About the photographer

Stefan Christmann is a nature photographer and filmmaker from Germany. He was part of the team that planned and filmed the emperor penguins episode for BBC's Dynasties.

His unique images of Antarctica and of the emperor penguin colony of Atka Bay have been published in National Geographic and BBC Wildlife Magazine, as well as in many other publications worldwide. They also won the NHM Wildlife Photographer of the Year Portfolio Award in 2019.

With the poetry of his pictures and his emotional stories, Christmann wants to reveal the special beauty of the polar regions and support their much-needed protection.

About the book

A book eight years in the making: when Stefan Christmann first wintered in Antarctica in 2012, he fell in love with the neighbours of his research base: the 10,000 emperor penguins of Atka Bay.

In personal narrations from two over-winterings, Christmann tells stories from the everyday life of the animals: of life and survival, of birth, love and companionship at the end of the world.

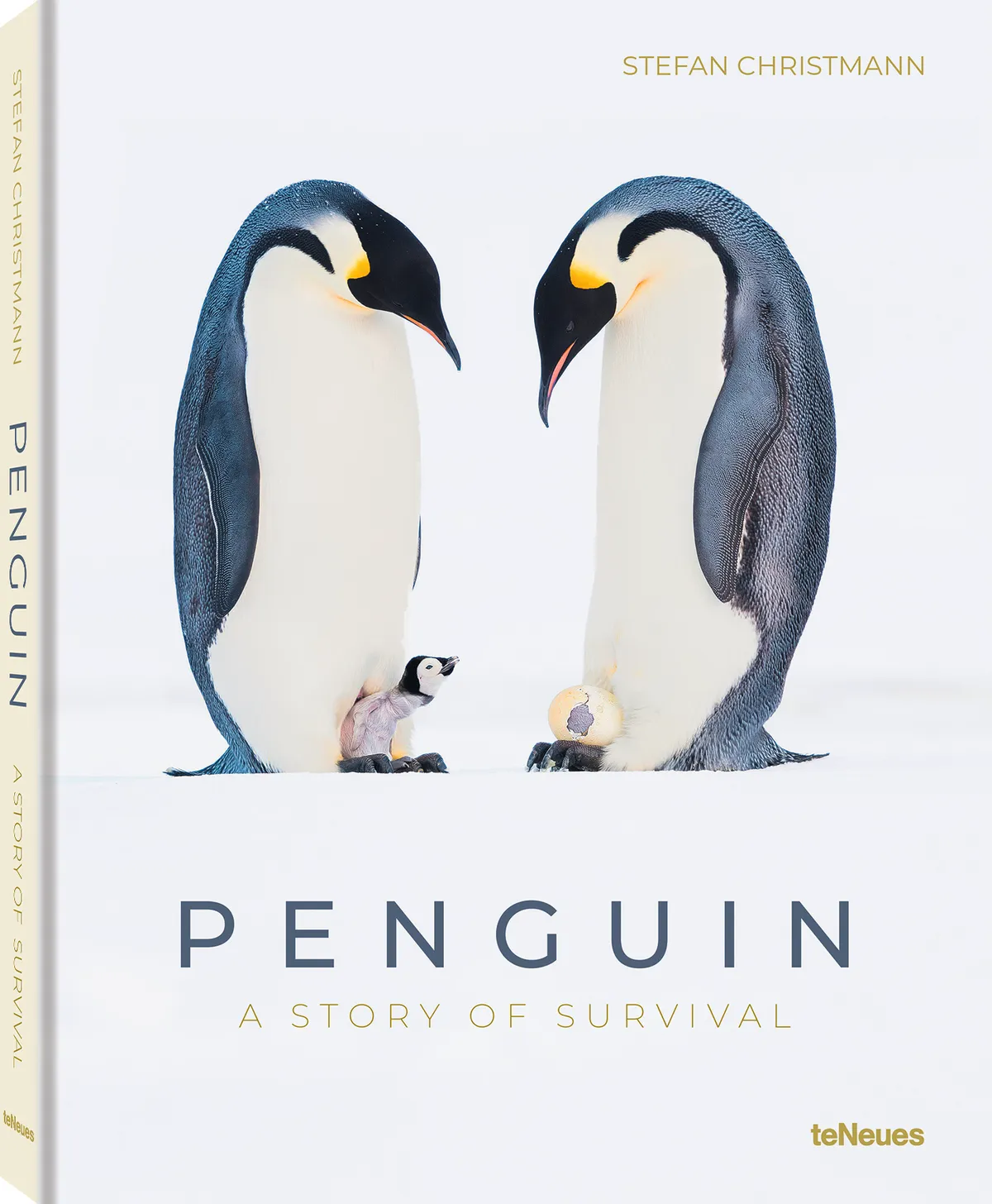

Penguin: A Story of Survival portrays Antarctica’s most iconic bird, which can neither fly nor run, but still manages to create a home in one of the most hostile habitats on Earth.

To view the images as a slideshow, click on the arrows in the top right hand corner of the photos below.

Musical notation:

An emperor penguin couple's unique song is their musical key to finding each other amongst thousands of other birds in the colony. When they return from foraging in the open ocean, they will call out for their mate upon arrival. On very cold days, their warm breath will paint this characteristic melody into the air like the scores of a musical notation.

An Uncertain Farewell:

After the female has laid her egg and successfully passed it on to the male, it is time for her to leave the colony. She desperately needs to feed and refuel her depleted energy reserves. During the early stages of egg-laying, many females will start their long hike to the ocean all by themselves. While their journey will be lonely and cold, at least they know that they have a head start into the breeding cycle.

The Playdate:

One behaviour of emperor penguins which is not fully understood up to this day are "playdates" for the chicks, which are arranged by the parents. Usually two adults, with chicks on their feet, will stand right in front of each other and constantly lift their brood pouches. The chicks usually start interacting with each other, calling and reaching for their peers on the other side. The parents will sometimes stand so close to each other that their chests touch and they can rest against each other. This behaviour led Stefan to come up with the godparent theory that is also explained in the book.

Mini Huddle:

The strategy of huddling is a behaviour that has to be learned by the young penguin chicks early on in their lives. It is one of the cutest things I have ever seen. Despite their parents being extremely calm and organized while huddling, the young ones try to take shortcuts into the warm centre by crowd-surfing over their peers. Sooner or later, however, they will understand that everybody gets to be in the warm centre, even if those waiting in line.

The Huddle:

The huddle is the emperor penguins' secret weapon against the cold and their ultimate survival strategy. Working as a giant incubator, the birds will stand close to each other with their heads tucked between the shoulders of the birds in front of them. Sharing their dissipated body heat, temperature can reach up to 37°C in the centre of the huddle.

Welcoming Committee:

Even when the penguins are huddling and conserving their energy on a cold Antarctic winter day, there is always the odd one out who is already warm enough. Many times, these individuals broke away from the colony and welcomed us as we carefully approached from afar. We always considered them to be our welcoming committee.

First Surfing Lesson:

Emperor penguins are designed for many things, but when it comes to mating it becomes quite obvious that balancing is not their strong suit. When the male steps onto the back of the female just before copulation, he struggles to find a safe stance; resembling someone taking their very first surfing lesson.

The Egg:

Emperor penguins don't build any nests and hence must carefully balance the fragile egg on the backs of their feet. Finally, they will put their brood pouch over it, in order to keep it warm and shielded from the elements. With every step they take, they rotate the egg on their feet a tiny bit, to evenly warm it from all sides.

The Return:

Late March to early April is the time when the emperor penguins return from the open ocean and make their way back to their breeding grounds. The newly-formed sea ice is covered with pressure ridges at that time, which resembles an obstacle parcourse for the returning birds. Until they reach the southern part of the bay, they have to travel around 10 kilometres.

The Plunge:

Emperor penguins normally breed on the sea ice, but its increasing destabilization over the past decades oftentimes forces them to finish their annual moult on the more stable ice shelf. When it is time for them to return to the ocean, they must take risky leaps from steep ice cliffs. While this looks spectacular, in reality, it is a behaviour that should not exist.

Trapped on the Ice Shelf

Just like adult emperor penguins, emperor chicks have to undergo their moult at the end of the breeding cycle. In their case, this change of plumage is of even greater existential importance; without their black and white penguin tuxedo, they would not be able to swim in the ocean. If the sea ice breaks open too early, they must climb onto the stable ice shelf and hope that they can finish their moult before they eventually starve.

The Drop

Each breeding cycle, emperor penguins lay a single egg per breeding pair and they focus all their efforts on hatching it. Rarely captured on camera, the female lays her egg. She cleverly positions her feet to ensure that she can immediately pick up the warm, steaming egg as soon as it drops onto the frozen, rock-solid sea ice.