. © Federico Gemma

Do muntjac deer bark?

Muntjac are extremely vocal, hence their other name ‘barking deer’. Though it is called a ‘bark’, the sound is more like a scream and can be mistaken for a fox.

A muntjac will invariably give a few barks when disturbed – this is usually the first sign that you have been spotted. Then all you are likely to see is the animal bouncing off with its tail held up, displaying the white underside as a warning to other deer.

Does often call just after giving birth. They may bark more than 100 times in succession to attract bucks. They mate within hours of giving birth, so females spend virtually all of their adult lives pregnant.

How big are a muntjac's fangs and what do they use them for?

Odd though these adaptations are, it is the ‘fangs’ that really seem out of place. Most prominent in the adult male, the elongated upper canines are up to 6cm long. Whereas most male deer use antlers to fight and display their fitness, the male muntjac has only an elementary set. Once again, the tangle of shrubby habitats preferred by this species explains why. Big antlers would simply be impractical; the fangs are for close-up combat.

There are many older bucks that wear the resulting scars on their faces and flanks, and have ragged ears. But there’s one more surprise. These extended canines are hinged, and can be folded back when not needed, so as to not get in the way of feeding. They’re more flick knives than daggers.

Nick Baker

Are muntjac deer native to the UK?

Muntjacs are not native to the UK, but since being introduced at Woburn by the 11th Duke of Bedford around the turn of the 20th century, the species has done well here.

Why are muntjac deer considered a pest?

For both gardeners and many conservationists, muntjac deer is public enemy number one.

It has high reproductive potential, and one particular problem is its penchant for browsing out low growth, including much-loved woodland wildflowers such as bluebells and primroses. There is also a suggestion it might be implicated in the degradation of nightingale habitat. The species appears to be spreading from its original range in south-east England at an alarming rate, causing ecological upset in its wake.

Nick Baker

Find out more about the work of illustrator Federico Gemma.

Click here to read other understand mammal behaviour articles.