It may be nearing the end of summer, but many animals and plants are springing into action.

Willow warblers (Phylloscopus trochilus)

The great wave of migratory warblers and chats leaving our shores in September and October is larger than in spring, since it is swelled by this year’s young birds. Among them are several million willow warblers, en-route to the forests and wooded savannahs of sub-Saharan Africa.

Juvenile willow warblers are really quite eye-catching: much yellower than their parents, including in the stripe over the eye. Any patch of scrub, hedgerow or woodland near the coast is likely to have a few this month. They are restless birds, flitting through vegetation to feed up for the journey ahead.

Chiffchaffs are also on migration, though often leave Britain a few weeks later, and it may not be possible to tell them apart. However, they tend to have darker bills and legs than willow warblers.

European wasp (Vespula germanica)

Long ago, the tube-like egg-laying organ of female wasps evolved into a sting. A hundred million years later, this remarkable innovation ruins many a September picnic. But why do these insects suddenly become hell-bent on interrupting al fresco meals and venturing inside our homes at this time of year? See it from their perspective and everything starts to make sense.

Queen German, or European, wasps – the main species of social wasp in the British Isles – have stopped laying eggs. And with no new larvae, the end is nigh for the squadrons of female workers, which by this stage in a successful colony’s life-cycle may number several thousand. They’re doomed because, unlike the carnivorous, protein-hungry grubs, adult wasps sip sugars. Earlier, these were provided by the grubs in the nest, as a sweet fluid secreted in exchange for being given meat. Now the worker wasps must fend for themselves, so in their dying days they search gardens, parks and the countryside for nectar and fruit. As these supplies dwindle, they target our food instead.

Common tern (Sterna hirundo)

Seabirds are on the move in September, with many heading to waters off Portugal or western coasts of Africa. Common terns go as far as the Cape of Good Hope, fishing the Benguela Current and mingling with southern species such as albatrosses. Uniquely among the five tern species found in Britain and Ireland, they breed at gravel pits, lakes and reservoirs (even in some cities), as well as on coastal shingle. On migration, too, they can be encountered at waterbodies inland. So keep your eyes and ears open this month for any streamlined ‘gulls’ with buoyant, superbly graceful flight and shrill cries.

Common terns are famously hard to separate from Arctic terns, also migrating this month. Both species have the nickname ‘sea-swallow’ due to their long tails but while adult Arctics will still be in summer plumage, many adult commons have already moulted, so have a whitish forehead and dark bill. Juveniles of both species look similar.

Hops (Humulus lupulus)

With the explosion of interest in craft beer, frequently brewed using trendy varieties of hops from New Zealand or the north-west USA, we have rather forgotten the long tradition of growing hops in Britain. The plant has been cultivated here since the late medieval period, after flavouring beer with hops took off in what is now Holland and Belgium. Today, hops grows wild in many areas, though most commonly in southern England. It is a vine, usually seen rambling over other plants in hedgerows and thickets.

Hops plants are male or female. In summer, the former produce inconspicuous white flowers, which are wind-pollinated and not hugely important for insects.

The flowers on the female plants, best looked for in August and September, are rather unusual – a little like small green pine cones.

Common harvestman (Phalangium opilio)

Numbers of many arachnids peak in late summer and early autumn, which is how harvestmen got their name. Eight-legged but not spiders, these wonderful creatures have long, spindly limbs holding up a body that always seems much too small. It is a single pea-shaped structure, whereas spiders have two body sections. Harvestmen lack venom and eat just about anything.

Wood mouse (Apodemus sylvaticus)

Come September, hazelnuts are ripening fast and wood mice are hoarding as much of this bounty as they can. Any nuts they polish off now are easy to identify. Look for empty shells with a neat circular hole chiselled in one end (the work of the lower incisors) and a few longer scrapes around the outside (where the upper incisors gripped the nut).

Elder (Sambucus nigra)

Think back to May and June, when elder trees were smothered in cream-coloured, deliciously sweet-scented flowers. The blossom buzzed with all manner of insects, especially hoverflies and pollen beetles – and flavoured many a refreshing cordial. Three months down the line, flowerheads pollinated in spring have become luscious clusters of shiny berries. These often appear black, but are actually dark purple.

Don’t be tempted to try a raw elderberry: they’re at best unpalatable, at worst toxic. However, to a bird, they are simply irresistible! Starlings, woodpigeons, blackbirds, thrushes, robins, tits and warblers all tuck in. Researchers have discovered that more species of bird feast on elderberries than any other native British fruit. Given elder is a compact tree, the double whammy of blossom and fruit makes it a brilliant addition to the garden.

Common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus)

By September, rough grass can be heaving with small mammals, moving unseen through the thatch of golden stalks at ground level. Some years in Britain, field voles are thought to outnumber humans. This suits kestrels, whose fortunes are tied up with those of the chubby, short-tailed rodents. Voles mean kestrels, and where they are plentiful, the dashing falcons occupy smaller territories.

The birds may stay on familiar home turf all year, though others – in particular, juveniles fledged over the summer – move to fresh hunting grounds in autumn, often by the coast.

Kestrels have an unrivalled ability to hang in mid-air, tilting their long tail from side to side to keep their head perfectly still as they hover over a few square inches of grass. With great efficiency, they maintain a laser-like focus on their prey, before plunging for the kill. But their populations are also in freefall, due to a perfect storm of threats, including habitat loss.

Now a new study has suggested a link between declining kestrel numbers and rodenticides. If only landowners avoided using rat poison and allowed their marginal pieces of land to grow a little wilder, the once-ubiquitous ‘windhover’ might yet recover.

More related content:

- How to identify bird feathers

- Cuckoo guide: why they call ‘cuckoo’, how they trick other birds, and where they go in winter

- 11 animal species that have come back from the brink of extinction

Woodcock feather. © Mike Langman

Canary-shouldered thorn moth (Ennomos alniaria)

Moth names are so poetic, and early autumn is the season for sallows, carpets, umbers and thorns. Among the latter group, the canary-shouldered thorn stands out as a dandy, with astonishingly bright sunflower-yellow head and thorax fuzz. This ‘fur’ provides a striking contrast to its wings – and to other moths active in September, most of which mimic the more muted palette of autumn leaves.

Canary-shouldered thorn larvae spend spring and summer feeding on a variety of deciduous trees; the species has a wide distribution throughout Britain, including in gardens.

Little stint (Calidris minuta)

This dinky wader is as small as they come – indeed, the second part of its scientific name is minuta. But although the little stint weighs not much more than a chaffinch, this hyperactive bird packs on board enough fat to power a migration in late summer from the Arctic tundra to the shores of western Europe from where, after refuelling on mud-dwelling invertebrates, it pushes on to Africa for the winter.

In September, many of the stints seen in the British Isles are juveniles, most of the adults having passed through a few weeks earlier.

Speckled bush-cricket (Leptophyes punctatissima)

A still September evening is an ideal time to enjoy the chirping of a bush-cricket, produced by rubbing its wings together. Follow the sound to its source by searching hedges or bushes for a grasshopper-like insect with hugely long antennae. The song, called stridulation, is unique to each species (of which Britain has several), and speeds up in warmer air.

In his column for BBC Wildlife Magazine, Richard Mabey once revealed that his late friend Roger Deakin had the romantic idea of creating a musical instrument by keeping several crickets at different temperatures!

European goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis)

Like many songbirds, finches gravitate to flocks after breeding. Aptly named charms of goldfinches can easily grow to be several dozen strong, especially where there are thistles, scabious or knapweed, whose small seeds these fine-billed finches adore.

If disturbed, they rise in a flurry and circle a few times, filling the air with tinkling calls before settling. The birds are busy moulting now. Juveniles are acquiring their first-winter plumage, so often look scruffy around the head and shoulders, as their white, black and red adult feathers begin to appear.

The scientific name of the European goldfinch, Cardeulis cardeulis, is an example of a tautonym, where the genus and specific name are the same.

Silk button gall (Neuroterus numismalis)

Galls are weird and wonderful plant growths, triggered by a chemical attack from gall wasps, midges and mites, fungi and viruses. Many of the invaders are too small to see and lack common names, yet their complex lifestyles are spectacularly interesting.

Oak are among the trees most frequently targeted: galls to look for include forms described as apples, marbles and buttons. Find silk button galls (pictured) on the leaf undersides, like clusters of tiny bagels. Each is a nursery for a gall wasp larva, which overwinters on the fallen dead leaf, then hatches in spring.

Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)

Late summer and autumn are a busy time for bottlenose dolphins. “After a 13-month gestation, the females give birth at the end of August into September,” says Charlie Phillips, a field officer for Whale and Dolphin Conservation based at the Moray Firth on the east coast of Scotland. “Around this time, the dolphins’ main food source here switches from migratory salmon to shoaling mackerel coming in from the North Sea. The females are glad of fish like mackerel and also herring, as they can metabolise the lipids quickly, turning them into thick, rich milk.” Amazingly, the young will suckle for 18 months.

British and Irish waters are home to some of the world’s largest and most northerly bottlenose dolphins. The best-known (and most easily seen) populations are resident in the Moray Firth, Cardigan Bay in Mid Wales, and Galway Bay and the Shannon Estuary on Ireland’s west coast, though there are a few in the Hebrides and south-west England.

In his book The Nature of Summer, naturalist Jim Crumley describes beautifully how pods of dolphins “flirt in equal measure with surface and underwater”. Sometimes, he writes, they swim in an unhurried, almost matter-of-fact style, but it’s the “playing-to-the-gallery high jinks” that wildlife watchers are really after.

Learn more about dolphins:

- River dolphin guide: where they live, the threats they face, and what is being done to save them

- Wildlife Q&A: What do dolphins do during storms?

- Photography Masterclass, with Mark Carwardine: In The Field: A lifetime photographing whales, dolphins and porpoises

Tucuxi river dolphin. © Kike Calvo/Universal Images Group/Getty

Ruff (Philomachus pugnax)

Britain is a wader nation. After all, it has a huge coastline, with a quarter of the estuaries in north-west Europe. That’s a lot of tidal mud – perfect for wading birds. Then there is the country’s position at the intersection of several important avian flyways. The ruff is just one of a dozen or more southbound wader species that pass through between July and October. Research by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) shows that male ruffs will mostly winter in south-west Europe, while the females will head on to Africa.

Footballer hoverfly (Helophilus pendulus)

Even a small garden can attract a variety of bees, butterflies and hoverflies well into September. One handsome hoverfly to lookout for this month is Helophilus pendulus, nickamed the ‘footballer’ for its snazzy stripes (presumably this species, along with hornets, is particularly popular with supporters of Watford FC).

As summer shades into autumn, make sure there is still plenty of nectar for the insects in your garden by including late-flowering plants such as red valerian, common knapweed, sedums, hebe, Verbena bonariensis and certain varieties of buddleia.

Pine marten (Martes martes)

A recent study by Queen’s University Belfast found that pine martens supplement a few key staples (voles usually) with a cornucopia of seasonal treats. In autumn, they go out of their way to feast on rowan berries, blackberries and bilberries.

Nature writer Polly Pullar, in her book A Richness of Martens, says she has watched them “stuffing themselves greedily... their scats are laden with red rowans like a string of crimson beads”. The martens eat so much fruit, perhaps because it’s a rich source of vitamin C, that some goes almost straight through their system.

The scientific name of the pine marten, Martes martes, is an example of a tautonym, where the genus and specific name are the same.

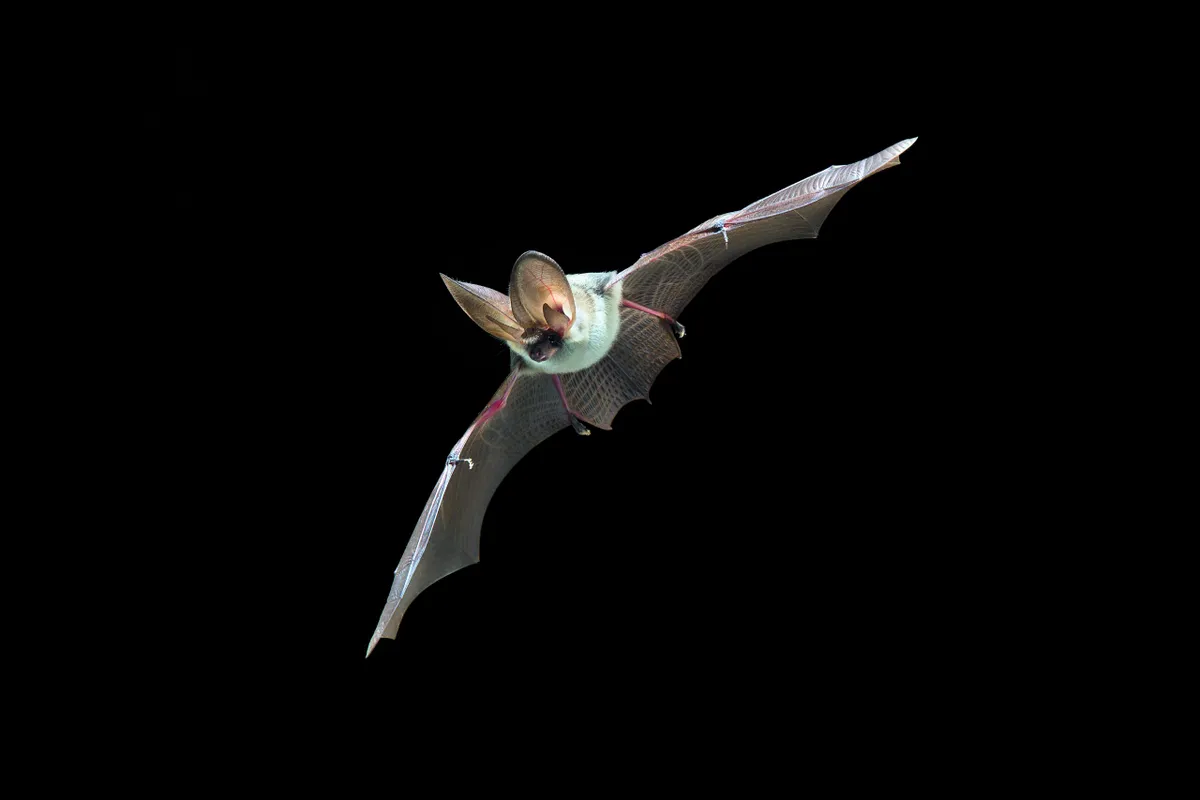

Long-eared bat (Plecotus auritus)

Most British bats have a broadly similar life-cycle. By September, the year’s cohort of youngsters are weaned and out flying, having spent four or maybe five weeks safe in their maternity roosts. It’s now a race to put on weight before hibernation.

Inexperienced bats that become injured, or weak through failure to find enough insect prey, may sadly end up grounded. A grounded bat is extremely vulnerable to domestic cats and other predators. Meanwhile, adult bats are turning their attention to breeding again.

English elm (Ulmus procera)

It’s 50 years since Dutch Elm Disease hit the UK. Until 1970, the English elm was among the most abundant deciduous trees in the lowlands, and a host for many insects, including stag beetle larvae.

Today, mature specimens are few and far between, though Scotland has escaped the worst ravages of the fungus. Brighton is an unlikely urban stronghold. Elsewhere, you’re most likely to find any surviving English elms in hedges, as small saplings or ‘suckers’.

Silver Y moth (Autographa gamma)

Among insects, moths are unsung pollinators. Diurnal species – especially bees – have hogged the headlines. But in the last year, two significant studies by UK universities found that large moths in the ‘macro moth’ group, of which about 800 species are regularly recorded in Britain, are highly efficient pollinators too.

The researchers found many moths with pollen-covered thoraxes, one of the top species being the silver Y. This strongly migratory species arrives in huge numbers from continental Europe, and in September can be seen virtually anywhere.

Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius)

A few birds look somehow too exotic to be truly British. They stop you in your tracks, making passers-by who aren’t already birdwatchers ask: ‘What on earth is that?’ Thrilling encounters like this may even spark a lifelong interest in wildlife. A jay is such a bird.

Though widespread in the British Isles and currently doing well, jays are by far our shyest species of crow, spending much of their time moving quietly among foliage. So, they tend to escape our notice. But all this changes between September and November, when these colourful corvids find their extrovert side. Data from BirdTrack, the interactive recording system run by the British Trust for Ornithology, show that sightings of jays climb rapidly during September, then peak in October, when the species is spotted roughly twice as often.

As late summer turns to autumn, the birds start amassing hoards of acorns and other nuts and seeds to see them through the winter. Not only do they spend longer on the ground foraging, they also make frequent flights to and fro, to bury their treasure, flashing their bright white rumps, and becoming more vocal. The volleys of raucous shrieks earned them the old name ‘screamer of the woods’.

Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa)

It’s not just straight roads and underfloor heating – the Romans are also said to have brought an array of new species to Britannia, including the rabbit, brown hare, carrot, stinging nettle, plum, walnut and sweet chestnut – for making chestnut flour to bake bread.

Sweet chestnut trees (related to beech, not horse chestnuts) don’t bear the autumnal spiny-cased fruit until well into their second decade. But there’s now, as with many introduced trees, renewed doubt about their precise British origins – a new study suggests they didn’t actually arrive until medieval times.

Hazel dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius)

‘Survival of the fattest’ is the modus operandi of many mammals that hibernate, including our native dormice. Weeks of intensive feeding on fruits and seeds leave these small rodents visibly podgy. The fat reserves will see them through a lengthy torpor, usually October to April, during which their body weight falls by a third. To see one, book a place on a ‘nestbox check’ – the one pictured was found during a Wildlife Trust survey. Since dormice are nocturnal and shy, they’re nigh on impossible to spot otherwise.

European hobby (Falco subbuteo)

September is your last chance until next spring to see this Africa-bound bird of prey. Many other raptors are partial migrants (some individuals move while others stay put) but, due to its diet, the hobby is exclusively migratory.

Our most dashing falcon, it specialises in catching dragonflies, swallows, martins and swifts, none of which can usually be found in the UK in winter. Top trivia: the hobby was one of the favourite raptors of inventor Peter Adolph, who in the 1940s borrowed its scientific name subbuteo for his tabletop football game.

Learn more about birds of prey:

Black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa)

Something like 45,000 black-tailed godwits are arriving from the Arctic to winter on our muddy shores, while over 10,000 more pass through en route to West Africa. Until the 1800s, these long-billed waders nested here in sufficient numbers to be harvested as a foodie delicacy. Then they died out as breeders, but recolonised East Anglian fens in the 1950s.

Project Godwit is giving this small population a boost: precious eggs are transferred from wild nests to incubators, then the chicks are released when older and less vulnerable. Look out for the project’s tagged birds.

The scientific name of the black-tailed godwit, Limosa limosa, is an example of a tautonym, where the genus and specific name are the same.

Fairy ring champignon (Marasmius oreades)

Appearing in the grass almost overnight, with seemingly impossible symmetry, fairy rings have been associated with superstition and magic since time immemorial. Confusingly, several abundant species of fungi create these circles, and most are pretty nondescript, with creamy, beige or pale brown caps.

Seen together like this, they remind us that fungi are sustained by huge underground networks of super-fine threads called hyphae. A ring forms when hyphae spread outwards evenly in all directions.

Learn more about mushrooms:

Black darter dragonfly (Sympetrum danae)

Daylight hours are steadily dwindling. By the autumn equinox, which this year falls on 23 September, day and night will be roughly equal. For a sun-loving insect like the black darter, one of our last dragonflies to emerge, this has profound implications.

Not only is the black darter on the wing until well into autumn, but its British distribution is skewed to the cooler, damper north and west due to its preference for shallow peaty pools on moors and bogs. So this small, stocky dragonfly often has to contend with unfavourable weather. The male’s unusually dark coloration serves a vital function: it helps the insect to warm up fast whenever the clouds part.

At night, the black darter rests among reeds or sedges. Photographer Andrew Fusek Peters dreamed of taking a picture of one roosting under a starry sky, but it took “two years of searching” before he finally struck lucky and found a roost site beside a boggy pool on the National Trust’s Long Mynd reserve in Shropshire.

Just after moonset at midnight, Andrew took one exposure to highlight the perched dragonfly, then combined it with a second exposure to capture the magnificence of the Milky Way.

Learn more about dragonflies:

Golden-ringed dragonfly. © Westend61/Getty

Parrot waxcap (Gliophorus psittacina)

Though not as rare as hen’s teeth, a bright green mushroom is nonetheless pretty unusual in the British Isles. Remarkably, the parrot waxcap also has eye-catching blue, yellow and orange forms. It is, says naturalist Peter Marren, “a mushroom of many colours”. For all that, it is petite, reaching only 4cm wide when fully grown. The cap is viscid – that is, it has a slimy coating and feels wet to the touch. Like most other waxcap species, this flamboyant fungus hates fertiliser, preferring the mossy sogginess of unimproved grassland.

By-the-wind sailor (Velella vellela)

Volunteers helping this month’s Great British Beach Clean might find jellyfish-lookalikes known as hydrozoans on the strandline. One found frequently is by-the-wind sailor, which washes up on beaches in large numbers after autumn storms in the south and west.

This creature is an upside-down colony of floating polyps. Stinging tentacles trail behind it underwater, while above the surface there is a transparent ‘sail’ on a purplish- blue ‘raft’. It forms part of the pleustonic community – a varied group of organisms living at the interface between air and seawater.

The scientific name of the by-the-wind sailor, Velella vellela, is an example of a tautonym, where the genus and specific name are the same.

Learn more about coastal wildlife:

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

As opportunist omnivores, foxes don’t waste late summer and early autumn’s fruit bounty. They will happily feast on blackberries or reach up to scrump low-hanging apples, pears and plums.

In September, adults and cubs have both nearly finished growing their new coats for winter, and the juveniles are close to adult size. Competition between young foxes, and between young and adults, can become fierce. The resulting scuffles may be noisy, with rivals chasing one another and squaring up on their hindlegs.

The scientific name of the red fox, Vulpes vulpes, is an example of a tautonym, where the genus and specific name are the same.

Setaceous Hebrew character (Xestia c-nigrum)

There’s an undeniable poetry to moth names. Common species on the wing now, for instance, include the frosted orange, flame carpet, heart and dart, brindled green, merveille du jour and setaceous Hebrew character (pictured), named after the black mark on each forewing that resembles the Hebrew letter nun (נ).

One of around 370 UK species in the huge noctuid family, this moth can be seen throughout the country. If you live in the north you may already have missed it, as there is a single summer generation; elsewhere, a second brood flies until October.

Wryneck (Jynx torquilla)

This small, brown, ant-eating woodpecker dwindled to extinction as a British breeding bird last century. But wrynecks still turn up during spring and autumn migration, especially on the east coast. The British Trust for Ornithology’s BirdTrack website shows a dramatic spike in records in September, when favoured sites such as Yorkshire’s Spurn Point attract the cryptically plumaged migrants en route from Scandinavia to Africa. It has an owl-like ability to swivel its head to look behind it.

Dog rose (Rosa canina)

Rosehips – the flask-shaped, red or orange fruit of the dog rose – were once widely gathered to make tea, syrup and jelly. During World War II, the Ministry of Food even ran a campaign promoting such harvesting to boost Vitamin C levels in a populace deprived of fresh-fruit imports.

Foragers had to be careful of the vicious spikes on dog roses – technically not thorns but prickles. Thorns are modified stems emerging from buds, whereas prickles grow from a plant stem’s outer layer. Small comfort to those who’ve just been pricked.

Learn more about wild plants: