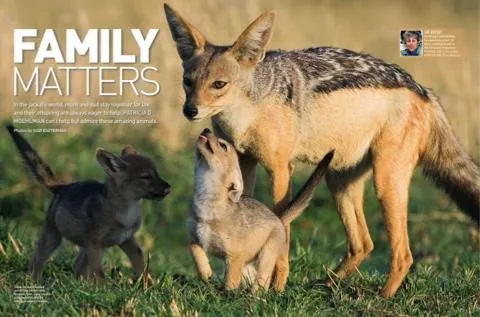

A black-backed jackal (or silver-backed jackal) in the grassland of the Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya © Wolfgang Kaehler / LightRocket / Getty

The gritty 1973 thriller about an assassin plotting to murder the French president has much to answer for. Almost 40 years on, The Day of the Jackal continues to cast a long shadow over the lives of the wonderful animals that gave the film’s villain his codename. The word ‘jackal’ still invokes images of scavengers and terrorists, yet these stereotypes are far from the truth.

In fact, jackals make admirable role models. They lead a social, co-operative existence. The members of each family display loyalty, courage and generosity – traits that humans revere.

Above all, the adults form stable pair bonds. Monogamy is relatively unusual in the animal kingdom as a whole, and among mammals in particular, though it is common in the Canidae – the family that includes jackals, foxes, coyotes, wolves and African wild dogs.

But why? What are the benefits of forming lasting relationships? This was one of my first questions when I began studying jackals in the Serengeti.

Scorpio and Libra

My chosen subjects were silver-backed jackals. (Most books and websites insist on calling them “black-backed”, which has always struck me as odd, given that their beautiful grizzled upperparts are so striking.)

Every day I would get up before dawn to search for these small, fleet-footed carnivores. They have an uncanny ability to blend into the savannah woodlands, so, to gain an insight into jackal family life, I started following a male and female, who I christened Scorpio and Libra.

When I first encountered the pair, Libra had six newborn pups, and for the first three weeks Scorpio brought her food in the den. As soon as he arrived she would lick his muzzle, prompting him to regurgitate the contents of his stomach (usually grass rats). This enabled Libra to stay with the pups and nurse them at regular intervals.

I later discovered that Scorpio also fed his mate during her pregnancy, so that, in their own way, both parents provided food for their offspring from the time of conception.

Sex differences

Scorpio and Libra’s roles had symmetry and equality. They both marked and defended their home territory, and they groomed each other, hunted together and shared food. But there were differences in what they considered most threatening to the stability of their home and family.

Scorpio would chase away rival males, but did not seem to mind intruding females. Libra was the exact opposite. She immediately saw off female trespassers while Scorpio merely watched.

I was struck by how much energy they put into their relationship. Pairs of jackals stay together for at least five years, which may constitute a lifetime bond, so it is clearly well worth the effort.

Raising a family

Scorpio and Libra had chosen the best time to have a family: the Serengeti’s dry season (June–August), which is when the rodents that form the bulk of their diet are most abundant. Like domestic dogs, jackal pups are born blind and without teeth. The youngsters’ eyes open after about 10 days, and they acquire their sharp puppy teeth at roughly the same time. It is vital that their mother stays in the den with them throughout the first few weeks to provide them with warmth, milk and protection.

At this stage, the young jackals begin to venture out into the open and slowly start to explore their surroundings. They move clumsily at first, but somehow manage to make a headlong dash for the burrow entrance whenever the ‘pup-sitting’ parent gives a warning yowl.

I was entranced by the sight of Scorpio and Libra fearlessly chasing much larger spotted hyenas away from their vulnerable offspring, while yowling and biting the animals’ rumps.

Black-backed jackal mother with pup in Tanzania © Wolfgang Kaehler / LightRocket / Getty

It's playtime

Jackal puppies spend hours playing with each other. Stalking, pouncing, wrestling and games of tag help them to develop the muscles and skills needed for survival in adult life.

When playtime is finally over, they sprawl beside the den, waiting impatiently for their parents to return from their hunting trip with full stomachs. The excited pups then rush to meet them, their tails wagging and their entire bodies wriggling with delight, before licking the adults’ noses to beg for a regurgitated supper.

Scorpio and Libra were sharing their territory with two other adults: a young male whom I named Orion, and a young female, Tamu. Both of them were studiously submissive, always greeting the ‘top dogs’ with heads down, low body postures and much tail wagging.

Often the subordinate jackals would lie belly-up in front of their superiors, and this would be rewarded with a grooming session from the older pair. But who were Orion and Tamu, and what were their roles in this family?

Two plus two

It was immediately apparent that the two young adults were a huge help to Scorpio and Libra. They offered food to Libra while she was lactating and to the pups when they left the den, and chased off hyenas that came too close for comfort.

Their presence also meant that Scorpio and Libra could leave the pups to forage further afield. Research has shown that two jackals are much more successful at bringing down gazelle fawns than single adults hunting on their own.

I suspected that Orion and Tamu were probably the grown-up offspring from the litter that Scorpio and Libra had the previous year. My subsequent research confirmed this hunch: jackals tend to stay with their parents to help raise the next litter.

But a young adult is able to reproduce at the age of 11 months, so why did these two individuals stay put rather than leave to find partners and start new families of their own?

Living off mum and dad

One reason is that it is difficult for young jackals to win territories and mates. By remaining with their parents, they can enjoy the benefits of living in a secure and stable environment – a bit like twentysomething humans who have yet to leave the family home.

For instance, when I followed Orion, I noticed that he often ventured beyond the boundaries of his family’s usual range. Perhaps he was searching for somewhere he could settle, or a potential partner. But the neighbouring territorial males would send him packing and he would flee with his tail between his legs.

So, for several months, both he and Tamu stayed on their natal territory, romped with their younger siblings, groomed them, protected them from hyenas and brought them food.

Young jackals that stay at home for an extra six months may also pick up important life skills, such as hunting techniques and how to evade predators and care for pups. In my study, most individuals that lingered to help their parents left when they were about 18 months old, by which time they had gained valuable maturity and expertise.

I also found that a family’s helpers might be all-male, all-female or a mixture of both sexes, and that there could be as many as three of them.

A young black-backed jackal pup in Tanzania © Wolfgang Kaehler / LightRocket / Getty

Faithful friends

I still need to explain why jackals are strictly monogamous. The answer lies in these startling statistics: though a female may give birth to up to nine pups, a breeding pair raises an average of just one pup per litter to adulthood.

So dad’s contributions are critical: if he does not devote all of his time and energy to the family, no pups survive. Only males and females with a total commitment to one another will rear young successfully.

Jackal families with helpers provide a further twist to the tale, as more of their pups survive – sometimes up to six. Subadults who help their parents to care for younger siblings also benefit from this arrangement.

Since a paired male and female mate for life, all of their litters from one year to the next comprise full brothers and sisters, and this means that helpers such as Orion and Tamu are as closely related to their younger siblings as they would be to their own future pups. Thus they have a compelling reason to hang around – they are furthering their own genes.

Kinship ties are everything to a silver-backed jackal, whose life revolves around its immediate family. The species offers a fascinating glimpse into the way in which monogamy and the co-operative care of offspring evolved, and perhaps can even provide us with a better understanding of aspects of our own behaviour.

Strengthening relationships

For a dog, how many young you can have influences who you mate with.

- The larger the litter, the more help an adult female needs to raise her offspring. This statement may sound obvious, but it forms the basis of much social behaviour in jackals and other wild dogs around the world.

- Smaller dog species such as foxes often have small litters, so the females are usually less dependent on the contributions of the males for the survival of their pups. In these species, there is a tendency towards polygyny: one male breeding with several females.

- But in a medium-sized species such as the silver-backed jackal, the larger average litter size and the relative cost of providing sufficient food for all of the young mean that the male’s role is critical. Therefore, monogamy and strong, long-term pair bonds have a selective advantage for pup survival.

- In larger species, such as the African wild dog (below), which may have as many as 16 pups per litter, an adult pair usually cannot raise the entire brood alone. Though this species may be monogamous, there can be a tendency towards polyandry, where one female is partnered with two or three males. They form large, stable social groups whose members hunt co-operatively and share the task of rearing large litters.

African wild dog pups in Botswana © Wolfgang Kaehler / LightRocket / Getty

Dogs’ dinners

Within the dog family (Canidae), larger species tend to tackle bigger prey and live in bigger social groups.

- One of the smallest canids is Blanford’s fox, which weighs about 1kg and lives in the deserts and steppes of the Middle East and Central Asia. It forages alone, mostly on invertebrates and fruit.

- By contrast, the grey wolf is 40 times heavier and hunts in packs to bring down prey as large as moose.

- Medium-sized canids such as jackals hunt alone or in pairs, and usually have a very varied diet.

The article originally appeared in BBC Wildlife Magazine.