As a boy I collected pond life and proudly exhibited my micro-aquaria in my parents’ shed. I kept my charges in a carefully curated assortment of jam jars, tubs, tubes and tanks. One quiet evening I heard a determined buzzing. After a bit of triangulation, I discovered the rasping was emanating from a ‘jamming’ jam jar. Inside were water boatmen.

What are water boatmen?

Water boatmen are a family of aquatic insects.

What sound do water boatmen make?

I had just become aware of a secret world of insect acoustic ecology. My lively pond bugs were singing like crickets. I’ve since heard water boatmen called ‘water crickets’ in North America, and while they use different parts of their bodies to produce their scratchy tunes, the method is similar. Rubbing bits of the body together to create sound is known as stridulation.

How do water boatmen sing?

Most of my captives were lesser water boatmen, which are abundant and widespread. Close scrutiny of them singing revealed they did it by moving their front legs, which bear rows of tiny stiff pegs, against a ridge on their head. It was a slow stroking at first, warming up to a rapid vibration when in full flow. The sound was impressive given the insects were just 1cm long.

If only I had known then what I know now: several of the smaller specimens in my aquatic zoo were also singing, albeit in a very different way. Any pond dip can turn up many different but related species of water boatmen. However one family, the Micronecta, stridulate not with their legs but with their penis!

One common species, the 2mm-long Micronecta scholtzi, has been studied in great detail. The male rubs a ridge on its penis against ridges on its abdomen, thereby setting the pond – and any female in it – abuzz.

M. scholtzi has been recorded generating 99.2 decibels (although it usually sings around 78.9 dB), and this acoustic accomplishment is all the more incredible given the stridulating organ is fewer than 50 micrometers across – about the width of a human hair. The reason we’re not all stumbling around clutching our bleeding ears is that the water itself absorbs nearly all of the energy. And yet, if you’re tuned into the sound, it’s possible to sit by a pond when it’s quiet and actually hear the chorus. Or visit BBC iPlayer Radio, where you can hear a recording made for an episode of Radio Four’s Nature series (go to www.bbc.co.uk).

How loud are water boatmen when they 'sing'?

Normally, loud noises go with big animals, and blue whales and African elephants are indeed louder, at 188 dB and 117 dB respectively. But if you scale up the efforts of M. scholtzi, it is the loudest animal in the world for its size. What nobody understands is how it can be so loud, or why it needs to be.

It is thought that these bugs might use the bubble of air that they clutch to their bodies everytime they visit the surface as a kind of resonator, but the exact mechanism has acoustics engineers baffled. If we ever uncover the secret it may have useful applications in ultrasonic systems. As to why these insects need to be so loud, some biologists think it is down to a sexual selection process that has run away with itself.

With the males competing for females by engaging in sub-aqua sing-offs, the loudest are most often selected. In the sub-surface world of the pond, there are apparently no predators that hunt by sound. And with no ecological compromise, there is no disadvantage to being so loud and singing your socks off.

Nick Baker

How big are water boatmen?

Water boatmen are usually between 2.5mm and 13 mm (0.5 inch) long.

What do water boatmen eat?

Water boatmen eat plant debris and algae

Why do water boatmen swim upside down?

Water beetles and boatmen are aquatic insects, yet still obtain oxygen by breathing air via holes (tracheae) along the sides of their bodies, rather than directly from the water using gills.

They maintain a slim bubble of air against their bodies, trapped by water-repelling hairs that prevent saturation. This bubble, called the plastron, is replenished each time the insects come up for air.

Oddly, while beetles and lesser water boatmen generally break the surface back-first, true water boatmen (Notonecta), also called back-swimmers, swim upside-down and break the surface belly-up. The evolutionary origin of this difference is lost, but in Notonecta this unusual orientation is controlled by the antennae.

A bubble of air trapped around these appendages bends them up and away from the head.

If the insect becomes inverted the bubble pulls the antennae towards the head, which the insect detects and ‘rights’ itself. If the bubble is moved experimentally, with a fine needle, the back-swimmer can be tricked into front-swimming.

Richard Jones

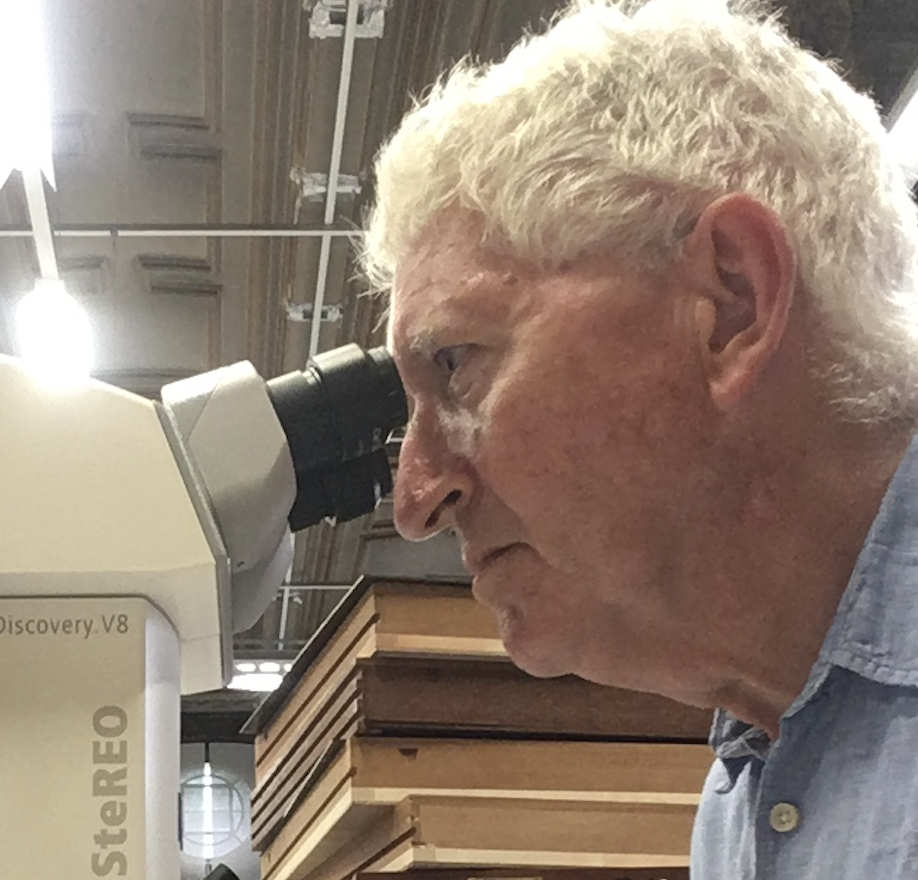

Main image: Water boatman (Notonecta) © Clouds Hill Imaging Ltd/Getty Images