The Netflix documentary Tiger King became a smash hit thanks to wild storylines and interpersonal drama, and this year's follow-up Tiger King 2 already has viewers hooked as the human dramas within the series continue.

However, the series has largely ignored the myriad issues affecting captive big cats in the United States. Even after it was revealed that Joseph Maldonado-Passage, aka Joe Exotic, killed five tigers while running the Greater Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park, very little was said about why the desire to own big cats is so pervasive in American culture.

Here, we delve into the privately-run big cat trade in the US, including why lax regulations have led to animals being treated as a commodity.

US federal law and captive big cats

There is currently no federal law regulating the private possession of big cats in the US, and while the majority of US states have banned the practice, some require a permit and several have no limitations whatsoever for keeping tigers, lions, leopards, jaguars, cougars, cheetahs and hybrids like ligers as ‘pets’. Laws for exhibition also vary in each of the 50 US states, but with far fewer restrictions.

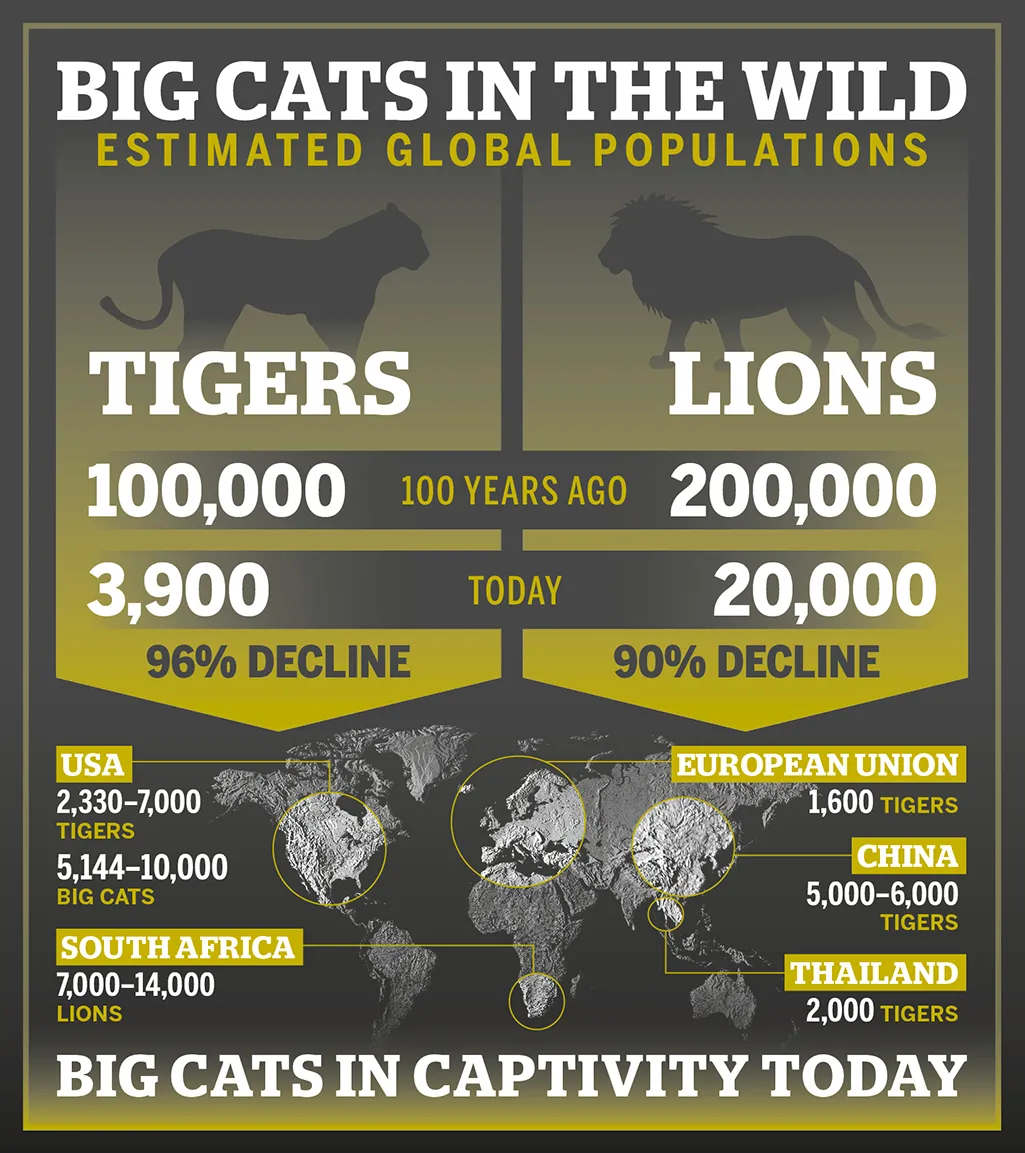

As long as an individual obtains a Class C exhibitor license from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), they are free to use animals for any number of commercial purposes. Not only does this patchwork of state laws create an opportunity for big cats to be exploited, abused and illegally traded across state lines, but the lack of federal regulation makes it easy for them to be treated as a commodity – and impossible to track their populations. Various wildlife organisations estimate the number of captive big cats in the US to be between 5,000–10,000, with the captive tiger population in the US estimated to be between 2,330 and 7,000.

Learn more about lions and tigers:

Although the USDA has specifications regarding the handling of big cat cubs, cub petting is legal as long as the animals are between 8 and 12 weeks of age. Myrtle Beach Safari, which is featured in Tiger King, offers a variety of cub interaction tours at their South Carolina facilities, ranging from a quick photo opportunity priced at $100 to swimming with tigers, which starts at $5,000. With a narrow window for big cat cubs to be handled legally, hundreds are bred each year across the US to create a steady supply for customers, many of whom are unaware of the dark side of this lucrative industry.

Some cub petting venues claim to help rapidly declining wild populations, thus taking advantage of big cat enthusiasts who may not have done their research before visiting. Myrtle Beach Safari founder and director Bhagavan “Doc” Antle even went as far as establishing The Rare Species Fund, a nonprofit that claims to “provide funding to critical on the ground international wildlife conservation programmes.”

However, the Myrtle Beach Sun News recently obtained the 501(c)(3)’s tax documents from 2014 through 2018, and the publication reports that the majority of the nonprofit’s funds are used for on-site animal care, rather than supporting global conservation programmes. This was not mentioned in Tiger King, though the series did note that Myrtle Beach Safari was raided in December 2019 by authorities.

Beyond misleading marketing, most petting zoos offer very little educational information about big cats, enabling them to pass off exploitation as conservation. In the wild, big cat cubs remain with their mothers for up to two years, but cubs bred for petting are separated from their mothers shortly after birth. Many big cats are forced to speed breed and produce cubs five times faster than they would in the wild, and some cubs have even been starved in a bid to stunt their growth.

When cubs grow too large to be handled by the public, some end up in accredited zoos and sanctuaries, but most endure poor living conditions in backyards and unaccredited facilities, lacking proper nutrition, housing and veterinary care. Worse yet, some disappear, and with the loopholes in current US legislation and a lack of records, it is impossible to know where they go.

Lions, tigers and selfies

Beyond lax laws, the desire to interact with these animals and document the experience has increased with the rise of social media. Myrtle Beach Safari regularly posts photos and videos of “Doc” Antle and his son Kody Antle cuddling, feeding and swimming with big cats on Instagram, and the younger Antle shares the same content on his own Instagram and TikTok accounts, which have two million and 14 million followers, respectively. BBC Wildlife approached “Doc” Antle for a comment but he did not respond.

Carson Barylak, campaigns manager at the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), was asked about the role of social media in the big cat breeding industry: “The proliferation of tiger selfies on social media platforms has reinforced demand for cub-handling opportunities in the US and abroad and, especially in the case of public figures, has glamorised private ownership of dangerous felids.”

When interaction with big cats is marketed to an audience of millions, it only encourages people to seek these experiences all over the world, sometimes in countries with fewer regulations than the United States.

“Unregulated captive breeding of wild cats and the petting zoo industry in the US undermines efforts to stop the black market trade in tiger parts, which is driving the decline of tigers in the wild,” explains Dr John Goodrich, chief scientist and tiger programme director for conservation organisation Panthera. While wild tiger parts are preferred for traditional Asian medicine, these majestic felids are also farmed for human consumption, often under the guise of tourism and volunteer programmes.

The most notable example of a tourist attraction doubling as an alleged trafficking operation is Thailand’s Tiger Temple, which was shut down in 2016 after authorities found 40 dead tiger cubs in the facility’s freezer, plus tiger parts and products on site. Other big cat species are on the menu as well. “As tigers become more and more scarce, poachers have set their scopes on wild lions and other big cats including jaguars and leopards,” Dr Goodrich says.

Captive-bred lions are also big business in South Africa, which, until 2018, allowed a legal export of up to 800 lion skeletons annually. Though a lawsuit deferred the annual quota in 2019 and 2020, South Africa is home to an estimated 7,000-14,000 captive lions, which only perpetuates trafficking on a global scale. While many lions are farmed for canned hunts and the parts trade, others make their way onto the market after being discarded by tourist venues in South Africa that offer cub petting and lion walks, among other activities.

While tigers and lions are not bred to be slaughtered in the US, the hypocrisy still hurts conservation efforts. Barylak adds, “When US officials have pressed other nations – including those in which tiger farming continues to grow, reinforcing global demand for parts and products – to restrict such intensive captive breeding operations, they lack credibility and influence due to America’s own unchecked tiger breeding.”

Ligers, tigons and white tigers: what are they and what are the issues around breeding them?

A liger is the hybrid offspring of a male lion and a female tiger, while a tigon is produced by a male tiger and a female lion.

There is no scientific evidence that these hybrids exist in the wild – even if the species encountered each other, behavioural differences between the two would deter them from reproducing. Lions live in prides and coalitions, while tigers are solitary animals.

Crossbreeding makes ligers the largest big cats on Earth, and many suffer from genetic abnormalities. Simply put, big cat hybrids are a man-made species that exist purely for entertainment, and they do not benefit the conservation of wild populations.

White tigers can occur naturally due to a recessive gene, but this is a rare colour mutation among Bengal tigers, rather than a subspecies. Intentional breeding to increase the chances of producing a white tiger often leads to genetic defects – in 2011, the AZA banned member zoos from taking part in the practice.

Image: To ensure offspring carry the mutation, white tigers in captivity are often inbred. © Dinesen Venkatachellam/EyeEm/Getty

Mixed messages around breeding big cats in the US

Complicating matters further is the confusion about accreditation and breeding programmes in the US. While it is not required on a state or federal level, accreditation does offer establishments more legitimacy. However, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the more recently established Zoological Association of America (ZAA) have very different policies surrounding the breeding of and caring for big cats.

AZA’s strictly managed Species Survival Plan (SSP) Program focuses on maintaining genetic diversity at AZA facilities, while the ZAA’s Animal Management Programs (AMPs) support breeding by public and private owners. When it comes to care, AZA enclosures are required to have a pool and natural vegetation, and the recommended size for a single tiger is at least 144m². The minimum size of an enclosure for up to two tigers at ZAA facilities is listed as 33m², and pools are recommended, but not required.

By contrast, accredited sanctuaries, rescues and rehabilitation centres do not support any form of breeding, and both the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries (GFAS) and the American Sanctuary Association (ASA) have strict member policies.

“We do not believe that big cats, who in nature roam huge territories, should be bred for life in a cage,” states Howard Baskin, advisory board chairman of Big Cat Rescue in Florida. Baskin adds that most of the rescued cats at their GFAS-accredited facility come from private owners who are not licensed exhibitors, while others are removed by law enforcement from abusive situations or defunct exhibitors.

In addition to Florida and USDA exhibitor licenses, Big Cat Rescue holds a state rehabilitator license for its work with orphaned and injured native bobcats. It’s worth noting that while Myrtle Beach Safari has a USDA exhibitor license, they are not currently accredited by any zoo, sanctuary or rehabilitation organisation.

Though irresponsible breeding has created an unsustainable captive big cat population in the US, it is also argued that strictly managed breeding benefits education and conservation. The Feline Conservation Foundation (FCF), which supports “responsible” private big-cat ownership, stressed the importance of maintaining a reserve-captive population to avoid species extinction: “Most people will only ever encounter wild animals in their local parks, museums, nearby zoos and science centres,” says a FCF spokesperson. “Education and conservation programmes are charged with helping the public feel more connected to wildlife and preserving the natural world.”

Seeking a real sanctuary

Lifetime refuge for abused and abandoned big cats is provided at legitimate sanctuaries, and many are open to the public. Prior to visiting, it is important to ensure animal welfare is the top priority by looking out for the following criteria.

- The sanctuary is accredited by a reputable organisation, such as the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries (GFAS) or the American Sanctuary Association (ASA).

- Visitors are not permitted to have contact with the animals (feeding, cuddling, petting, posing for photos, for example).

- The facility does not breed, sell or trade animals, and animals do not leave the property except for emergencies or veterinary care.

- Animals are not required to perform, nor are they used for any commercial purpose that is exploitative in nature.

- The animal enclosures are an adequate size and replicate natural habitat, thus providing an enriching environment.

- The sanctuary is a registered nonprofit, and/or has worked with other major animal welfare and wildlife conservation nonprofits.

- Guests are presented with educational messaging about the wildlife trade and protecting wild populations.

Image: Turpentine Creek Wildlife Refuge has more than 100 rescued big cats. © David Pulliam/Kansas City Star/Getty

Predator protection

With habitat loss and poaching leading to the rapid decline of big cats across the globe, extinction in the wild may be unavoidable, and therefore genetic diversity is crucial to the long-term survival of captive species. As it is not feasible to release America’s captive-bred lions and tigers into the wild, it becomes an ethical question as to whether the apex predators should remain in zoos – and potentially in the hands of well-intentioned private owners – in order to prevent them from disappearing forever.

Education and advocacy encourage people to support organisations and practices that protect both captive big cats and wild populations, but creating effective (and enforceable) policy is vital to the survival of these animals. In February 2019, US lawmakers reintroduced the Big Cat Public Safety Act, which would require federal permitting for all big cats and prohibit public contact with cubs.

“This legislation would reduce the risk of tiger parts from the US entering the illegal wildlife trade, remove the strongest incentive for breeding and improve public safety and animal welfare,” states Leigh Henry, director for wildlife policy at WWF. The bill passed the House Natural Resources Committee in late 2019, and a companion measure has been introduced in the US Senate. If signed into law, it would be a victory for big cat conservationists in the US and all over the world.

Main image: Formerly owned by Joe Exotic, Oklahoma’s Wynnewood Exotic Animal Park continues to draw in the crowds. © The Washington Post/Getty