Find out why Eurasian beavers are described as ecosystem engineers and keystone species, and what work is being done to reintroduce them in the UK in our expert guide by the Beaver Trust.

Where are Eurasian beavers found?

Eurasian beavers once lived all over Europe and Asia. Now they only live in small numbers in southern Scandinavia, Germany, France, Poland and central Russia.

Beavers became extinct in Britain in the 16th Century, hunted nearly to extinction for both its supersoft fur, meat and castoreum secretions. But, following reintroductions (both legal and illegal), the Eurasian beaver can now be found in many parts of Britain, including Devon, Cornwall and areas in Scotland.

Learn more about mammals in the UK:

Mammal quizzes:

What are Eurasian beavers related to?

Eurasian beavers are related to North American beavers, which are found throughout America and Canada and were introduced to Patagonia, South America.

Eurasian beavers and North American beavers are often mistaken as the same animal. Both species are rodents, yet several key physiological differences make them genetically separate.

Eurasian beavers are similar in appearance to the capybara, a huge rodent native to South America. They are both rodents with waterproof fur, however with their bigged webbed feet and claws, beavers are much better adapted to spending extended periods of time swimming and feeding in water. Eurasian beavers can remain underwater for up to 15 minutes at a time!

What is the scientific name of the Eurasian beaver?

The scientific name of the Eurasian beaver is Castor fiber.

The North American beaver's scientific name is Castor canadensis.

These two species are the only extant (living) species in both the Castor genus and the Castoridae family, which is part of the Rodentia order. Other groups of mammals in this order include mice, rats, guinea pigs, squirrels and porcupines.

How to identify Eurasian beavers

Compared to their North American cousins, the Eurasian beaver has a larger, squarer head and a longer, narrower muzzle. Where the Eurasian beaver has triangular nasal openings, the North American beaver has square! Generally, Eurasian beavers are slightly larger and heavier than North American beavers.

They have thick, soft brown fur; flat, hairless tails (known as scoops); and webbed feet. They usually measure over a metre from head to tail, similar to a medium-sized dog, such as a labrador.

Beavers are known for their prominent, strong incisors which they use to gnaw the trunks of trees like aspen, willow and yew. Iron impregnates the enamel, giving the teeth their startling orange colour and adding enormous strength. The teeth protrude from their lips to allow beavers to chew underwater. Even strong teeth get worn down by gnawing through trees, so their teeth never stop growing!

How big do beavers get?

Eurasian beavers are the second largest living rodent species in the world (the capybara in South America, is the first). At around one metre in length, the beavers can weigh in at up to a hefty 30kg - roughly equivalent to an 11 year old child!

Following the chance discovery of a 20-inch-long fossil in 2008, scientists have revealed that the largest rodent roamed the earth four million years ago in South America. The Josephoartigasia monesi - a now-extinct relative of the Eurasian beaver, weighed up to two tonnes and was bigger than a bull!

What do Eurasian beavers eat?

Contrary to belief and their portrayal in popular culture, Eurasian beavers are strictly herbivorous and only eat plants. Vast quantities of water and riverbank plants such as brambles, tubers, as well as softwood bark trees like aspen, hazels, willow, cherry and apple, all amount to a daily food intake of about 20% of the beaver’s body weight.

Some research has shown that individual beavers display characteristic preferences for certain plants, such as ivy. This has helped researchers to identify and follow individual beavers in reintroduction trials, such as on the River Otter in Devon.

An army of gut flora and microorganisms assist the lengthy digestive process that follows the beaver’s high cellulose diets; breaking-down the bark into nutritious bacterial proteins.

What predators do Eurasian beavers have?

Across Europe the main predators of Eurasian beavers are red foxes, lynx and eurasian wolves. For the beavers that live in Britain, they are largely protected from predation. However, they can be vulnerable to disturbance from humans and dogs in some habitats, especially during breeding time in spring.

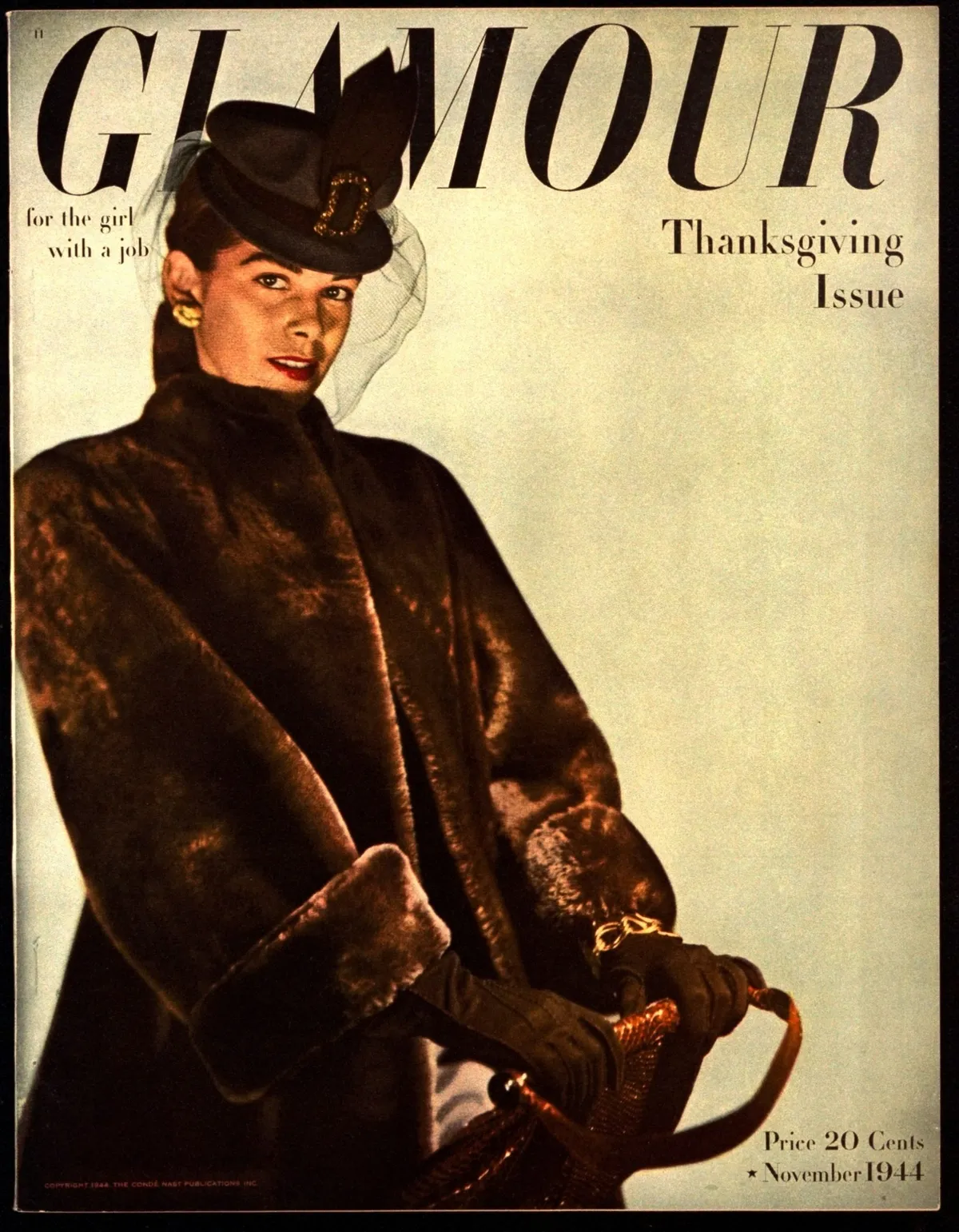

Historically, humans were the main threat for Eurasian beavers. Beavers disappeared from Britain largely due to over-hunting. Beavers were hunted for their rich, lustrous fur which was often made into hats.

Hunters were also interested in their castoreum, a musk-like substance contained in the scent glands of both male and female beavers. The castoreum, which beavers use to mark their territory, was used in perfumes and medicines.

Habitat loss was also a key reason for the beaver’s demise, largely due to farming and deforestation.

How long do Eurasian beavers live for?

The average lifespan of a Eurasian beaver is seven to eight years, but many have been known to live up to 25 years old!

What are baby Eurasian beavers called?

Baby beavers are called kits.

Male and female beavers are monogamous, meaning they usually stay with the same partner for life. Female beavers give birth to between one and four kits per year, with most born in the lodge in May and emerging in late June.

Kits usually stay with their parents for up to two years before leaving the family unit to disperse, find a mate and set up a new family.

Why do Eurasian beavers build dams?

Beaver dams are impressive structures made out of wood, mud and stones. They are constructed by beavers to create suitable living conditions for them and their kits. The dam acts as a first line of defence against predators, by submerging the entrance under around one meter of water and concealing secret tunnels that lead to the main chamber.

A real feat of ‘engineering’ they slow the flow of water, creating new, ‘beaver ponds’, surrounding the lodge which offer safe foraging habitat. Scientists have shown that these pools can provide excellent habitat for fish such as trout and salmon, as well as for several species of amphibians, aquatic invertebrates and water voles. The dams also act as a natural water filter, removing pollutants that leach into the water from farmland - ultimately improving water quality.

Such widespread biodiversity benefits have earned beavers the title of ‘ecosystem engineer’. They are also known a ‘keystone species’, meaning that without it, the surrounding ecosystem would be significantly ‘poorer’, perhaps ceasing to exist altogether. Beavers have a disproportionate influence on the environment and biodiversity around them.

The sound of rushing water triggers the beaver’s instinct to start collecting hardwood, such as oak - and begin building. Mud, rocks and timber are placed methodically across the area of water flow, creating a solid foundation.

Once the skeleton of the dam is in place, more vegetation and sticks are added, before using their forepaws to bind the mud together. Rising water levels indicates the formation of their protective pools, which then prompts a shift from dam building, to lodge building.

Do Eurasian beavers hibernate?

Again, contrary to popular belief, Eurasian beavers do not hibernate. Rather, they are ‘crepuscular’, meaning they take to dawn and dusk to carry out most of their daily activities throughout the year.

Are Eurasian beavers endangered?

Since various reintroduction projects, the Eurasian beaver is now recognised as a native mammal in Scotland and is deemed as ‘endangered’ by the IUCN. The beavers in the rest of the Britain have not been formally recognised as a native population and so have not been assessed by IUCN in the same way. However, increasing numbers of reintroduction trials across key habitats aim to restore stable populations of this amazing mammal.

What is being done to help Eurasian beavers in the UK?

Beaver Trust

Beaver Trust is hosting the Cornwall Beaver Project alongside Cornwall Wildlife Trust, most recently seen on BBC Springwatch 2020. The small but dedicated team are advocating to campaign to make beavers a recognised native mammal in England and across Britain.

Together with key stakeholder voices, they are working towards a national strategy with the Government that aims to champion the value of beavers as climate change mitigators and key allies in reversing biodiversity loss.

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Devon Wildlife Trust

Devon Wildlife Trust has led England’s first licensed unfenced beaver trial, on the River Otter in East Devon. Together with Exeter University, the five-year project since 2015 has been a landmark investigation into the impacts of beavers living on the river, within a productive, agricultural landscape.

With the trial coming to a close this September, the partners have released an extensive ‘Science and Evidence Report’ available for public reading, detailing how the beavers have benefitted people and wildlife.

In August 2020, Defra announced a landmark decision to allow the population of beavers on the River Otter to stay permanently.

Scottish Wildlife Trust

On 24 November 2016, the Scottish Government made the landmark announcement that beavers are to remain in Scotland. This is the first time that a mammal has been formally reintroduced in UK history.

The trial population of beavers remains in Knapdale, and the Scottish Beaver partners are now focussing their efforts on reinforcing this population to ensure its long term future.

Sussex

The Sussex Beaver Project, led by Sussex Wildlife Trust and the Knepp Estate, received approval in early 2020 to reintroduce beavers to a 250 ha fenced area of the Knepp estate in West Sussex. The National Trust also had approval to bring Beavers back to Valewood at Black Down. These are due to occur in autumn 2020 and spring 2021.

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Research

Many British institutions are actively involved in pioneering research around beaver reintroduction and landscape restoration across Britain, such as Exeter University, Plymouth University and Southampton University.

Beaver Trust is a British conservation charity founded in 2019. It is committed to not only bringing beavers back to Britain, but champions working with farmers, local communities and conservationists to restore biodiversity and re-connect landscapes.