There’s a touch of fantasy about the Odonata – the group of insects that includes dragon- and damselflies. Glimpsed on a golden summer evening they might almost be fairies, and their iridescent eyes and enamel-coloured bodies gleam like jewels.

These are exciting times to study dragonflies and damselflies. Climate change has brought a steady flow of new species to our shores from the Continent, including the willow emerald and small red-eyed damselfly. Many of our resident species have also increased their ranges – emperors, black-tailed skimmers and ruddy darters are all rapidly heading north,

There’s no shortage of identification guides and regional atlases to these insects. Glittering in the summer sunshine as they cruise the still waters of a pond, many species can be identified in flight or at rest. Keep a close eye out for identification features, such as the markings on the thorax or the abdominal segments, and don’t forget to make a note of where you spot your subjects – habitat can often be a useful clue.

If you don’t have an insect guide to hand, a photo snapped while the insect rests will aid later identification: all of our common species have distinctive markings. If possible, it's a good idea to take photos from different angles to maximise the chance of getting its identification right.

As you learn more about them, dragonflies become individualists: emperors for example, hardly need to settle.

Males and females are often distinctly coloured or patterned, though beware of newly emerged ‘teneral’ adults, which are pale shadows of the mature insects. We’ve illustrated males here, but describe the differences in females.

How to tell the difference between dragonflies and damselflies

Like all insects, both ‘dragons’ and ‘damsels’ have six legs and a body divided into head, thorax and abdomen.

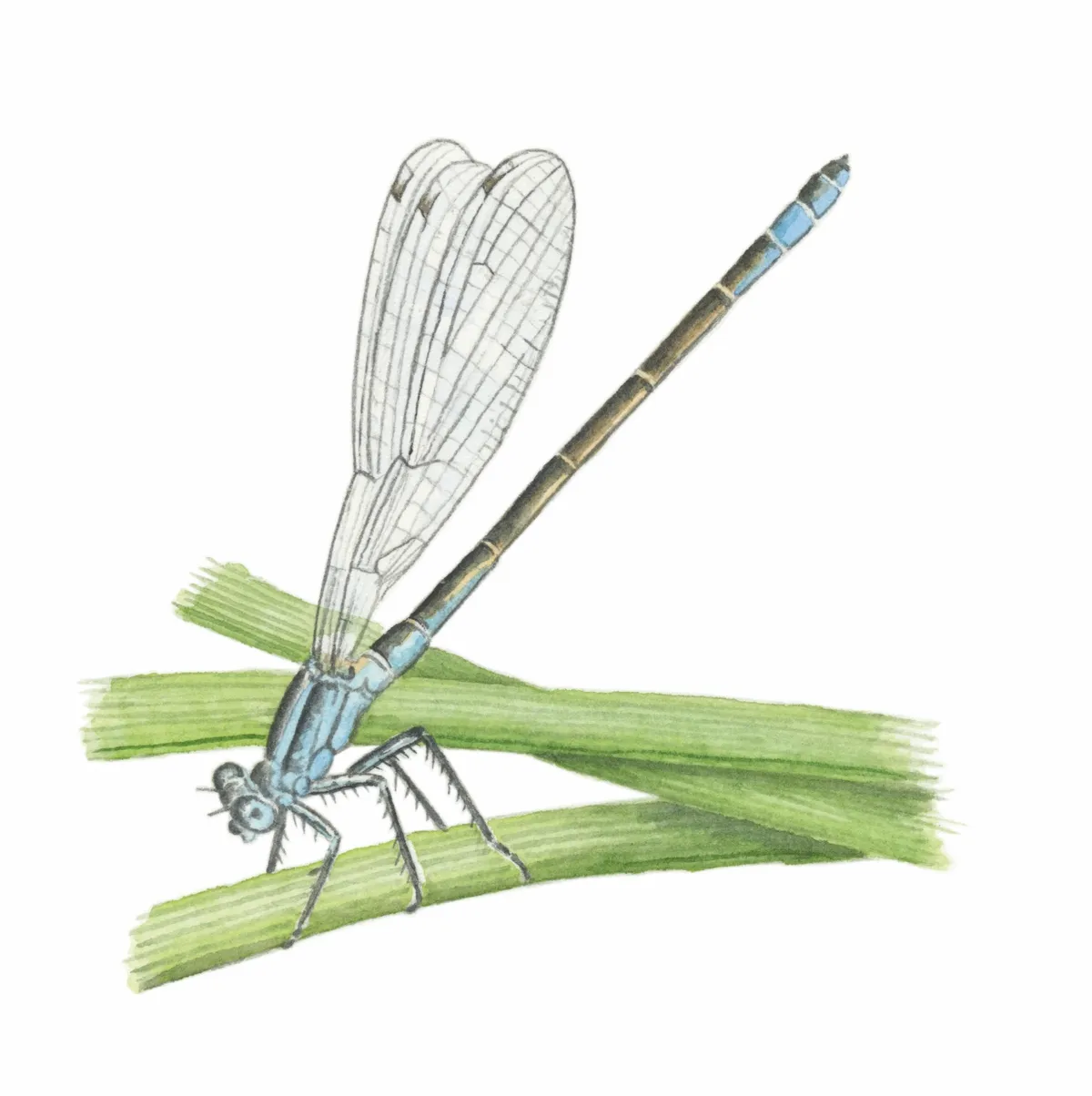

It's possible to tell the difference between the two. As a rule of thumb, damselflies are mostly small and slender, resting with their wings folded along the body, while the larger, more robust dragonflies always hold their wings roughly perpendicular to their body.

How do dragonfly larvae hunt?

Dragon and damselfly larvae are fierce predators. Though they will chase down their prey, they are particularly well adapted to ambush hunting. An individual lies in wait, using its excellent eyesight and sensitive, hair-like structures on its legs and antennae, known as mechanoreceptors, to detect a passing meal.

When lunch approaches, it engages its labium – a specialised prehensile structure unique to this group that is folded up beneath the head when at rest and held in place using a locking mechanism. Internal hydraulic pressure – created by contraction of the abdominal muscles and closure of the anal valve – releases this mechanism and allows the labium to fire. This lethal appendage can fully extend in as little as 15 milliseconds, giving the victim no time to react.

A pair of pincers at its tip grab the prey and draw it into the mouth, where it is swifty chewed by the powerful serrated mandibles that give Odonata their name – ‘toothed jaw’.

This Q&A originally appeared in BBC Wildlife and was answered by Christina Harrison.

How to identify dragonflies

Broad-bodied chaser (Libellula depressa)

The male has a broad and light blue abdomen with yellow spots down each side, where the female and immature adults are golden-brown in colour on the abdomen, with paler spots. All have dark brown wing bases. The species is relatively common in southern and central England, and Wales. It is becoming more common in northern England and can be found at a few sites in Scotland.

It can be seen around ponds, lakes and sometimes gardens from May to July (sometimes August), and can be one of the first dragonfly species to colonise a new pond. After flights looking for insects or after being disturbed, it will often return to the same perch. Mating occurs during flight, and the female will oviposit onto vegetation below the water surface.

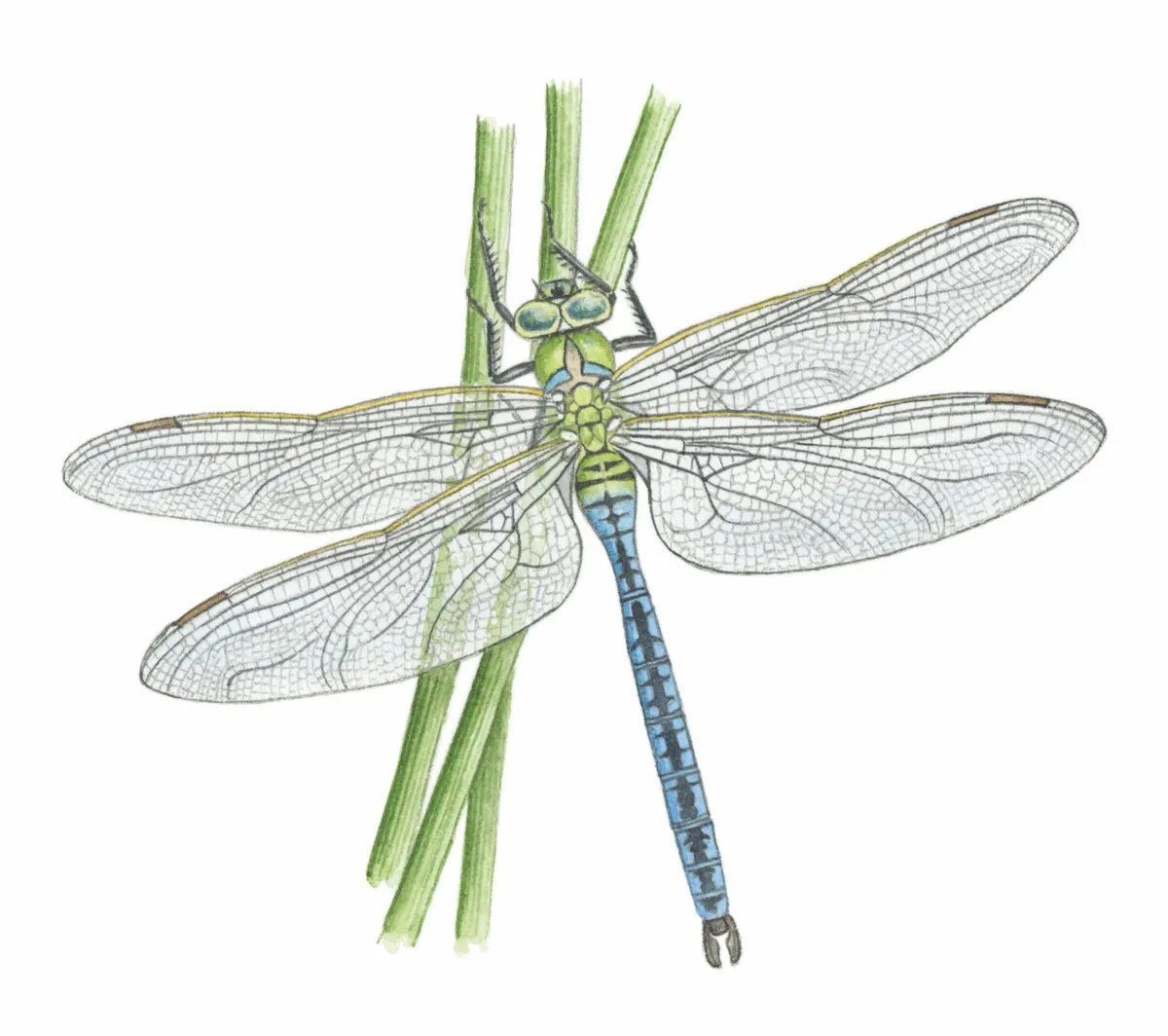

Southern hawker (Aeshna cyanea)

The males of this species are usually dark, with blue-and-green markings, whereas the females tend to be brown with green markings. They have become increasingly common in most southern regions of England and Wales, and should be quite easy to see, thanks to the fact that they are highly inquisitive and will often come close to humans.

You'll often find them in garden ponds, as they breed in well-vegetated, small ponds, before hunting in woodlands in the evening.

Four spotted chaser (Libellula quadrimaculata)

Both male and female four-spotted chaser dragonflies are uniformly brown across their bodies, with a yellow wing-base and two dark spots on the leading edge of each wing. It is these wing markings that distinguish them from other chaser dragonflies. They're found throughout Britain, usually at the edges of shallow ponds and lakes.

Emperor dragonfly (Anax imperator)

This is one of Britain's largest dragonflies, growing to about 78mm. Males have a unique sky-blue abdomen, while females have a green abdomen, both with a central dark line running through. Their bodies are matched by green or blue eyes, and you'll rarely see them settle. They’re constantly on the move, usually based around large, well-vegetated ponds and lakes. You might also spot them around canals.

How to identify damselflies

Common blue damselfly (Enallagma cyathigerum)

The male common blue damselfly is black and blue, while the female is black and either blue or a dull green. Their markings differ slightly, with males tending to have a mushroom-shaped mark below their wing base and females having more of a thistle-shaped mark in the same place. They frequent open water more than other blue damselflies.

Azure damselfly (Coenagrion puella)

This is a common, widespread species of damselfly throughout England, Wales and the lowlands of south and central Scotland. Both males and females have a pattern of black and bright colours – blue for the males, green for the females. The males have a unique 'U' shaped marking below the base of their wings. They're usually found around small ponds and streams, or the edges of larger bodies of water.

Blue-tailed damselfly (Ischnura elegans)

Slightly more difficult to spot, the blue-tailed damselfly is small (about 31mm) and dark, with a light spot located near the end of the abdomen. The male's spot is always light blue, whereas the female's varies between at least five different colours. It is a hardy creature, surviving in lowland habitats including polluted water, where often it will be the only species in existence.

Large red damselfly (Pyrrhosoma nymphula)

The most common of all red damselflies, these are red and black – though the females have some additional yellow markings. They avoid fast-flowing water but can be found across the entirety of Britain, and are fairly common.

Banded demoiselle (Calopteryx splendens)

One of the more visually impressive damselflies, the banded demoiselle has large, butterfly-like wings. Both males and females have metallic bodies, but males tend to be blue, while females are green. Males have dark blue/black spots across their wings, but females’ wings are translucent pale green. You'll usually find them along slow-flowing rivers, particularly those with muddy bottoms. In recent years, its range has expanded, growing beyond Wales and England into Scotland.

What do dragonfly and damselfly nymphs look like?

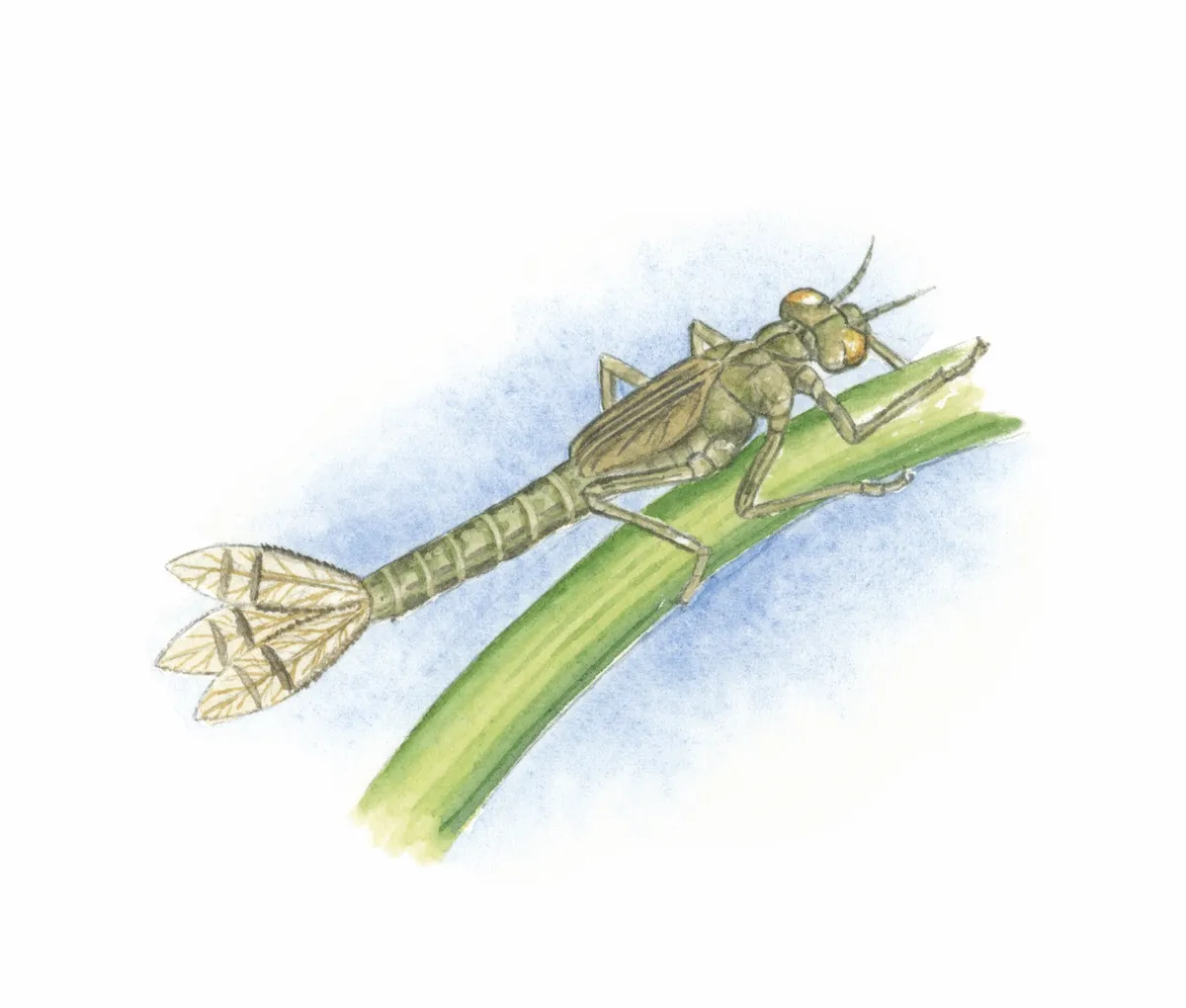

The juvenile stages of dragonflies and damselflies are called nymphs, and live underwater hunting down and eating live prey such as other insect larvae, leeches, tadpoles and small fish.

The time for larval development (from hatching out of an egg to emerging as an adult) can vary between species, typically taking between one to two years. However some species are more rapid (between two to three months in emerald damselflies and more than five years in golden-ringed dragonflies).

Dragonfly nymphs have wider abdomens, and damselfly nymphs can be identified by the three fin-like structures at the end of their abdomen, known as caudal lamellae. Some other insect nymphs also have similar structures, including mayfly nymphs and stonefly nymphs.

When the nymphs of dragonflies and damselflies are ready to moult, they climb up emergent vegetation and push their body outside of their larval skin. The wings and abdomen expand and harden, and once ready, the adult will fly. The maiden flight is typically weak and only over a short distance, and they are particularly vulnerable to predation at this time, to predators such as hobbies. Newly emerged dragonflies and damselflies are known as tenerals, and during this stage they are much paler in colour and hard to identify to species level.

The final larval skin of the nymph is left behind on the vegetation and is known as an exhuvia.

Main image: A four-spotted chaser dragonfly. © Sander Meertins/Getty

All illustrations by Felicity Rose Cole.