For those of us of a certain age, egg collecting was a key ritual in becoming a naturalist. It usually meant pinching the odd blackbird or dunnock egg from your garden or a local hedgerow. Today, of course, taking eggs is illegal under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 except for some species under licence in specific circumstances) – and quite rightly.

As a result, identifying birds' eggs is something we've become less good at: when we spot one, the species it belonged to is often a mystery. But you don't need to break the law to be an egg-detective – the signs are all around us. What are those fragments of speckled eggs on the garden path? Who laid that bright blue egg dumped on the lawn?

Remember, eggshells don’t just fall out of a nest. Predators such as foxes or magpies may carry them away, as do parent birds, often to help conceal the location of vulnerable babies.

Examine every egg for clues. In an egg that hatched naturally, a hole will tend to open outwards as the baby emerged; in predated eggs, holes are punched inwards.

And once you've found an egg, come back here if you need a hand with the identification.

Learn how to identify birds' eggs with our expert guide, including which species it came from and where you are most likely to see birds' eggs. We have illustrated the dozen eggs you're most likely to find in your garden or local park or on a country walk. Note the markings may vary a great deal; the sizes quoted are length x breadth.

How to identify birds eggs

Starling eggs (Sturnus vulgaris)

Starling eggs are smooth and fairly glossy, 30 x 21mm in size. They are pale blue eggs with no markings. They are sometimes found whole, with unhatched eggs, largely due to infertility.

Starlings nest in colonies, with all individuals feeding in a communal foraging ground. Male starlings construct the first part of the nest and sing on a perch nearby in order to attract a mate. When a female finds a satisfactory male, she will finish the nest by lining it with insulating material.

Clutches of 4–6 eggs occur in the nest in April, with chicks hatching twelve days later, and fledging after three weeks. The majority of starling chicks make it to adulthood.

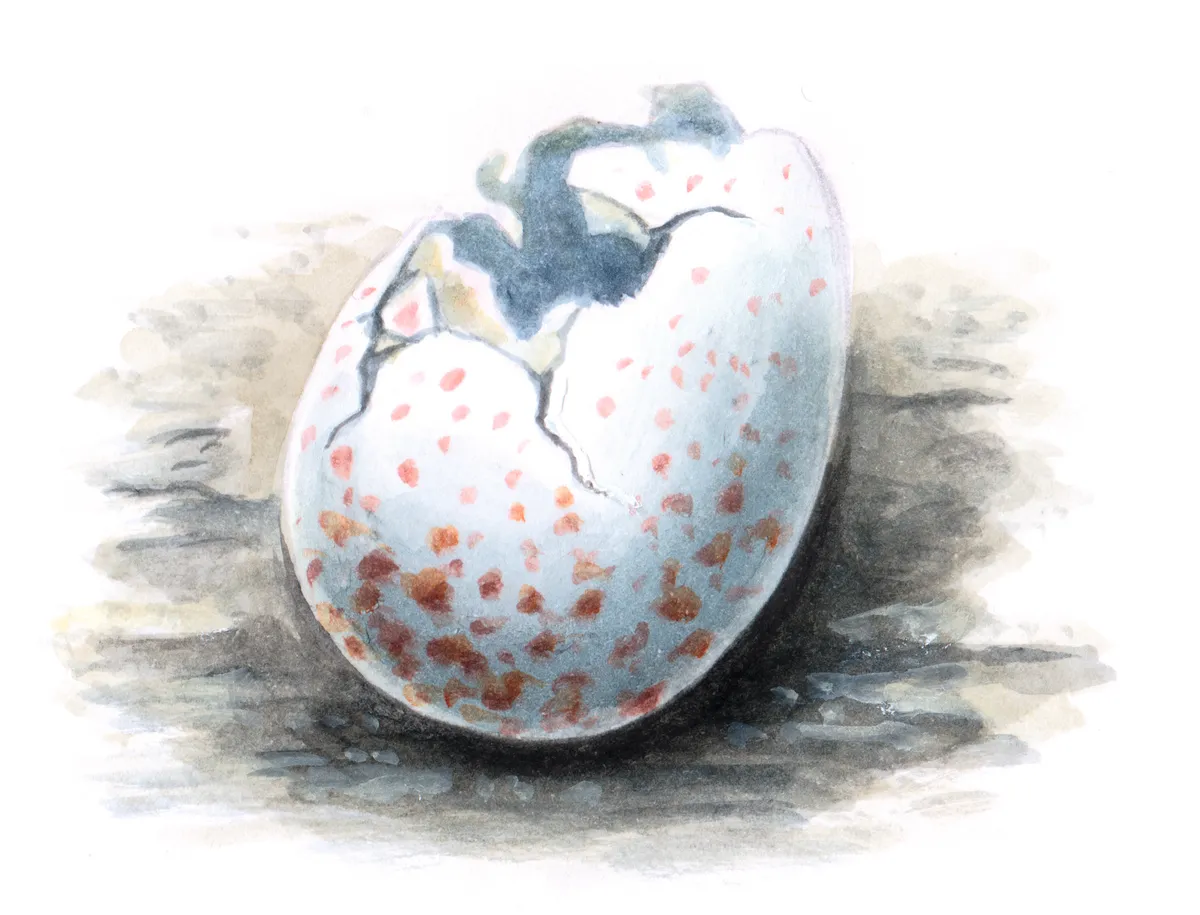

Song thrush eggs (Turdus philomelos)

Song thrush eggs are smooth and glossy,31 x 22mm large. They are very pale blue eggs with a few large dark speckles, mostly at the wider end.

The nests are usually constructed out of mud, with no grass lining. If coming across eggs in the nest, this will be an easy distinguishing factor of the song thrush versus other birds with similar eggs.

Clutches of 4–6 eggs are laid in early spring and, after they fledge, the chicks are fed by the parents until they reach maturity.

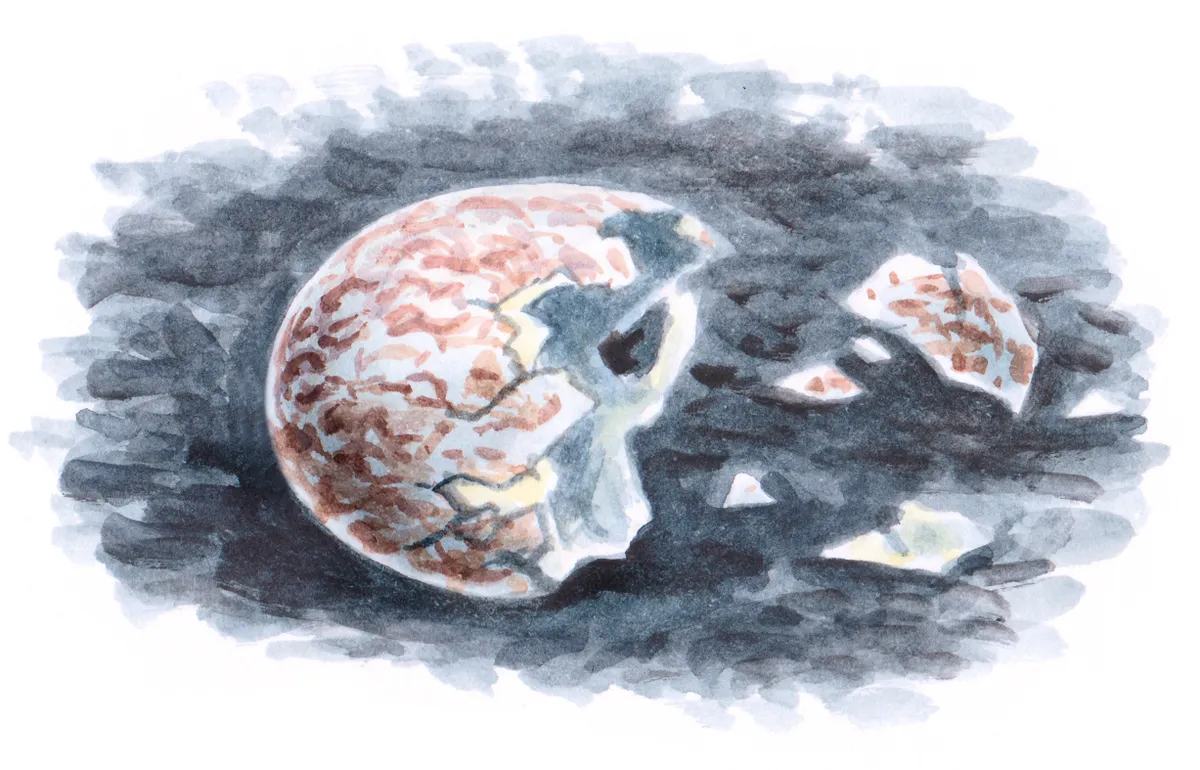

Blackbird eggs (Turdus merula)

Blackbird eggs are smooth and glossy, 29 x 22mm in size. They’re green-blue or completely blue eggs with heavy red-brown freckles that can make them seem brown overall.

The nest is similar to a song thrush, with a backbone of twigs, a plaster of mud and a lining of fine grass. Two to four broods can take place each year depending on weather, and the nest can be reused to accommodate them all. The birds take just two weeks to fledge, but can survive from as young as nine days old if they are forced to fledge early. The young blackbirds hide in nearby cover until they are able to fly.

Males care for the chicks as they flutter and explore food items, while females stock up on energy to lay another brood.

Robin eggs Erithacus rubecula)

20 x 15.5mm, robin eggs are smooth but with a matte finish. They’re white eggs with variable fine brown freckles, and the whole egg may seem buff.

Robins pair for the breeding season but are independent the rest of the year – they usually begin courting in late winter or early spring. Males feed the female as she sits in the nest, supplying her with about one-third of her food.

Robins abandon nests easily if they fear they have been discovered, as they nest on the ground. They have been known to nest in curious places, like inside boots, kettles, or coat pockets. Shells can frequently be found on the ground as the female removes them immediately after chicks have hatched, though she sometimes eats part of them for their calcium content.

After two weeks the chicks fledge, but they are still cared for by their parents for a further three weeks as they totter around on the ground. Three or four broods can be laid a year, with nestlings found into the summer months. Robins have very strong nurturing instincts and are sometimes found to feed the young of other species.

Dunnock eggs (Prunella modularis)

Dunnock eggs are smooth and glossy, about 20 x 15mm in size. They are bright-blue eggs that are unmarked; smaller than superficially similar starling eggs.

The eggs may be unassuming, but the breeding habits of dunnocks are promiscuous. Males and females strive to give themselves the best chance that their genes are passed on to the next generation. For males, this means mating, and making sure they are the only male mating with a given female. For females, this sometimes means mating with more than one male, so that they will both help raise her chicks and give them a higher chance of survival.

Sometimes males can be seen pecking a female’s cloaca – the opening through which waste products exit and reproductive activity takes place – before mating with her. In doing this, they hope to cause her to expel the sperm of any other males she may have mated with before them.

Dunnock eggs are laid in a nest of grass, leaves and roots. They are frequently targeted by cuckoos, which remove one dunnock egg and replace it with the much larger cuckoo’s egg.

House martin eggs (Delichon urbica)

19.5 x 13.5mm in size, house martin eggs are smooth and slightly glossy. They are plain white eggs and are sometimes found under eaves near predated nests.

They are summer nesters, being completely depending on flying insects for their diet and to feed their brood. The birds have become naturalised to residential areas, nesting in colonies, commonly under eves in spherical nests made of pellets of mud mixed with grass, lined with insulating material like feathers.

The eggs are incubated for two weeks by both parents, and the chicks take three weeks to leave the nest, though they remain in the colony for several more weeks. In food shortages, the hatchlings can go in to a state of torpor, where some of their metabolic processes are shut off to enable them to survive. First hatchlings often help the parents to feed successive broods.

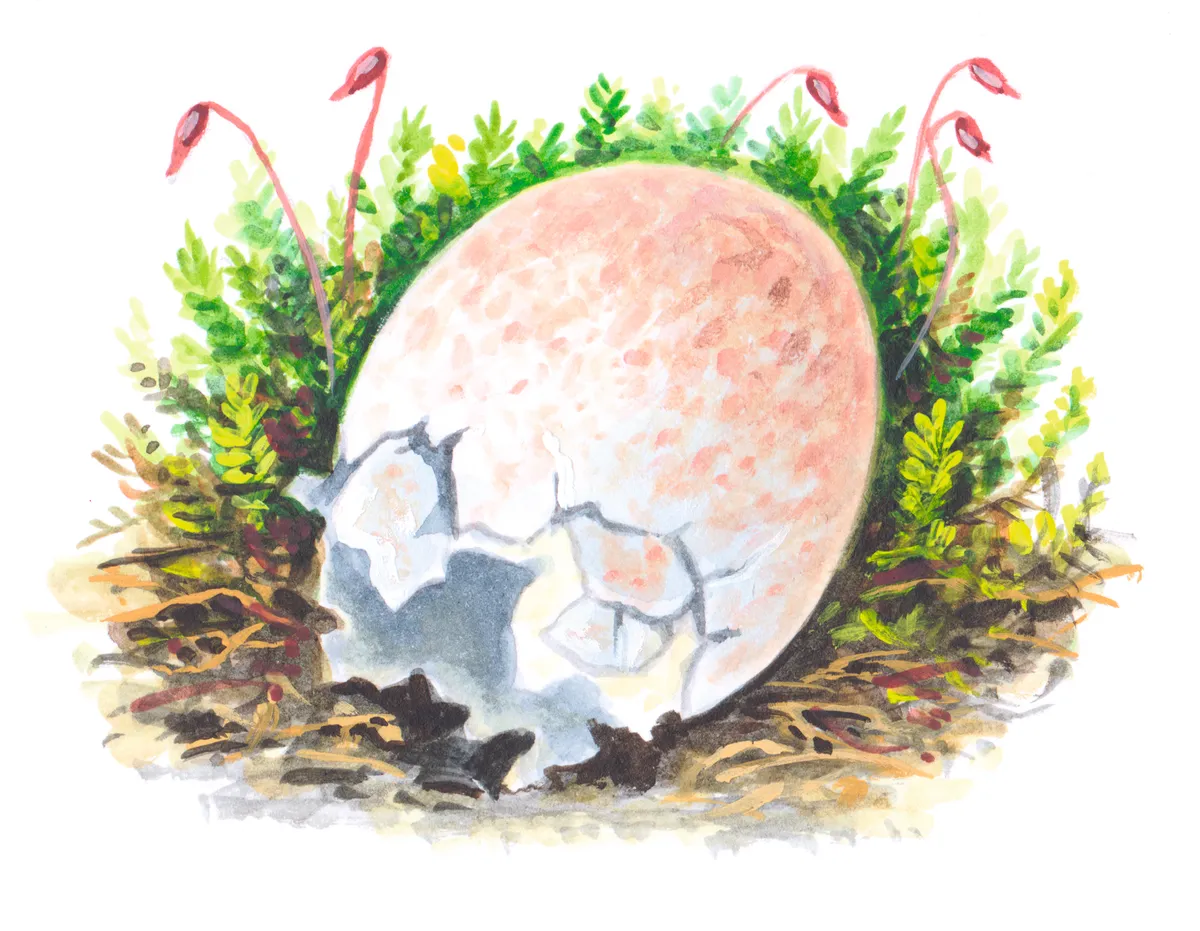

Pheasant eggs (Phasianus colchicus)

At 46 x 36mm, pheasant eggs are the size of a small hen’s egg. They’re usually olive-brown eggs, but can be brownish or have blueish tones.

Nests are constructed on the ground, by digging out a pit concealed among tall grass. Males are fiercely territorial, commanding foraging grounds and a harem of females which he mates with. Pheasant chicks are similar to chickens, hatching already covered with feathers and able to leave the nest. They follow the female around and forage for food with her. They are omnivorous birds, feeding on seeds, berries and grass, as well as small invertebrates.

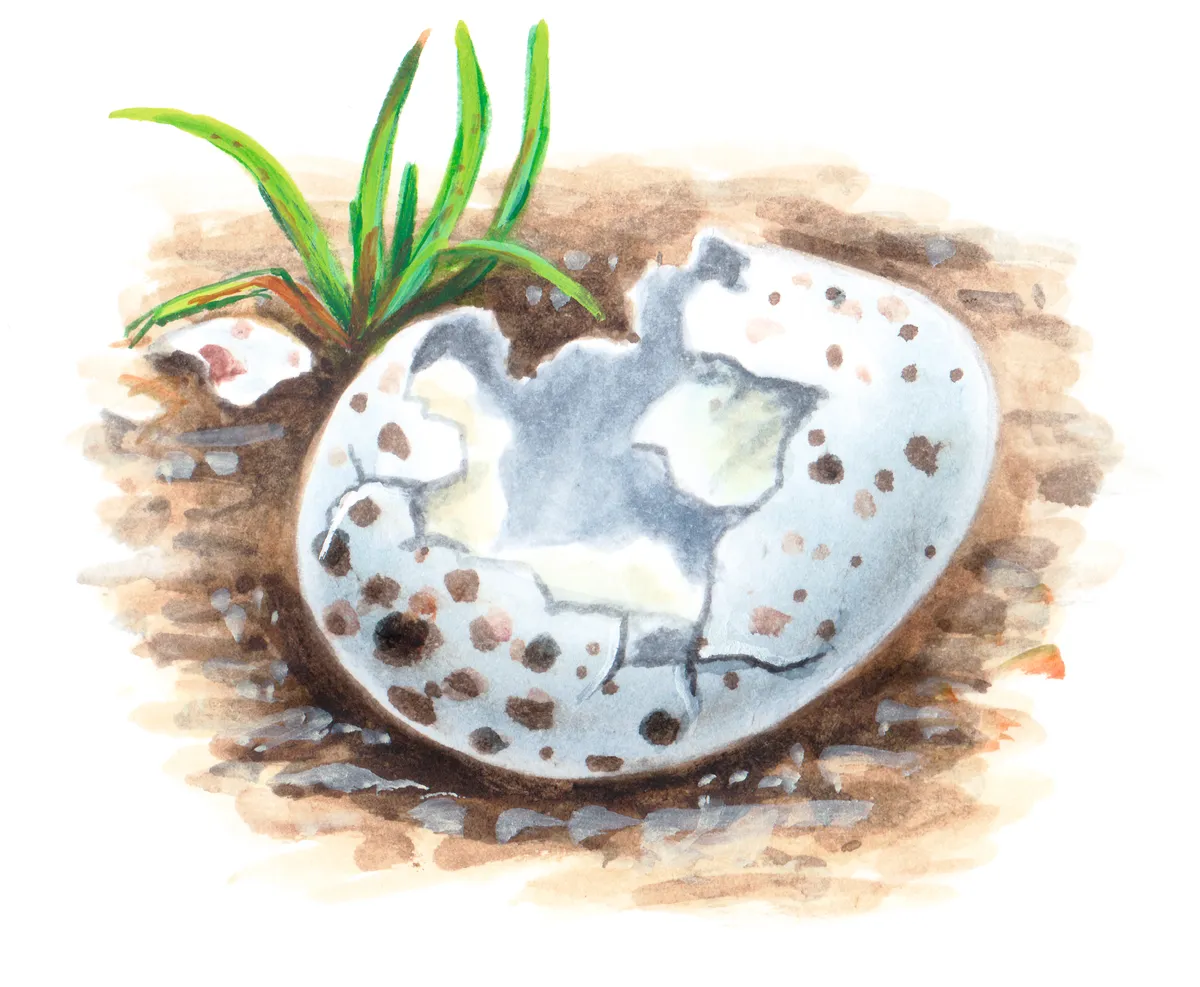

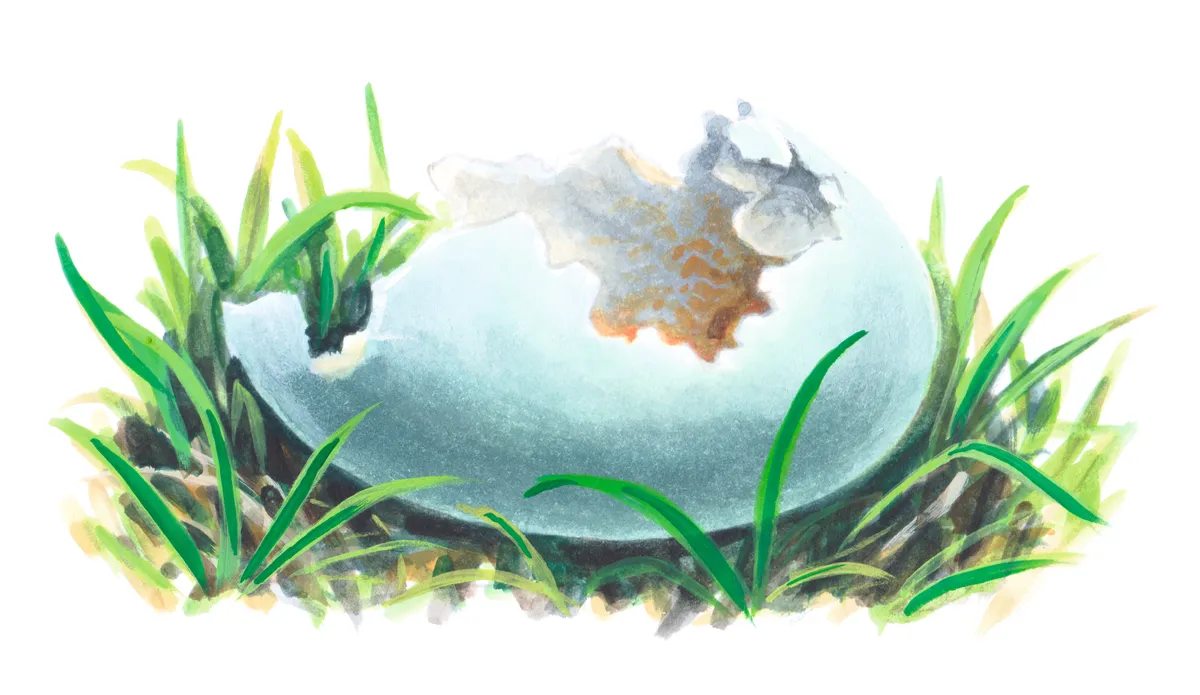

Mallard eggs (Anas platyrhynchos)

Mallard duck eggs are 57 x 41mm large and smooth with a matte or ‘eggshell’, rather than a glossy, feel. They’re typically pale blue-green.

Nests are nothing more than shallow pits in the ground. Surrounded by tall grass, and while sitting in the nest the female may line it with vegetation and twigs that she can pluck from around her, as well as her own feathers. She also pulls grass over the top of the nest to conceal it. They are located near water and the location is chosen by both parents during flights at dusk.

As it takes a lot of energy for females to lay the eggs, she depends to a high degree on her mate for protection and food. Males remain potent for an extended period in case the first brood fails and females need to mate again. During this time, they may forcibly mate with females.

Eggs are incubated for about a month, but hatchlings can leave the nest in about half a day. They will follow their mother to water and begin feeding immediately.

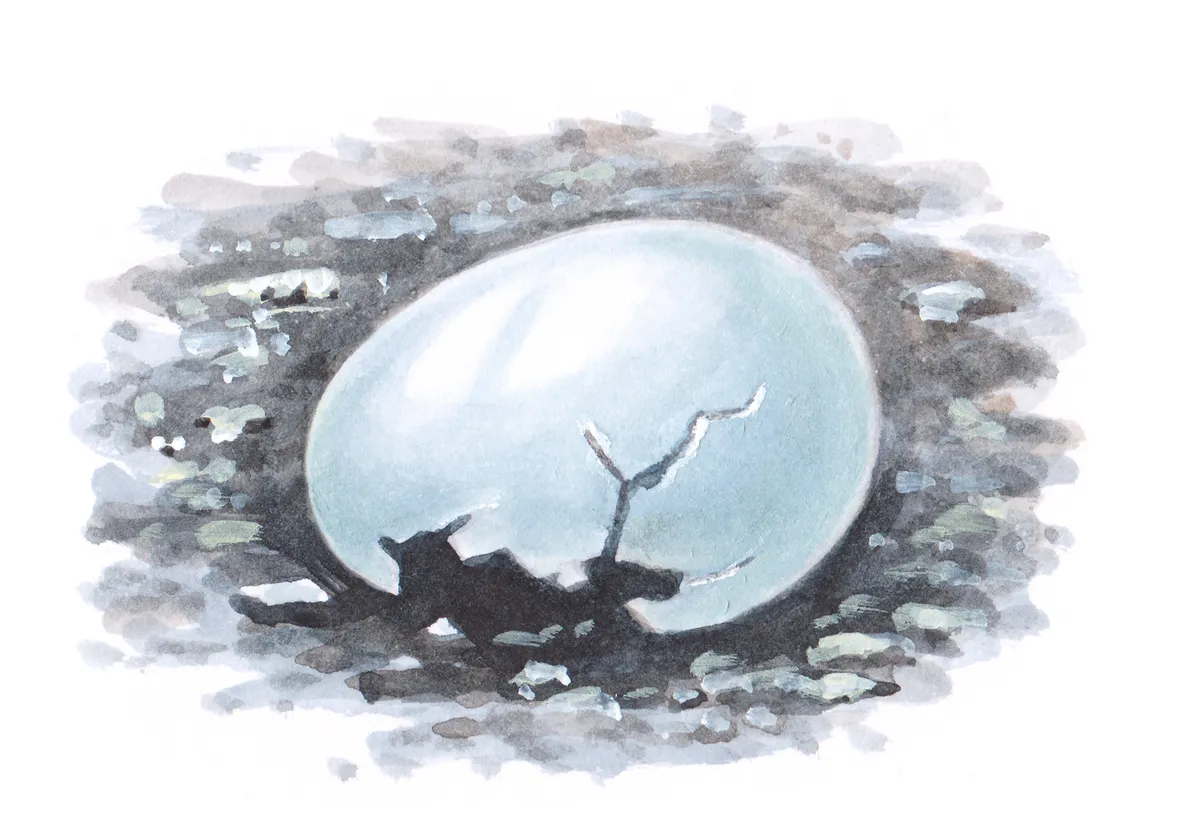

Canada goose eggs (Branta canadensis)

86 x 58mm, Canada goose eggs are one of the largest eggs you’re likely to encounter. They’re white or cream, not glossy, and have no markings.

Introduced to the UK about 300 years ago, they have since spread to a large range and can be inconvenient in some areas due to their habit of congregating in large numbers. These congregations are usually made up of related birds, and pairs mate for life. They nest on open ground, usually in slightly elevated areas that give them a good vantage point for approaching predators. The nests are depressions in the ground, lined with the bird’s body feathers, and made out of grasses, mosses and leaves.

The chicks emerge well-formed, leaving the nest after about two days, during which time they are sustained on reserves from their yolk sac. After two days, the mother leads the chicks to water where they begin feeding. Their diet consists of grain, grass, and underwater plant matter.

Great tit eggs (Parus major)

17.5 x 13.5mm in size, great tit eggs are slightly glossy. They are white in colour, with variable amounts of reddish or purplish speckling.

Adults feed on sunflower hearts and other seeds, but young require a diet of grubs and caterpillars. Parents must establish breeding territories early on in the year and assert their dominion over them. 7–9 eggs are laid during spring and summer, and young birds fledge about three weeks after hatching.

Nests are made of a structure of twigs and roots, lined with softer hair for insulation. The nest is high off the ground, usually in a crevice of a tree.

House sparrow eggs (Passer domesticus)

House sparrow eggs are 22.5 x 15.5mm and slightly glossy. The eggs are white with variable, often heavy, speckling in browns and blue-greys.

The chicks only take about two weeks to fledge and their parents continue to care for them for two weeks further, as they cannot feed themselves during the first week out of the nest. The male sparrow is usually in charge of these chicks while the female prepares to lay the next clutch of eggs – throughout their April to August nesting season, sparrows may raise four clutches.

House sparrows nest in colonies, just a few inches from each other. The nest is generally messy and can include twigs and wool. They survive on a diet of grain and insects.

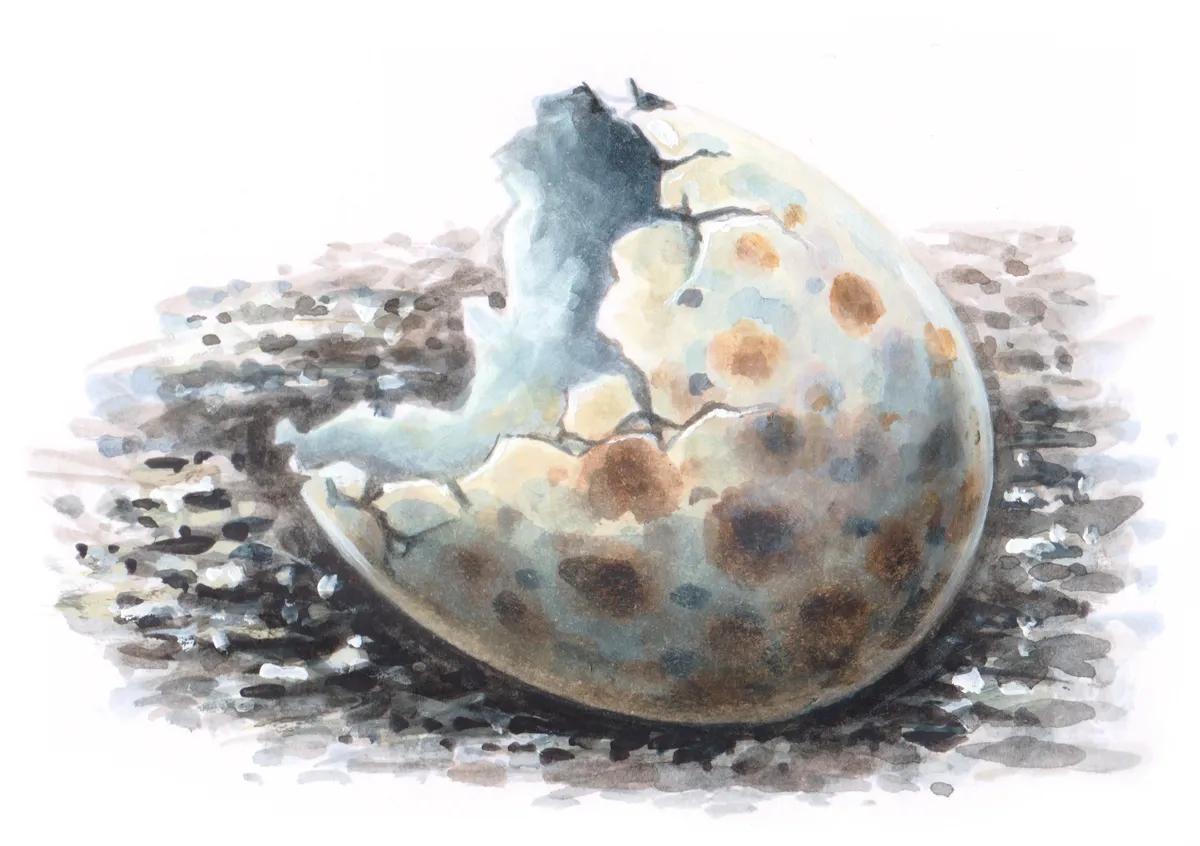

Herring gull eggs (Larus argentatus)

Herring gull eggs aren’t glossy; their surface is minutely sculptured. The 70 x 48mm eggs are brownish or blue-green with variable flecking.

They generally nest in sea cliffs or sand dunes, but some gulls nest far inshore, in urban areas. Here they may be safer and, as indiscriminate feeders, they benefit from the rubbish tips found near cities. However, chicks raised on human garbage dumps instead of fish generally show poorer survival rates due to the impoverished diet.

Near the sea, gull pairs make well-constructed nests of twigs and grasses, usually near a wind-break or inside a crevice. The chicks are fed by both parents and move to an area of nearby vegetation after a few days. They fledge after five or six weeks and parents continue to care for them after this.

Gulls reach sexual maturity at four years old and can live for 20 years. They have been identified as at risk despite their seeming urban abundance. Their population was affected greatly by human hunting in the 1880s, and general threats to their habitats and traditional food source of fish may be contributing to decline today.

Main image: Great tit nest with a clutch of eggs, Norfolk UK. © David Tipling/Education Images/Universal Images Group/Getty