The population of red handfish remaining in the wild has just dropped from around 100 to 75, as 25 individuals were taken into care at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS).

Concerned about the risk of upcoming marine heatwaves on the critically endangered population, conservationists received special permission from the Australian government to remove some individuals from the wild.

Red handfish are a species of anglerfish. Unlike other fish, they don’t have a swim bladder to control their buoyancy, so they use their large hand-like fins to ‘walk’ along the seafloor. These peculiar creatures are around 8cm long – smaller than a playing card – and pink, red or brown in colour with a grumpy, downturned mouth.

“If you’ve never seen a handfish before, imagine dipping a toad in some brightly coloured paint, telling it a sad story, and forcing it to wear gloves two sizes too big,” says the Handfish Conservation Project on its website.

The species is also incredibly rare, with no more than 100 individuals believed to be left in the wild. The small population is only found in two small areas of rocky reef, southeast of Hobart, Tasmania. This habitat is buffeted by threats including boat traffic, anchoring, urban development, pollution and nutrient runoff as well as non-native species and the impacts of climate change.

Walking along the seabed instead of swimming means these diminutive fish can’t travel far to escape these threats. And they don’t have a larval stage when they’re young so can’t drift through the ocean to spread to new areas.

- Weirdest sea creatures - meet 12 strange sea creatures of the deep

- 10 deadliest sea creatures: Meet the most dangerous animals in the ocean

The location where they are found is now suffering from severe habitat loss caused by the overgrazing of native urchins. Add predicted marine heatwaves to this picture and the outcome could be bleak.

“Habitat degradation means there’s a loss of refuges and microhabitats, creating a disconnected habitat that makes it increasingly difficult for the handfish to adjust to water temperature stress,” says IMAS researcher Dr Jemina Stuart-Smith, who co-leads the university’s red handfish research and conservation program.

"If you’ve never seen a handfish before, imagine dipping a toad in some brightly coloured paint, telling it a sad story, and forcing it to wear gloves two sizes too big." Handfish Conservation Project

“Our temperature data from site showed us that this summer has already well exceeded previous temperature maximums. It is experiencing unprecedented high temperatures, so we can only assume that this additional stressor will impact the already fragile population,” Stuart-Smith says.

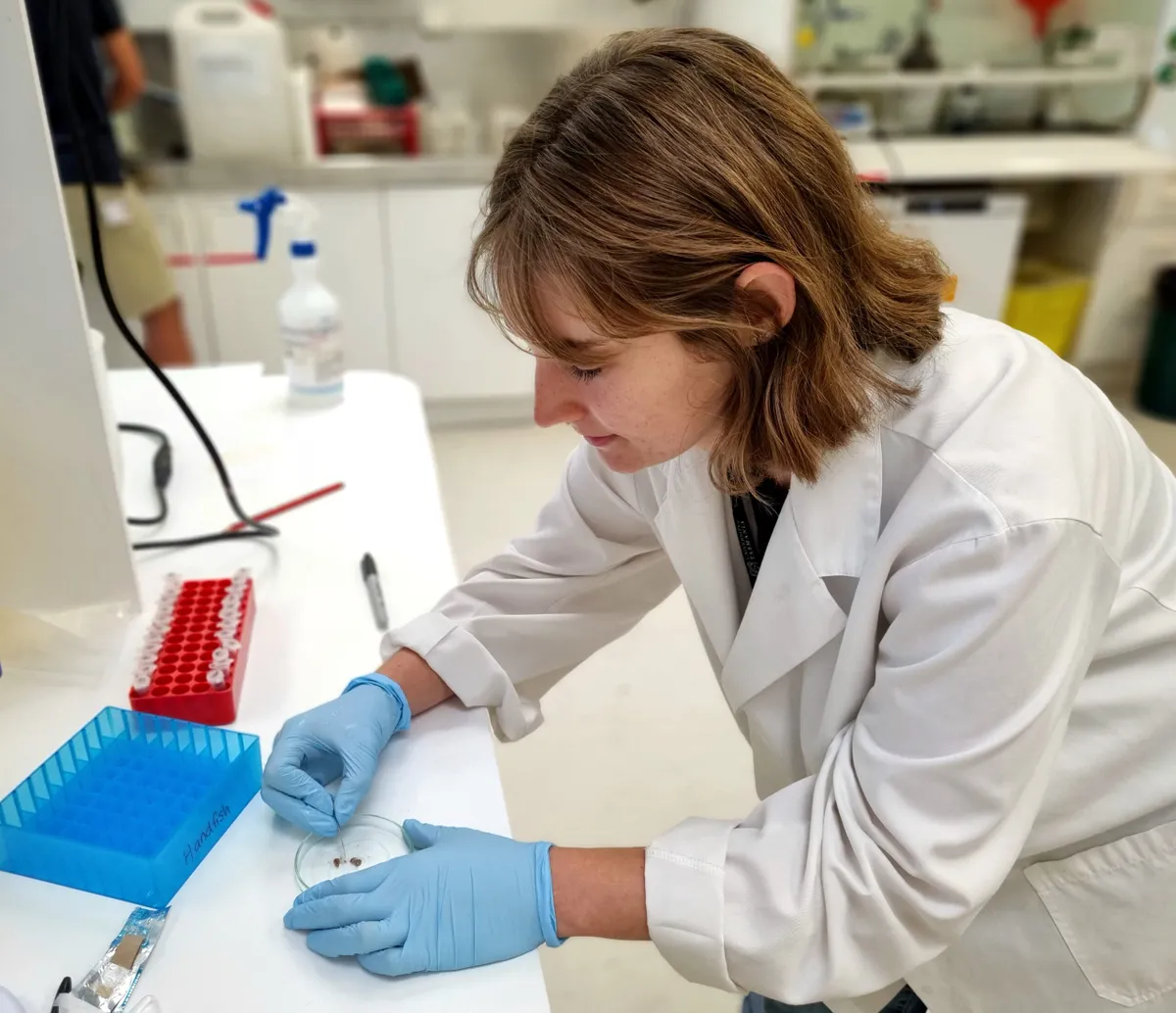

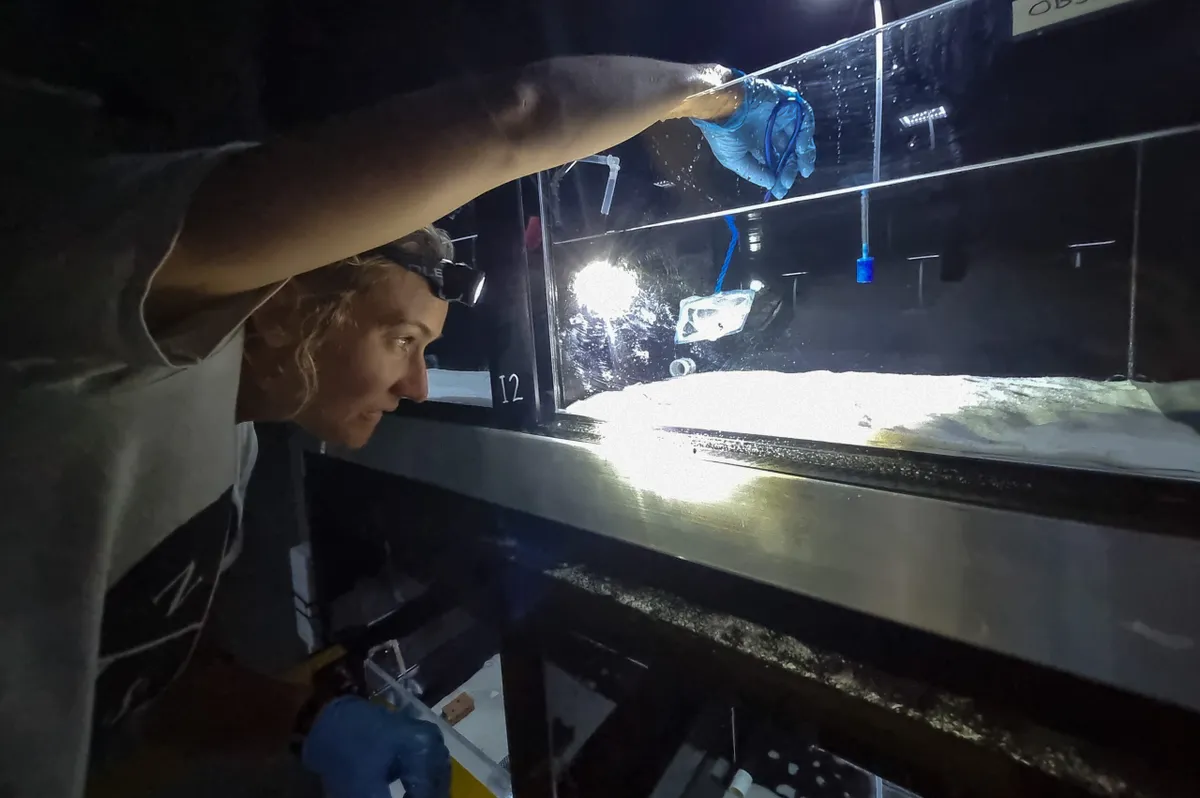

Worried the entire species could be wiped out by increased water temperatures over the summer, experts hosted an emergency workshop to decide what to do. After looking over the data and weighing up the risks, they collected 25 individuals from the wild and have taken them to IMAS Taroona to be looked after.

“This strategy certainly isn’t without risk but the handfish relocation from sea to aquariums was quite seamless and they settled into their new homes very nicely,” says Dr Andrew Trotter, who leads IMAS’ conservation breeding project for red handfish.

“They were feeding very well within a day, and our aim now is to keep them healthy and content until it’s safe to return them,” Trotter says.

“We have highly experienced staff looking after the fish seven days a week, and a 24-hour call-out roster. So, we believe they are quite safe with us – but there is certainly a feeling of heightened responsibility among our team, given how small the wild population is,” Trotter adds.

The team hopes to return the individuals to the wild in the winter if their habitat is suitable.

Until then, they’re focused on restoring and managing their habitat while they keep the 25 individuals safe in the aquarium, says Trotter: “We don’t want to keep them any longer than necessary – they’re wild animals and belong in the sea.”