What’s valuable about tigers is not their meat, but their bones and pelts. Bones are used to make products such as tiger bone wine, even though this has been technically illegal in China since 1993.

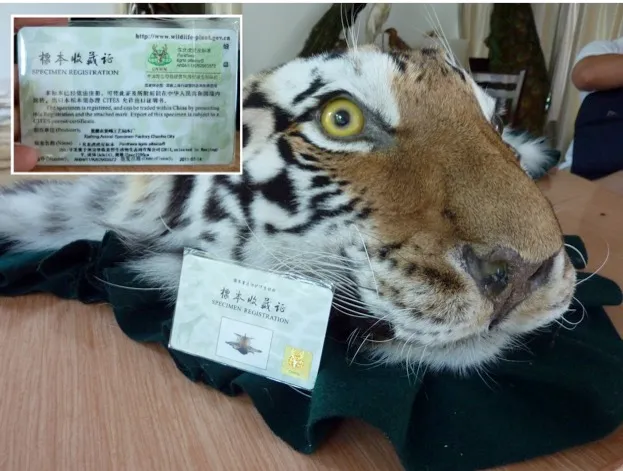

Pelts are sold as luxury rugs – this is legal within China, as long as they are accompanied by official permits.

Aside from the welfare considerations of keeping tigers in farms, many conservationists say that it impacts the survival of the species in the wild.

On the one hand, there is an argument that having a legal trade in captive-bred tiger parts reduces the pressure to poach wild tigers.

But according to the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), this legal trade in tiger skins is perpetuating its desirability and acceptability and stimulating demand.

“The legal trade has had no impact on criminal networks and has continued to drive poaching of wild tigers – and indeed leopards and snow leopards as substitutes – for the same consumer markets,” the EIA says.

Now, the EIA is concerned by amendments to China’s Wildlife Protection Law (WPL), which, it says, devolve authority from central to provincial government for regulating both the breeding of tigers and the utilisation of products – such as bones – derived from them

There is already a problem, the EIA says, with monitoring domestic trade in tiger parts, and the new system risks making it even harder.

“[We are] extremely concerned that the revised law risks further entrenching the culture of commodification of tigers at a time when the world’s remaining wild tigers desperately need China to work towards ending demand,” it adds.

It’s not all doom and gloom for tigers – recent efforts to crack down on poaching in India and Nepal have seen populations rise, and the governments of neither country permit tiger farming.

But tigers were also once found over much of China, and there is little chance of them reclaiming their former range there while trade continues, says the EIA.

Main image: Tigers are kept in farms to be killed for their pelts and bones. © EIA