With iridescent purple wings on the males, and as one of the UK's largest butterfly species, the purple emperor is a much sought-after species by nature lovers. However, it's surprisingly elusive and has some unusual tastes. Discover more in our expert guide by naturalist and author Matthew Oates.

Where are purple emperor butterflies found?

The purple emperor is found in and around woodland in much of central southern, south east and eastern England, and can be anticipated in parts of the West Country, the western Midlands and eastern Wales.

Abroad, it is a species of the middle band of Europe, avoiding the hottest and coolest regions.

Two other species of emperor butterfly occur in Europe, the lesser purple emperor and Fryer’s purple emperor. In both, the males possess a golden sheen over the purple iridescence. Further east, other Emperor species occur, some without any purple.

What is the scientific name of the purple emperor butterfly?

This butterfly trades under the scientific name of Apatura iris. It is the only species in the Apatura genus in the UK.

‘Apatura’ (Greek) has something to do with deception, referring to the male’s deceptive purple iridescence, seen only from certain angles. Iris was the winged messenger of the Roman gods, who appeared in the guise of a rainbow and was a demi-god in her own right.

How to identify a purple emperor butterflies

In the UK, the purple emperor is quite distinctive. It is the size of a small bird or bat, is a powerful flyer, and tends to glide and soar high up around medium-sized trees. Seen from below, it appears as a black butterfly with distinctive white bands and spots.

The purple emperor has black wings, but when caught at the right angle, the males' upper wings have a rich and iridescent blue-purple colouration. Females can look similar to white admiral butterflies, but have an orange-ringed eyespot.

The white admiral is similar, but is much smaller, flits rather than soars, and tends to fly much lower. The upper wings are brown-black in colouration, with a white band colour and no purple. If in any doubt, it’s not an emperor: the purple emperor leaves you in no doubt.

How to identify purple emperor caterpillars and pupae

Purple emperor caterpillars go through five instars before pupating, developing two horns on their head in the second instar. They hibernate over winter in their third instar form, and recommence feeding on sallow in spring.

When fully grown, the caterpillars will leave their feeding site and travel, sometimes to the top of the sallow tree, to pupate.

The pupa is between 3o t0 35mm in length, and matches the green of the sallow leaves, darkening slightly before the butterfly emerges in summer.

When is the flight season of purple emperor butterflies?

The flight season lasts about six weeks, though numbers are low for the last three. Traditionally, the purple emperor season started in early July, peaked mid-month and petered out in early August, though there were always early years, like 1976, when it started in late June.

Now, with climate change, the season starts in mid-June, peaks in late June or early July, and is finished by August. We may even get a partial second brood in the autumn.

How numerous are purple emperor butterflies?

For the last hundred years, populations have been so low that we decided that this is by nature a scarce insect which only occurs at low population level. That’s nonsense, it can occur in fair numbers, though not (yet) in the abundance of some of our blue and brown butterflies.

At Knepp Wildland in West Sussex, it is relatively numerous, such that well over a hundred individuals can be seen in a day, by those who know how to look.

Crucially, the techniques for spotting purple emperors are unique: you look up, around the trees, and never look for them around flowers, which they seldom if ever visit. Birders are particularly good at spotting emperors.

What do purple emperor butterflies eat?

Female purple emperor butterflies lay their eggs on the upper sides of sallow and willow leaves, usually in fairly shady situations. These hatch after two to three weeks.

The insect then spends ten months in the larval state, five of them in hibernation on twigs, usually in forks or by buds. Larvae feed very slowly before hibernation, but rapidly during May. They usually wander far before pupating, spending some three weeks as pupae.

The adults rarely visit flowers. Instead, like many tropical butterflies, they imbibe minerals from the woodland floor, from sap runs on oak trees, and sometimes from honeydew (the sticky secretion of aphids on leaves).

Victorian butterfly collectors used to bait them down, with dead rabbits or worse, but today they descend to feed on indelicacies such as fox poo and worse, dog muck.

What eats purple emperor butterflies?

We don’t rightly know. The hibernating caterpillars are mercilessly predated, probably by tits. Pupating larvae and pupae also suffer high levels of predation, but we don’t know the details.

The adults are fairly predator-proof, and will readily attack birds (small, medium and large – as big as red kite and grey heron). Unfortunately, the males are so inquisitive and fearless that they get squashed on roads or mashed up in cement mixers!

Are purple emperor butterflies endangered?

The purple emperor butterfly went through a period of decline during the 20th century, due primarily to foresters regarding sallow bushes as obnoxious weeds, and cutting them down.

That prejudice is still a problem locally, but sallows are now generally regarded as great for biodiversity, and are allowed to grow in quiet corners.

Climate change may pose a new, greater set of problems, particularly in the form of mild winters which make proper hibernation (or diapause) difficult.

Atmospheric nitrogen deposition may present further problems, rendering sallow foliage unsuitable.

What work is being done to help purple emperor butterflies?

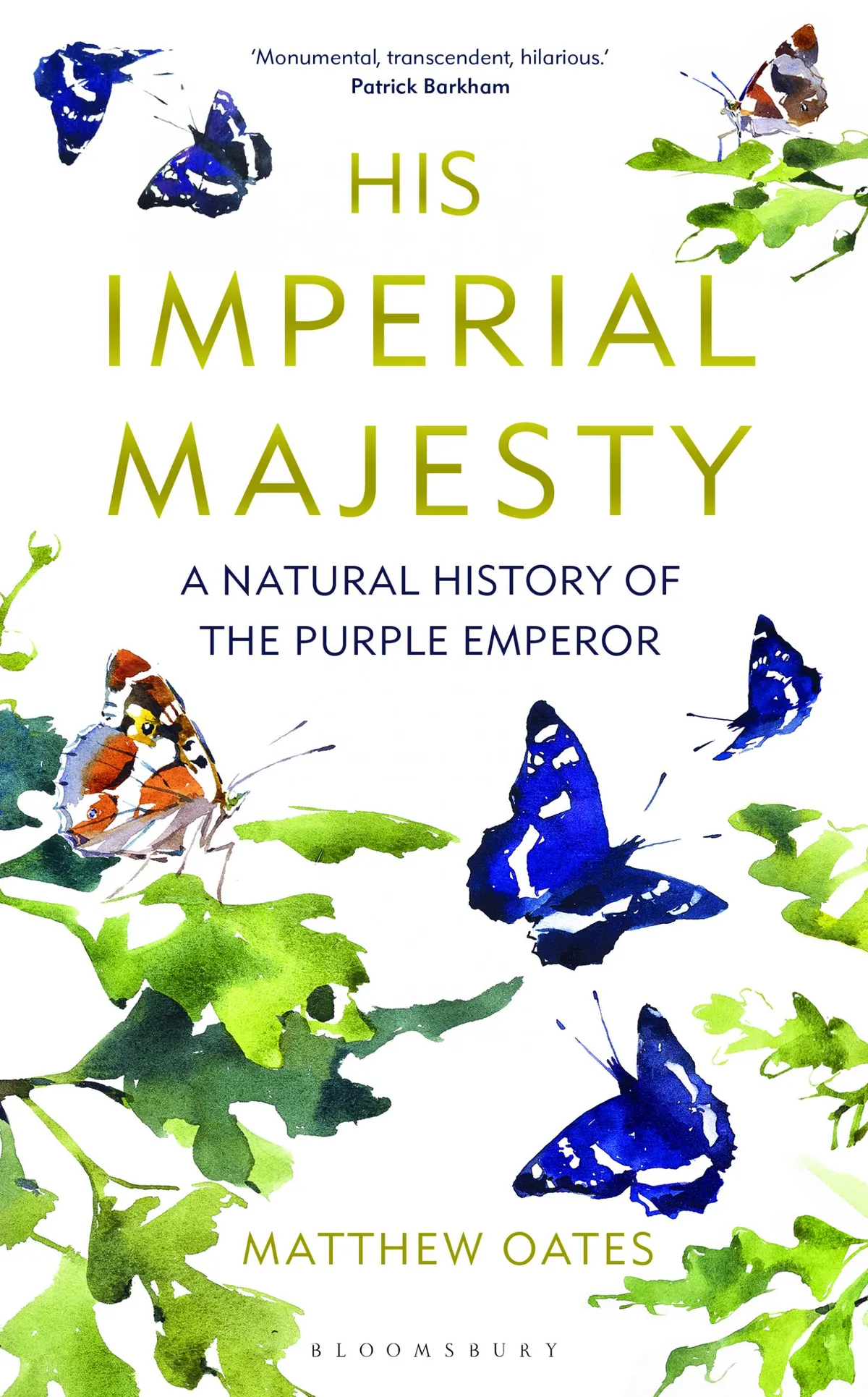

Above all, this butterfly needs understanding, and appreciating. Hopefully, my book, His Imperial Majesty: A Natural History of the Purple Emperor, will help give it the glorious future it deserves.

On the most basic level, it simply needs sallow trees – the more, the better. Its needs can be variously met, and it doesn’t have challenging conservation requirements. This is one butterfly we can quite easily ‘save’.

Where are the best places to see purple emperors in the UK?

At the moment, there are strong populations in Fermyn Woods (Forestry England), west of Brigstock in East Northants, Bently Wood on the Wiltshire and Hampshire border, and on the Knepp Castle Estate (private, with limited access) in West Sussex.

Other sizeable populations are developing, notably in the new Heart of England Forest in Warwickshire. These are Super League populations.

Mostly, the butterfly occurs in modest numbers in most of the larger woodland systems in southern counties. It is also being discovered in suburbia, with colonies on Hampstead Heath and in Richmond Park. It’s on the march - a good news story!

His Imperial Majesty: A Natural History of the Purple Emperor by Matthew Oates is published in hardback by Bloomsbury Wildlife.

Main image: Pristine male purple emperor displaying all four wings, at Fermyn Woods. © Matthew Oates/Neil Hulme