Animals and plants have specialised parts that carry out different functions. They can be used as a form of defence, to enable a species to move through its natural environment, attract a mate or process food. Discover more about fascinating wildlife anatomy.

How does a rattlesnake's rattle work?

No one wants to accidentally step on a rattlesnake. The snake doesn’t like it much either. Happily for all concerned, as it grows, a rattlesnake accumulates small hollow segments of each shed skin at the tip of its tail, which clank together menacingly when shaken. The result is a warning signal as archetypal as a wasp’s black-and-yellow stripes. Increasing the frequency of the rattle adds to the sense of urgency as danger approaches.

Please note that external videos may contain ads.

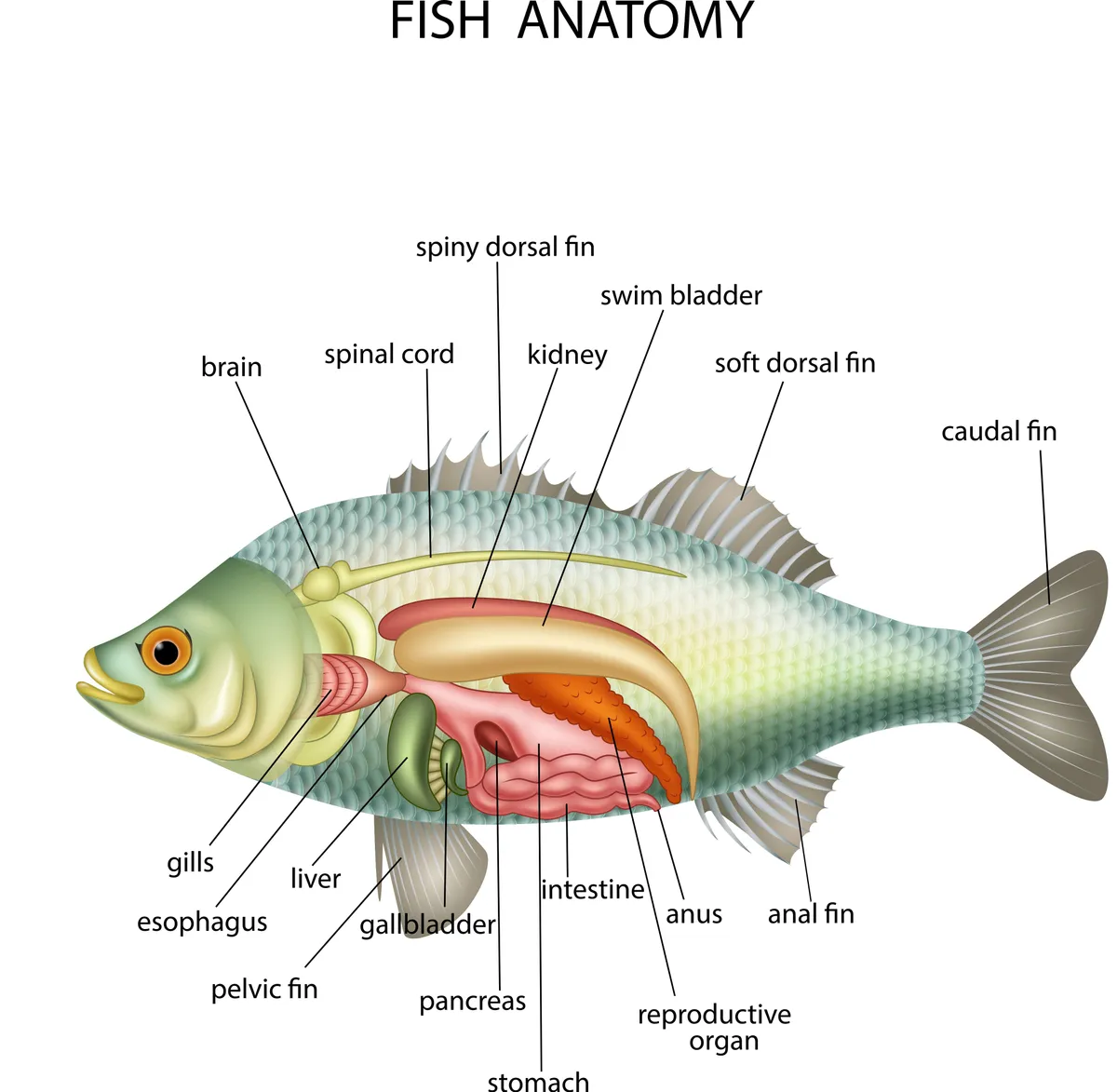

How does a fish's swim bladder function?

Inflatable bags of gas are useful organs whether you live on land (lungs) or in water (buoyancy aids). By inflating or deflating its swim bladder, a fish is able to ascend or dive as required. While lungs are aerated via the mouth, the swim bladder is fed by gases dissolved in the blood. The organs have the same evolutionary origins, though, both developing from simple air sacs used by ancestral fish to gulp air in oxygen-poor waters.

How does a horsefly bite?

The exquisite beauty of horseflies (those iridescent eyes!) belie their utter brutality. No mosquito-like precision here. They simply slice into flesh with a cluster of serrated blades and lap the blood that inevitably flows. They even lack the decency to anaesthetise the incision site - little point when their preferred victims (horses and cattle) are so ill-equipped to swat them. The first horseflies sipped nectar, as the males still do. Females, though, need a blood meal to provision their eggs.

Why do baboons have swollen bottoms?

Scientists haven’t quite got to the bottom of the florid sexual swellings on the hind-quarters of female primates including baboons and chimpanzees. They are at their most spectacular during the fertile phase of the reproductive cycle, when males show the greatest interest in them. However, it’s not clear that females with the fruitiest booties enjoy greater reproductive success. In mandrills, it’s the males that have the rum bums – the more dominant the male, the more louche the tush.

Please note that external videos may contain ads.

What is the purpose of a duck's speculum?

An iridescent jewel nestles amongst the plumage of many ducks. Formed from secondary wing feathers, the speculum is most obvious during flight. Otherwise, it appears as a glinting rhomboid of saturated colour on each flank (purple in mallards, green in teal, white in gadwall, for example). It may play a role in species recognition, but it’s probably no coincidence that it is positioned on the very spot that ducks ritually preen themselves during courtship and competitive displays.

Why do moles have large paws?

If you’re going to spend your life digging tunnels, you’d better have a good shovel. Moles have them in spades - well, two, anyway. Their massive, clawed front paws are built for excavation. Evolution has even transformed one of their wrist bones into an extra “thumb” to help them shift soil in bulk. Moles aren’t the only mammals to have a false thumb fashioned from a wrist bone. A similar structure helps giant pandas grip bamboo.

How does a jellyfish sting?

Jellyfish, corals, anemones – collectively, cnidarians (with a silence c) – aren’t the liveliest of creatures. Yet they perform one of the fastest movements in nature, one that cannot be captured even by high-speed video techniques. Their potent stings are delivered by tiny barbed harpoons, each packed into a single cell full of venom. When triggered, they discharge explosively, like an inverted finger of a rubber glove popping back out under pressure, accelerating faster than a bullet in a gun barrel.

How does a ruminant's stomach work?

The multi-chambered stomachs of cattle, deer and other ruminants are dedicated to releasing the considerable energy contained in the complex sugars that form the structural bulk of plants (indigestible roughage to you and me). The magic happens in the rumen, a fermentation chamber containing an ecosystem of microbes with biochemistry skills lacking in mammals. The resulting cud is regurgitated and chewed again (with a contented far-away look in the eyes) ready for a more conventional digestive process.

Why do roses have thorns?

One might assume that spines, thorns and prickles are different names for the same things. Botanists would disagree, though. They are different structures used for a common purpose: defence against hungry herbivores. Spines - most spectacularly deployed by cacti - are highly modified leaves. Thorns are pointed branches or stems. While a hawthorn’s thorns are true thorns, a rose’s famous thorns are actually prickles – simple outgrowths from the bark, more akin to thick, sturdy hairs.

Why does an amblypygid have jaws?

Are there any jaws more fearsome than the enormous spiked, hinged contraptions wielded by an amblypygid? Strictly speaking, they are not jaws at all, but palps, used by many other arachnid groups as sensory organs. In amblypygids, that job is done by the ludicrously long first pair of walking legs, which silently sweep the surroundings for prey. Woe betide anything that stumbles within touching distance.

Why does a swallowtail caterpillar have an osmeterium?

Unique to members of the swallowtail butterfly family, this other-worldly organ is usually stowed away in a pouch behind the caterpillar’s head, but when danger strikes, it is inflated spectacularly to deter predators with a combination of visual and chemical shock and awe. Predators are repelled by its repugnant smell and its resemblance to a snake’s forked tongue.

What is ram’s horn squid’s shell?

Though it looks like a loosely-coiled snail shell, this is more akin to the cuttlefish 'bones' enjoyed by pet budgies. It’s the internal buoyancy organ of a ram’s horn squid, a deep-sea cephalopod that was observed alive in the wild for the first time only in 2020. The species is largely tropical, but the horns’ buoyancy means they do occasionally turn up on UK beaches.

How do remora fish attach to other animals?

Dorsal fins are used conventionally to prevent a fish rolling to the side while swimming and to help them negotiate tight turns. Remoras, though, have transformed theirs into a structure designed to get other animals to do their swimming for them. The bizarre suction cup on the top of a remora’s head allows them to hitch rides from whales, sharks and other big fish.

What is a starfish’s madreporite?

Look closely at a starfish and you might spot a tiny exquisite imperfection in its otherwise flawless five-fold symmetry. This beauty spot is called a madreporite, a roughly circular chalky plate that sits slightly off centre on a starfish’s upper surface. Dotted with microscopic pores, it works as a seawater intake valve that supplies a system of tubes powering the countless hydraulic tube feet on the animal’s underside.

Why do male mammals have nipples?

Evolution fashions bodies that are exquisitely adapted to their environment. It’s not perfect, though. Why, for instance, do male mammals have nipples when only females need them? Males and females develop along very similar lines using much the same genetic recipe. Characteristics of one sex will, then, be expressed in the other as long as they don’t confer a disadvantage. Male nipples neither help nor hinder.

What are a scorpion’s pectines?

Should you ever find yourself close enough to a scorpion to examine its underside, you won’t fail to spot a pair of large comb-like structures, which, were they to be found on any less fearsome animal, might be likened to an angel’s wings.

Pectines are unique to scorpions and function like insects’ antennae. Sensitive to vibrations and chemical stimuli, they brush the ground as the scorpion moves.

Why is a wrybill’s beak crooked?

Be they long, short, chunky, delicate, pointy, straight or curved, beaks are almost always symmetrical.

The aptly-named wrybill, a plover endemic to New Zealand, is the only species whose beak bends to one side - always to the right.

The function of the asymmetry remains mysterious.

It might allow the bill to be used like a spatula to scrape invertebrate food from the curved undersides of pebbles.

Why do coots have lobate feet?

Webbed toes are great for propulsion in water, but as anyone who has tried walking in flippers knows, they are not built for elegance on land.

A coot’s “lobate” foot is an exquisitely engineered solution to unfettered locomotion in both worlds.

Each toe sports hinged flaps that increase the foot’s surface area for swimming, but can fold back out of the way when not in use.

Main image: Diamondback rattlesnake coiled on a dirt road. © twildlife/iStock/Getty