The world wasn’t crying out for a turtle-cat hybrid. But the arrival of ‘Turtle-cat’ in 2018 proved such a hit that someone forked out US$25,000 for it. What they paid for wasn’t a new-to-science discovery, a genetic experiment, a toy, or even an astounding work of art, but what is rather catchily known as a ‘non-fungible token’ (NFT).

If you’re lost at the words ‘fungible’ or ‘token’, you’re not alone. NFTs are a bewildering subject. Essentially, they’re a digital trading system.

“Non-fungible tokens are similar to cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin,” explains Peter Howson, senior lecturer in international development at Northumbria University.

“The big difference is that, whereas individual Bitcoins all have the same value and are interchangeable, NFTs are more like antique baseball cards: each has a different value. Fungible means ‘mutually interchangeable’ and ‘of identical value’. Anything digital can be represented as an NFT. They’re crypto-collectibles rather than cryptocurrency. You collect and trade them with other people who share your interest.”

Pete Howson explains the key terms of NFTs below, but for more detailed information, our colleagues on BBC Science Focus have put together an guide on everything you need to know about NFTs.

What are NFTs?

Non-Fungible Tokens are similar to cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, but whereas individual Bitcoins all have the same value and are interchangeable, each NFT has a different value. NFTs exist on your computer as digital representations of artworks, songs, films, event tickets, and games.

What is a blockchain?

A blockchain is a shared electronic database, like a DropBox folder, except you can only add files to it. You can’t change or delete anything already there. There are loads of different blockchains. But most NFT creators use Ethereum, which uses an energy-intensive computer function called ‘mining’. It’s called mining because, like digital gold coins, that’s how new cryptocurrencies are created.

What is mining?

With DropBox your shared folder is looked after by a company for a fee. With a blockchain, there’s no company. Instead, the blockchain uses a global network of millions of ‘mining’ computers that compete to process your data for a fee. They play a game to guess the combination to a long string of digits, with the most powerful winning a few thousand pounds worth of cryptocurrency. The combination changes every 15 seconds and the contest continues forever.

How do NFTs work for wildlife photographers?

“The collector of an NFT owns only a token – a type of digital certificate of ownership. Its value is determined by what someone is willing to pay for it, based on exclusivity and the photographer. The photographer owns the original image copyright and the collector can’t reproduce the image,” wildlife photographer Richard Bernabe.

“Sometimes the photographer will include a print as a nice gesture, or maybe the collector would want to possess the image file (ie JPEG) the token represents. That’s fine, but neither is where the NFT gets its value. Imagine a Manchester United jersey signed by Ronaldo. If he were to sign it and then provide a certificate stating it is the only one he has ever signed, it would be the certificate, not the jersey itself, that is of most value. It’s the same with NFTs.”

Turtle-cat, also known as Honu, was created by online blockchain game CryptoKitties, and was auctioned to raise money for marine conservation. It was a sign of things to come – NFTs now sell for ludicrous sums of money, and are proving a significant source of revenue for charities.

“When this pretty rubbish picture of a turtle-cat sold for US$25,000, people were like: ‘What’s going on?’ It was a mind-blowing sum of money,” says Howson. “But that cryptocurrency went to ocean conservation charities. As long as there have been NFTs, there have been wildlife charities making money from people donating them or giving them the proceeds. Cartoon apes have sold for £700,000, with the money going to an orangutan charity. £500,000 from NFTs also went to Virunga National Park.”

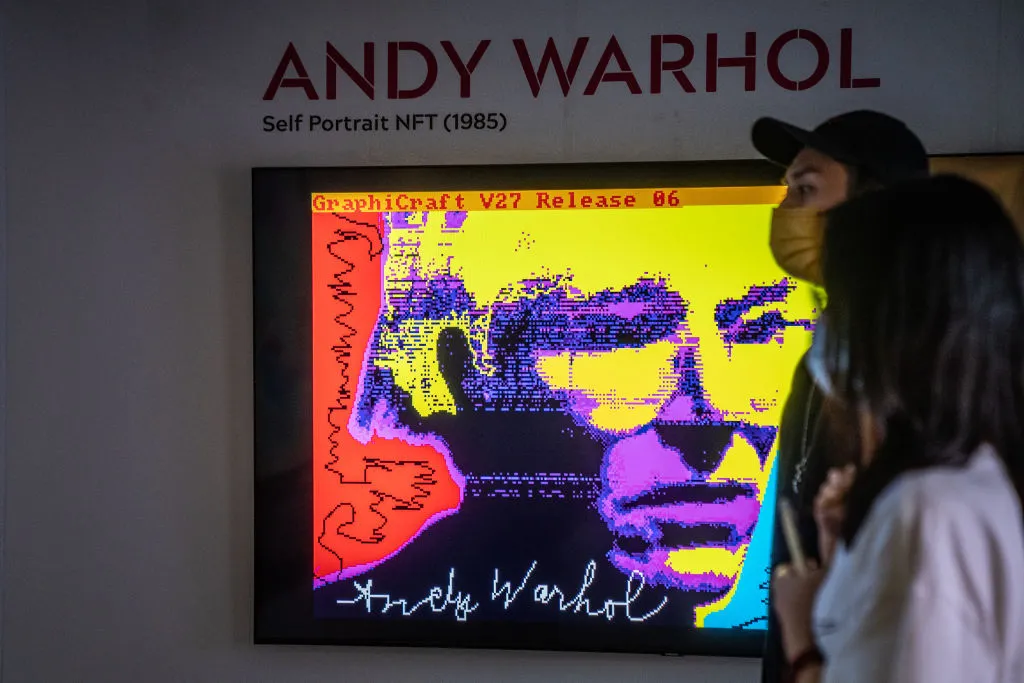

Emerging in 2015, NFTs have ranged from collections of animal drawings, like Pepe the Frog, to a house on Mars (digital, not real) that sold for US$500,000. The value of an NFT isn’t connected to its brilliance, beauty or physical value, so an NFT of a photographic masterpiece isn’t necessarily of higher value than a quirky cartoon. CryptoPunk 7804, for example, a pixelated figure smoking a pipe, sold for US$7.5 million.

The value is instead determined by what people are willing to pay and the NFT’s exclusivity, including how many are minted (published for purchase). “The most expensive NFT so far, The Merge, sold for US$91.8 million in December 2021,” says Howson. “It’s just two grey balls on a black background. You could buy three private jets, or this image of two grey balls. The talent of the artist doesn’t seem to make any difference to the prices NFTs are fetching. A lot of the value is down to buzz among the collectors.”

Who owns an NFT?

And it gets stranger than that. NFTs are often compared to something like a rare baseball card. But with a baseball card, or any memorabilia item, you get to take it home, hold it, display it, look at it. With NFTs, all you usually ‘own’ is a digital receipt.

“It’s like me saying ‘I’ll sell you the Mona Lisa’ but it still has to live in the Louvre in Paris,” says Howson. “You just get to say you own it. You can’t make copies, print it or move it anywhere. When you buy an NFT, you’re buying a certificate of ownership – a receipt file that lives in a ‘crypto-wallet’. The transaction is permanently written onto a blockchain. The creator of the artwork usually retains the actual ‘thing’ – the Tweet, photo, painting or song. In most cases with digital art, you own little more than bragging rights. This is the bizarre world of NFTs.”

We were promised hologram phones and flying cars. Instead, we get a ‘Schrödinger’s cat’ trading system, where you own a thing and don’t own it at the same time.

So, why bother? “For NFT artworks, it’s pure speculation,” says Howson. “As with anything crypto-related, the majority of people buy these digital assets because they expect the value of them to go up in future. NFTs are seen as an investment.”

How do NFTs raise money for endangered species?

The world’s wildlife is in crisis. Charity donations have declined, with people’s livelihoods and earnings hit by the global pandemic, and fundraising events have been cancelled. Older donors, who are more likely to give regularly, are gradually dying out, leaving wildlife charities needing to attract younger supporters. This is where ‘exciting’ tech, such as NFTs, comes in handy.

“With NFTs, we can reach a whole new demographic,” says Tristan Wood, director of wildlife charity Saving The Survivors, which has raised US$7,000 from NFTs. “We’ve had pieces of art donated in the past and artists have shared revenue from sales with us, but with NFTs, you have a global accessibility and you can present works to your audience at speed.”

Smart Contracts – rules on transactions, written into the code – are a big part of NFTs’ appeal. They often offer a 10% resale royalty, so individuals or organisations keep earning as the NFT is traded.

NFTs can also raise awareness. People could display their NFTs as profile pictures on social media, to act as ambassadors for wildlife charities. They could also keep the digital artwork or have it printed on a mug or T-shirt.

Wildlife photographer Richard Bernabe is one of many who have delved into NFTs, including a newly minted Living Legacies collection of black-and-white African wildlife images with 15% of proceeds going to wildlife conservation organisations, including African Wildlife Foundation, Born Free Foundation and WildAid.

“My experience with NFTs has been extremely positive,” he says. “When I realised my photography could be tokenised as NFTs and collectors could invest in me directly, without the traditional intermediaries and barriers of gallery curators, brokers, managers and agents, I knew I was seeing into the future. There’s a genuine spirit of community among photographers, artists, and collectors, and we all seem to realise we’re at the very beginning of what will soon be truly big. Of course, we could all be wrong. This could end up being a fad or bubble that bursts tomorrow. But I don’t think so.”

What are the risks with NFTs?

Part of the appeal of NFTs, Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies is that they’re decentralised, existing outside the regulations of international banks or governments. That brings benefits and risks. “With any crypto instrument, they’re a bit scammy,” says Howson. “People like Damien Hirst, Paris Hilton and Elon Musk all sell NFTs, but there’s often no way of knowing who is legit and who isn’t.”

An NFT creator or curator could also say they’re giving the proceeds to charity, but it might not be true. “If a charity has curated a collection of NFTs, you should go direct to the charity and they’ll point you to where you can buy them,” advises Howson.

These aren’t the only risks. “We’re actually seeing very few NFTs resell for more than what the original buyer paid,” Howson adds. “‘Normal people’ should definitely not see them as an alternative to a pension plan. But who knows? In 100 years, maybe they’ll be worth millions, like super-rare stamps.”

Are NFTs bad for the environment?

Yet there is what Peter Howson calls an “intolerable contradiction” at the heart of NFTs being used by wildlife and environmental charities. Creating NFTs is incredibly damaging to the environment, meaning charities are contributing to the destruction of the very natural world they’re working to protect.

“The climate change aspect needs to be looked at,” argues Howson. “Blockchains like Ethereum, which most NFTs are minted on, use an immense amount of energy, requiring millions of ‘mining’ computers around the world that compile and verify transactions. Ethereum uses more energy annually than the Netherlands. The blockchain has a carbon footprint larger than Sweden’s – around 50 million tonnes of CO2. Each individual NFT is responsible for 115.07kg of CO2 per transaction. If you watched 20,000 hours of YouTube, you’d generate less CO2 than if you bought or sold an NFT once.”

Organisations such as Greenpeace have rejected working with NFTs or accepting donations in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies on energy-consumption grounds. “Most ordinary people are becoming more aware of the environmental and social impact of NFTs, and are starting to question it,” suggests Howson. “This is why we’re seeing some charities pulling out of this space, and also governments and countries, like Iceland and Kosovo, regulating it more and making it illegal on environmental grounds.”

International Animal Rescue, who raised more than US$50,000 in its first month of using NFTs in 2021 and were aiming to raise a further US$500,000 through an NFT partnership, has changed its policy largely due to environmental concerns, no longer accepting crypto donations and concluding all relationships with NFT projects. “The potential for blockchain technology is vast, as is the potential for fundraising,” says a spokesperson, “but the technology needs to be more aligned with our values.”

The environmental impact presents a serious problem that could strangle NFT use for conservation. However, less energy-intensive blockchains do exist, and there’s plenty of time to reform NFTs. “With Bitcoin, Ethereum and Litecoin, people didn’t give a damn about the environmental impact – they just wanted to make money,” says Howson.

“But if you bring in people who care about the environment and wildlife, they put pressure on Ethereum and others to make those platforms more energy-efficient and environmentally sustainable. If NFTs are going to survive, they’ll have to become more sustainable. Otherwise people will just stop using them.”

Wildlife charities are trying to address these environmental concerns. WWF’s recent Non-Fungible Animals or NFAs were created on Polygon, which is described as a “sustainable, eco-friendly blockchain”.

But the idea of ‘Green NFTs’ that use more sustainable blockchains only tells part of the story. “Even if you use a more sustainable blockchain platform to buy and sell NFTs, people are still going to pay for them using Bitcoin and Ethereum, which are energy-intensive, with a massive carbon footprint,” explains Howson. “If you’re involved in NFTs, you can’t avoid getting your hands dirty.”

There are other negative impacts that need consideration too. “An enormous amount of electronic waste is caused by NFT and crypto platforms,” Howson explains. “Piles of computer parts, graphics cards, machines and memory drives getting burned out and dumped in the global south, in India or China, where hazardous electronic waste is picked through by the poorest people in the world. Every transaction is the equivalent of throwing away two iPhones.”

What's the future for NFTs?

Will NFTs die out, or will they evolve and thrive? The future’s hard to predict. But you can expect the unexpected.

“We’re seeing digital representations of rare wildlife, like platypuses, being sold as NFTs for use in metaverse gaming to raise awareness of the plight of platypuses in Australia,” says Howson.

“We’re starting to see carbon credits traded as NFTs. Just when you think wildlife fundraising has got as weird as it can possibly get, someone pays millions for a digital pair of socks for their rare metaverse panda avatar, or something. That’s just a normal day in the world of NFTs.”