Photographer Brydon Thomason's intimate portrait of the wildlife found in remote, rugged Shetland:

Coastal clamber

Shetland is home to the highest density of Eurasian otters in the British Isles. These animals find much of their prey on the seabed, moving with ease among fronds of kelp suspended in the water. During low spring tides, however, the ‘fallen forest’ is more akin to an obstacle course, and foraging is much more challenging.

Back from the sea

Puffins usually start to arrive back on Shetland’s clifftops during the first week of April, having spent more than seven months weathering the wildest storms in the open ocean. Once safely back on land, the birds rekindle their pair-bonds and reclaim their breeding burrows.

Storm warning

January and February bring gale-force winds to Shetland. Waves, powered by the North Atlantic, reach more than 12m in height and mercilessly pound the coast.

Pretty in purple

Confined to Northmavine, the wild and rugged north-west corner of Mainland Shetland, purple saxifrage is an early spring speciality and a welcome splash of colour. “It reminds us of the botanical beauty in store,” says Brydon.

Hungry mouths

Having spent the winter in milder climes, skylarks start to arrive during February. Here, four hungry hatchlings beg for food, their patterned tongues and vivid gapes ensuring their parents know exactly where to place the food.

Flight fantastic

Prolific and successful seabirds, gannets have been breeding on Shetland since 1914, famously on the stacks of Hermaness. They are masters of the air, soaring in synchrony over their colonies.

Miniature magic

A wood mouse, known locally as the ‘hill moose’, leaps through long grass. Its nickname is an apt one, as the species tends to favour hills, moorland and pastureland. It is one of only three rodents found on Shetland, along with the house mouse and brown rat.

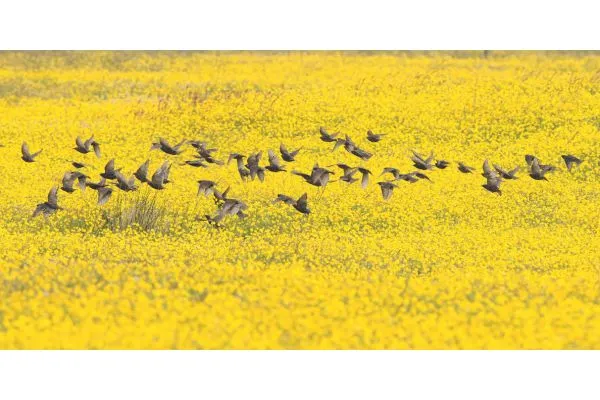

Flock together

Shetland has its own subspecies of common starling, which sports a slightly longer bill. Here, these sociable birds flock over a field of dazzling buttercups.

Seeking sandiloo

Shetland hosts a healthy breeding population of ringed plovers, handsome birds that occur in a variety of habitats from shingle beaches to the highest hills. “The ringed plover has one of our nicest-sounding dialect names – ‘sandiloo’,” says Brydon.

Autumn arrivals

The long-eared owl is one of Shetland’s two commonly recorded owls (the other is the short-eared). In flight, its usually prominent ear tufts are held flat. In autumn and winter, more individuals arrive from elsewhere in Europe, often returning to the same roost-sites in gardens and plantations.

Lady in waiting

Basking in the sunshine, the painted lady is one of just five species of butterfly regularly sighted on Shetland. Studies have recently revealed that those that emerge in northern Europe in late summer migrate at an average height of more than 500m back to the regions of tropical Africa that their grandparents (or great-grandparents) originated from earlier in the year.

Magic merlin

The merlin is a rare bird of prey in the UK. Even in Shetland, which is considered the species’ stronghold, the breeding population numbers little more than 30 pairs. As with all falcons, males are smaller than the females and do most of the hunting. Successful broods of four or five are not uncommon, with the young fledging at 30 days.

Wax and wane

The waxwing is an irruptive migrant, meaning it moves in large numbers according to food availability. These flamboyant birds are usually scarce visitors to Shetland, but in years when fruiting trees in Scandinavia and Russia yield poor crops, they can arrive in decent numbers.

Going the distance

Arctic terns spend the summer months of May to September on Shetland. These hardy birds undertake the longest avian migration in the world, travelling from pole to pole.

Daylight hunter

Separated by more than 160km of ocean, Shetland’s otters have become genetically isolated from those elsewhere in the UK. Unlike those on the mainland, they are primarily diurnal hunters, due to the fact that the majority of their prey is nocturnal, and thus easier to catch while resting on the seabed during daylight hours. Otters locate prey through their finely tuned whiskers, which they use to sense the movement of fish.

Ocean giants

As in other British and Irish waters, sightings of humpback whales have increased around Shetland in the past decade. The upturn is likely due to changes in prey distribution and altered migration routes as a result of global warming. The whales can turn up at any time of year, but most frequently in winter. Some individuals stay for weeks, offering world-class whale-watching opportunities. “To enjoy these giants in Shetland is wonderful,” says Brydon, “but it may not be a positive thing: time, and research, will tell.”

Eyes on the skies

With its northerly latitude, Shetland is well positioned for the phenomenon of the Aurora Borealis – one of the most spectacular and iconic natural spectacles on Earth.

About the photographer

Brydon Thomason is a naturalist, photographer and tour leader, and was born and bred on Shetland. These images are from his new book: Wild Shetland Through the Seasons (The Shetland Times Ltd, £36.99).

Looking for more wildlife inspiration?

Check out our guides to recent photography competitions, including Ocean Art Underwater Photo Contest 2023 and the Environmental Photographer of the Year 2023 winners.